In this photo, which must have been taken at the design studio in Frederiksberggade 28 around 1944-45, can be seen from the left Preben Dorst, Peter Toubro, Allan Johnsen, Bjørn Frank Jensen and Børge Hamberg. This is clearly a situation where one discusses a scene that Dorst is presumably required to draw and animate. He seems to be demonstrating how he intends the character in question to behave. - Photo from the Film Program: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

The feature film "Fyrtøjet":

The daily work continued

Around the turn of the year 1943/44, the feature film "Fyrtøjet" had been in actual production for almost a year, and during that time a large number of scenes had been drawn and animated, just as a considerable number of backgrounds had also been painted. However, when the situation was taken into account, it was clear to the management and the senior executives that at some point it would be necessary to speed up the film's production if the set deadline, which was to premiere around Christmas time 1944, were to be met. But it was also realized that at first it would not be useful to just hire more interpreters as well as ladies for drawing and coloring. The heavy end of all cartoon production is and will be the animation work, and no matter how experienced the animators are individually and as a whole, it always takes a considerable amount of time to key draw the film's characters so that they appear as believable as possible.

It is the highest wish and goal of any 'classical' animator to perform an animation that makes the character or characters for which he or she is responsible so 'alive' and 'well-playing' that the audience immediately and readily accepts the 'play' . Not least because it is important that the animation does not give reason or reason to think about the technique behind. In the illusion number that living images really are, it is important to hide the technique and the 'fif' that has been used to make the number as perfect as possible. As such, it does not concern the audience how many times an animator may have made an animation in order for it to appear and work as intended. As for the key drawing work on "Fyrtøjet", it actually almost never happened that an animation or a scene was remade, simply because time and budget did not allow it, if one would at all hope to be able to meet the set deadline . And this was actually whipped to comply, so that the cash register would not be empty, so that Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S risked going bankrupt with the project.

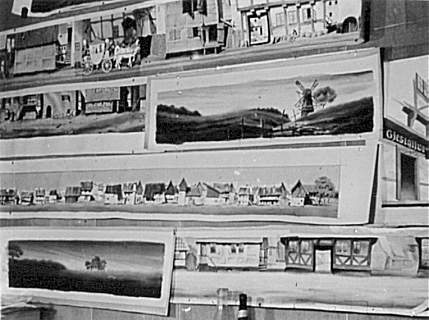

This photo shows a number of different pan backgrounds for the cartoon "Fyrtøjet". However, the background or backgrounds mentioned in the main text are not seen in the picture, as those seen here all belong to a much later sequence in the film. The backgrounds shown above are painted by Otto Jacobsen and Henning Dixner. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

So time was running out, not least because not many scenes with the soldier had been drawn and animated yet, and no scenes with the princess at all. As far as the soldier is concerned, the first step was to have the first scenes drawn with this finished and ready for recording. This was especially true of the scenes where the soldier marches along the country road. The figure was drawn in a repeat on the spot of a total of 12 images, but especially one of the scenes was relatively long, so therefore a pan background of considerable length was required. The scene was even planned in such a way that one would try to create an illusion of perspective depth in the image. Therefore, the background was divided into three 'layers', namely a foreground, a middle ground and a background, each of which had to be moved with its special number of millimeters per. image or exposure.

The foreground, which consisted of a roadside edge with trees about the same distance apart, had to move relatively quickly past in the field of view, and in order not to have to draw and paint a meter-long background, it was arranged and painted in such a way that in principle similarity with the animation of the soldier could be repeated, namely after a panning of a total of approx. 1 meter.

The middle ground, which consisted of the country road itself and trees along the roadside behind, had to 'move' at a speed that suited the soldier's walking movements, ie it had to be moved by a smaller number of millimeters per second. exposure than the foreground. The middle ground could not be 'repeated' during the recording, and it was therefore painted in about 2 meters in length.

The actual background with a hilly landscape with sky and clouds, only just had to be moved approx. 1 millimeter pr. exposure so that it left the impression that the horizon was moving past relatively slowly. This background was therefore only painted in a length of approx. 50 cm.

The management and not least Børge Hamberg would therefore like to see as soon as possible the result of both his animation of the soldier and of Finn Rosenberg's beautiful road background. But since Marius Holdt had enough to do with the recording of especially some of Bjørn Frank's completed scenes, and he was not much to take on the clearly difficult task, they chose to let the scenes with the marching soldier record on the primitive trick table out at Nordisk Films Teknik in Frihavnen. This task was simply left to Børge Hamberg himself to handle, and with me as assistant, we trooped one early morning in the late autumn of 1943 up to Teknikken in Frihavnen. The transport there took place per. tram and on foot. With us, of course, we had first and foremost the scene mentioned above in the form of celluloids with the soldier with us in a cardboard box, and the three slightly rolled-up backgrounds, which are also mentioned above.

At Nordisk Films Teknik, they already had an advanced and modern trick table of model Crass, but it would not be available for the first few days, and we could not wait for that. Therefore, we had to make do with the relatively primitive trick table, which was usually only used for recording title texts, closing texts, fixed signs and pictures etc. The apparatus consisted only of a table with four powerful lamps placed in each corner and with a camera suspended and clamped on a single, square pillar. The camera could only be moved up and down to fixed positions, depending on the size of the material to be photographed. It can therefore be said that the degree of difficulty of the scene that Børge and I were going to record was inversely proportional to the functional possibilities of the interim trick board.

Nevertheless, Børge and I started without delay to prepare for the filming of the decidedly difficult - or perhaps rather difficult - scene. Børge had previously marked two of the three backgrounds involved in the lower edge with the number of millimeter lines and with the distances needed to be able to register these two backgrounds for two arrow marks on each side of the camera field. The third background, the one with the landscape and the horizon, had previously been similarly marked with millimeter lines, but in this case for practical reasons at the top.

The three backgrounds were now placed on the tabletop, and the first celluloid with the soldier placed between the foreground and the middle ground on the dedicated taper rail, which ensures the correct registration of the celluloids in relation to each other. On top of it all, a suitably large, thick and clean glass plate was laid, the purpose of which was to press backgrounds and cells so close together that one could as far as possibly avoid unwanted shadows. Then the camera was set to the correct height and distance so that you could only see the image field that was planned in advance.

Then followed the laborious process of making the actual recording - and this meant further difficulty, for the background had to be recorded in ones, while the soldier had to be recorded in twos, after which the heavy glass plate had to be lifted so that the three backgrounds could again be moved according to the markings. Then the celluloid had to be replaced with a new one, the glass plate put in place again, after which it had to be exposed once and then again the glass plate was lifted and the backgrounds moved the respective number of millimeters needed and then exposed again. Before the following exposure, the same procedure had to be repeated, but this time the celluloid with the soldier also had to be replaced, thus continuing until the scene was recorded finished.

However, Børge Hamberg soon found out that the work of moving the three backgrounds, while at the same time having to change celluloids for every other exposure, was too cumbersome and did not measure up to what was to be achieved with the stage. In addition, there was a great risk that one or more of the backgrounds would 'chop' in the panning, even if we kept control and checked the photo list for each time the backgrounds were moved and exposed. Børge therefore decided to drop the foreground and settle for the middle ground and at the same time let the background horizon stand still. But despite this simplification of the work process, it took us at least two full working days to photograph a scene with a playing time of approx. 6-8 seconds, and then another scene with the marching soldier of roughly the same length of play, but where the soldier was seen in three-quarters profile, where he had previously been seen in profile. In the finished film, the two scenes were each divided into two scenes, with clips of scenes with the flying crow that accompanies the soldier. But with the total working time was of course included a half hour lunch break and a few smaller breaks in between.

Above is one of the two scenes that it caused great difficulty to record on the primitive trick table at Nordisk Films Teknik in Frihavnen. It also ended with Børge Hamberg dropping the front of the three involved backgrounds along the way and settling for the two seen in the picture. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

When the recordings, which were exposed on Agfa film negative, were over, Børge brought the color negative home to the studio. The situation was that color films could not yet be developed and copied in Denmark, neither on 16mm nor 35mm film. The footage of the soldier and of the scenes with the astrologer and the guard, which Marius Holdt had meanwhile also photographed on his trick table, therefore had to be sent to the Agfa laboratories in Berlin, Germany, to be partly developed and partly copied onto positive film. But in order not to risk that the film negative would be present during the transport, Allan Johnsen himself chose to bring it to Berlin. Here he awaited the development and copying, after which he brought both with him home to Copenhagen. After Allan Johnsen's return, the negative film was, as far as I remember, deposited at UFA in Nygade, which had the necessary facilities for storing color film. And it was here at UFA that you had the opportunity to see the working copy.

Unfortunately, the result of Børge’s and my efforts did not turn out well. Not because there was a 'notch' in the panning of the backgrounds, because there was strangely not, but probably as important because it was thought that the soldier's movements were a little too stiff and staccato-like. The immediate consequence of this was, in the first instance, that they temporarily postponed making more scenes with the soldier, because they had actually become unsure whether Børge Hamberg could now also handle the task of drawing and animating the character satisfactorily. He himself had also become insecure because the first scenes he had drawn and animated with the soldier had not turned out as fortunately as both he and the management had hoped and believed. It was therefore agreed that Hamberg should proceed with drawing and animating first and foremost the witch and the crow, figures which immediately seemed easier for him to go to. He had also designed both characters himself, so they were not really difficult for him to draw, but maybe enough to animate. Therefore, he initially went a little cautiously to work with the witch, preferring at first to draw and animate the crow.

The witch and the crow in "Fyrtøjet" were next to the first scenes with the soldier the characters that Børge Hamberg drew and animated individual scenes with. The only in-betweener on the witch and the crow was Harry Rasmussen, who later even key-drawn and animated several scenes with the two characters, but separately. - Drawings: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

One of the first scenes with the crow, which Børge Hamberg animated, was the one where the crow flies away, following the soldier on his way to the big city. But before the soldier reaches that far, it is that he meets the witch, who is standing in front of her large, hollow tree. The crow therefore sits characteristically at the top of the hole into the tree, so to speak, at the 'entrance' to magic and adventure, and here it awaits what will happen next. The crow is probably not part of the fairy tale itself, but it is both literary and symbolically an important figure in the context, as it is an expression of both black magic and death. In part of H.C. Andersen's adventures, there are just such symbolic birds, such as. in the fairy tale "On the Last Day" (1852), in the fairy tale "Anne Lisbeth" (1859) and in "The Gardener and the Lords" (1872). It is therefore fully justifiable and narratively a plus for the cartoon version of the fairy tale "Fyrtøjet" that Peter Toubro and Henning Pade have introduced the crow as a connecting part of the action.

Above is the flying crow, which from the very beginning and approximately to the end of the action in the cartoon "The Lighthouse" largely follows the soldier wherever he goes and stands. The crow was drawn and animated by Børge Hamberg in the beginning of 1943, but later in the production process he handed it over to the then only 15-year-old Harry Rasmussen to key draw the character in some of the film's scenes. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Here the crow is seen for the very first time in the film, where it sits up on a branch and watches the soldier, as he just passes by below. In this scene, Børge Hamberg has used a decidedly cartoon gag, namely that the crow rotates around the branch to be able to see the soldier, so that at some point it hangs upside down. It therefore uses its wings as hands and arms and grabs the branch and pulls itself up again, after which it flies after the soldier. It was me who drew the crow, but for some reason too many intermediate drawings were made, so that the crow unintentionally almost floats out of the picture in slow motion. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

For the time being, Børge Hamberg had more than enough to do with the animation of the crow and the witch, and he also knew that the demanding animation of the soldier lay ahead. That was probably one of the reasons why he soon started giving me decided animation assignments, where I usually also drew the stage myself. Without then knowing about animation concepts such as. "From pose to pose" (from key drawing to key drawing) or "straight ahead" (straight ahead from drawing to drawing), we actually used both methods, but preferably from pose to pose, as the key artist drew nos. 1, 5, 9 , 13, 17, etc. Nr. 3, 7, 11, 15, etc., on the other hand, it was left to intermediaries to draw. Later in the production process, where some intermediate cartoonists had become quite experienced and better understood what animation was all about, the key cartoonists usually left the drawings, which in the English technical language are called "break downs", to these intermediate cartoonists.

The first independent task I got myself with the crow was a scene where you see it sitting up in the tree near the hole and waiting for the witch to haul the soldier up again. The animation was line tested and it turned out to be in order, which is why it was approved. Shortly afterwards, Allan Johnsen came up to the drawing studio, where he immediately went and stood next to me, and as he leaned forward, he said in a low voice: “There is a check for DKK 50 for you over in the office! It's a recognition for the scene you just drew!” Then Johnsen left the drawing studio again. But imagine that he inconvenienced himself over to the drawing studio, just to give me this message! There is probably nothing to say that my self-esteem rose a few degrees, without, however, I was taken aback by my luck.

At that time, I had increased to DKK 75 in weekly salary, a nice salary in relation to what the in-betweeners and the inking and coloring girls got. I do not know exactly what the adult key animators got in weekly pay, but I guess about 125 DKK, and the chief animators a little more, maybe 150 DKK in weekly pay. But a bonus of DKK 50 was in any case very welcome with me, because it gave me the opportunity to buy any of the things I wanted. After my confirmation was over, I had also started paying household money at home, namely DKK 25 a week, so I had DKK 50 for myself. But in return I also had to pay for my personal necessities, such as clothes and shoes etc., which I only considered reasonable.

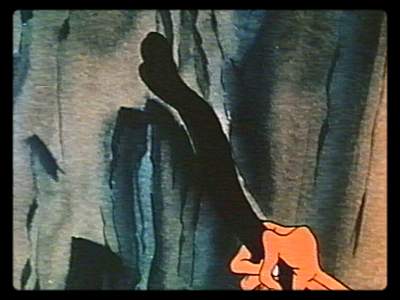

One of my first independent animation assignments, was a scene where the crow sits up in the tree near the hole and watches what the soldier is doing. Børge Hamberg allowed me to both draw and animate the crow, and I was naturally proud and happy about that. My animation was line tested and approved with acclamation, and I was awarded a bonus of DKK 50. However, this first independent animation assignment was only a small beginning in relation to what followed. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Soon after, Børge Hamberg also started drawing and animating the witch, and he started with one of the scenes where the soldier has stopped in front of the witch and her hollow tree. Here he could even draw and animate the soldier on the same occasion, because he stands still and looks up at the witch. Then followed other scenes with the witch, where this is seen alone in the picture, such as. as she explains to the soldier that the large tree is quite hollow inside. During this line, an intercepted scene occurs, where you see the witch's hand pointing at the tree with her knot stick. This scene left Hamberg to me to draw and animate. To the soldier's question about what to do down in the hollow tree, the witch promptly answers: "Get money!"

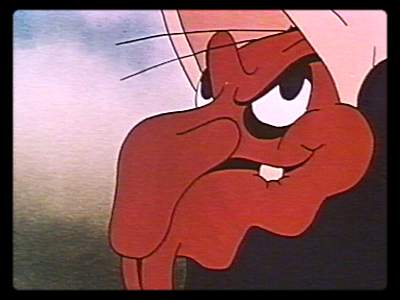

In this scene from the film "Fyrtøjet", the witch is seen in dialogue with the soldier, who on his way to the big city has just stopped in front of the big tree by the roadside. The witch offers the soldier as much money as he wants if he, in turn, wants to crawl into the hollow tree and retrieve the lighter that her old grandmother forgot when she was last down there. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S

In this film image, the witch's hand is seen pointing with the knot stick at the tree, as she (off-screen) says: "Can you see the big tree here! It's quite hollow inside! ” - This so far simple contribution scene, Børge Hamberg left it to me to draw and animate. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Above is a glorious close-up of the witch, as she answers the soldier's question about what he should do down in the hollow tree: "Get money!" It was one of the more characterful and successful scenes with the witch, Børge Hamberg drew and animated. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

When the soldier asks the witch what he should do for her in return for the large amount of money she will actually give him, she laughs and replies: "I do not want a penny!" But you must get me an old Fyrtøj, which my grandmother forgot the last time she was down there! ”

Here is a glorious half-total of the witch, who laughs and defiantly answers the soldier to his question about what she wants in return for the much money she will give him. Here, too, the witch is characterfully drawn and animated by Børge Hamberg. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

A little later, when the soldier is ready to climb up into the hollow tree, the witch says to him: "Now I must tie you a knot around your waist so I can hoist you up again!" Then follows a scene in which the witch is seen tying a rope around the soldier's waist and tightening it. Børge Hamberg also left this scene to me to draw and animate, and it became acceptable, although of course it could have been both better drawn and animated than I was able to as a 15-year-old.

Here is another scene with the

witch, which Børge Hamberg left to me to both draw and animate, and of course I

did my best, but was not entirely satisfied with the final result when I saw

the test film. However, the scene was approved without comment. - Photo from

the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Then

followed some scenes with the witch alone in the picture, which Hamberg drew

and animated and which I drew. Among other things. one where the witch shouts

to the soldier down in the tree: "Do you have the Fyrtøj with you !?"

The witch shouts to the

soldier down in the hollow tree: "Do you have the lighter !?" This is

one of those scenes that is cross-cut from time to time to see what the soldier

is doing down in the hollow tree. Animation: Børge Hamberg. Intermediate

drawing: Harry Rasmussen. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

To the witch's question, the soldier answers: “No, I had almost forgotten that!

But now I have to pick it up! ” After which he goes back to the cave to

pick up the lighter, which is left in a niche where it is in a leather purse.

Then you see a close up of the soldier's hand reaching in and taking the purse

with him. I was allowed to draw and animate this scene, especially because

Børge Hamberg had found out that I was good at drawing hands. However, it was

not until the autumn of 1944 that I made the scene, but for the sake of

context, a picture from it is shown here.

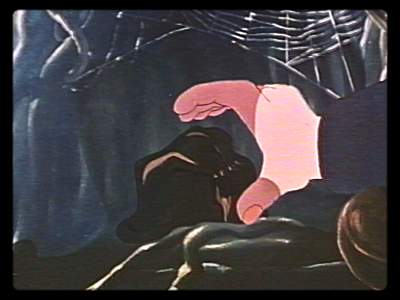

In this photo from the film,

the soldier's hand is seen reaching for the leather purse with the lighter,

which he initially forgot he had to bring up to the witch in return for the

large amount of money she has given him. The hand and the leather purse are

designed and animated by Harry Rasmussen. - Photo from the film: © 1946

Palladium A/S.

When

the soldier has come up from the tree again and has the fyrtøj with him, he

asks the witch what she wants with the old lighthouse. It does not come to him,

she replies angrily, to which he threatens to cut off her head if she does not

want to answer his questions. As she continues to refuse, the soldier pulls out

his saber and automatically chops off the head of the basically caseless and

defenseless witch.

In this close-up of the witch,

she refuses to answer the soldier's question about what to do with the old

lighter. The stage was left to me to draw and animate, but even I do not really

think I managed to draw the witch, so she looked exactly like the witch that

Hamberg drew. However, he was very well pleased with my efforts. - Photo for

the film: © Palladium A/S.

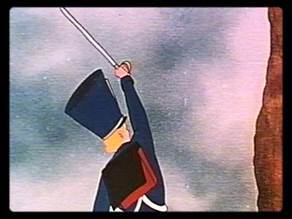

Half-close by the soldier, who

has pulled and raised his saber, ready to chop off the head of the basically

pointless witch. There is very little animation in this scene, with the soldier

anticipating his blow. but the soldier still seems ‘alive’ and present. The

scene was drawn by Mogens Mogensen, - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S

Half-close to the witch, who

seeks to defend herself, to avoid the soldier's saber, but in vain. But you do

not see directly that he chops off her head, it is only heard on the music,

which is very dramatic at this point in the film. Also in this scene there is

not much animation, but only the hint of a movement, as the witch has lifted

one arm and as it were stretches the ward away. The scene was drawn by Harry

Rasmussen. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

One of the scenes in the sequence was the crow in close-up, where one sees its violent reaction to the soldier chopping off the witch's head. This scene was one of the first and most successful animations I made in "The Lighthouse". After my animation of the crow had been line tested and approved, this time with flying colors, Johnsen came over again and stood next to me and said in a low voice: “Your scene with the crow was good! Go over to the office and pick up a bonus check for DKK 90, which is waiting for you! ” I was sincerely surprised by the generosity that the management showed me again, and I was completely shy about the situation, so I only managed to come up with a well-meaning "Thank you!".

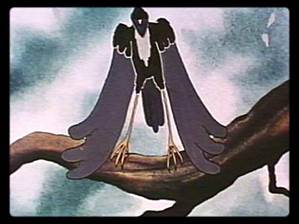

Here

follows the scene with the collar's reaction to the soldier chopping off the

witch's head, which I drew and animated, and which brought me a bonus of DKK

90.

The animation of the crow is

in my own opinion - and also others' - one of the most successful scenes I

contributed to in the feature film "Fyrtøjet". The scene was drawn in

1944, when I was just 15 years old. But even today, the animation seems fairly

professional and acceptable. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Here the severed head of the

witch is seen lying at the root of the tree, while the soldier, unaffected by

his misdeed, sticks his saber back into the vagina. But H.C. Andersen's side

has put the symbolic in the action, that the 'hero' frees himself from

superstition and the black magic, and this is probably how one should perceive

the fairy tale "The Firecracker". The scene is drawn by Mogens

Mogensen. - Photo from the movie: © 1946 Palladium.

DKK 90 was a lot of money at the time, and they were actually used 'sensibly', because I thought I owed my parents a gratitude for their great patience with me, who over the years had so stubbornly insisted that it was cartoons, and only cartoons I would make when I grew up. But that is why I chose to use the money as a payout on a TO-R console radio with a built-in gramophone and automatic disc change. It made mom, dad and my younger siblings very happy, and my parents had it for many years after, and especially mom used the turntable diligently. She especially loved dance music, which was understandable considering she was a dance teacher. By the way, I also used the gramophone after the war, where I started collecting classical music and swing records with i.a. Benny Goodman.

A

mention of the many scenes that take place down in the witch's hollow tree,

where the three dogs live in separate chambers and guard the coffin with copper

money, the coffin with silver coins and the coffin with gold coins, has been

deliberately omitted here. Simply because they had not yet been drawn and

animated at the time in the production process we have reached here. These

scenes were first drawn and animated later, when Hamberg had again gone over to

drawing and animating the soldier. It is often the case - or at least that was

the case with "Fyrtøjet" - that the film's scenes are not necessarily

made in action or chronological order. It is usually found most practical for

an animator to draw and animate scenes with the same or possibly the same

characters and backgrounds, even if the scenes are far apart in the film,

because you can thereby take advantage of the routine that the animator

gradually acquires.

The king, the queen and the courtiers

In the following, we will take a closer look at the animation tasks that Bjørn Frank Jensen was responsible for, and there were actually not so few. In addition to the astrologer and the guard, he drew and animated the royal majesties and virtually all members of the service staff attached to the court. In addition, the members of the government and the writers, as well as the royal. lifeguard.

Some of the characters that Bjørn Frank began to draw and animate while he was

still working in the drawing room at Frederiksberggade 28 were the king and

queen, and one of the first scenes with these was the one in which the angry

astrologer in the middle of the night ran up to the castle, where he bursts

right into the royal bedroom and awakens both majesties by slipping into the

king's slippers and falling over the bed.

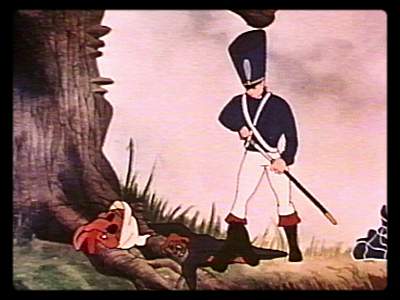

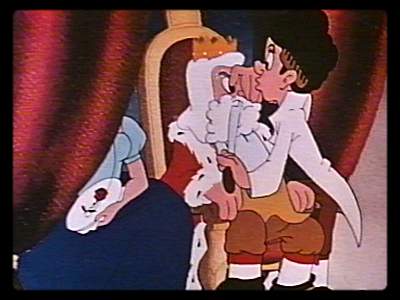

Here is the scene where the

astrologer has run at a breakneck pace from the Round Tower and up to the

castle, where he bursts right into the royal bedroom and slips into the king's

slippers, which stand next to his bed. In this unusual and clumsy way, the king

and queen are awakened, only to hear the alarming news that the astrologer has

interpreted the stars in such a way that they predict that the princess will

marry a simple soldier. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Here the astrologer tells the

king and queen that their daughter will marry a simple soldier, which of course

worries the majesties, who have never before been out for anything like this in

their otherwise so good, calm and safe everyday life. - Photo from the film: ©

1946 Palladium A/S.

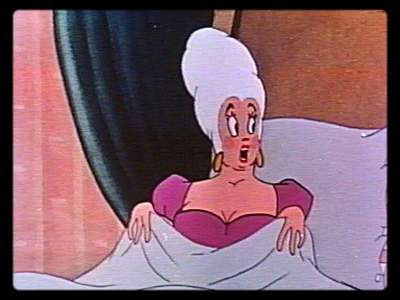

The good queen is seen here

just before she faints with astonishment at hearing the astrologer's account of

what fate is predicted that their dear daughter will have if everything goes as

the stars predict. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Among

some of the first scenes that Bjørn Frank Jensen drew and animated, I

especially remember his animation of a scene with the king. It was the scene in

which the king, wearing a dressing gown and slippers, hurries back and forth in

the dining room, all the while mumbling that it is a terrible story. It happens

after the princess has told him and the queen about a dream she had had that

night, in which she dreamed that a big dog came and brought her to the soldier

who kissed her, after which it brought her back to the castle again . This is

probably a repeat, but with quite a few drawings. However, it was impressive

and inspiring for me to observe how thoroughly Bjørn Frank drew himself to the

result, sketching every single key drawing vigorously, until he thought he had

found the best action-line and best pose for each and every drawing. Bjørn then

interest-plotted his own key drawings, which were then left to Helge Hau to

draw. Once that was done, the animation was line tested and approved, and could

then proceed to drawing and coloring.

Here the king is seen, wearing

a dressing gown and slippers, trotting back and forth in the dining room, upset

over the dream the princess has told about at the breakfast table, namely that

she dreamed that a dog came and fetched her to a soldier, and that it then

brought her home to the castle again. The King is drawn and animated in Bjørn

Frank Jensen's well-known line, which was characterized by his enthusiasm for

and inspiration from American cartoons, especially Disney cartoons. - Photo

from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

However, Bjørn Frank had to skip a number of scenes in which the princess

appears, simply because there was not yet a final design of this significant

figure, and no animation of her at all. He therefore had to go on to draw and

animate scenes in a completely different and following sequence, namely the one

where the king sits on his throne and has to take a stand on the daily affairs

of the court and the government. Below, the chef of the court comes pulling the

cook boy by the ear, to present to the king that the cook boy has had his

fingers in the jam jar, which makes the hard-of-hearing old man for the writers

ask: "What's he got?" - "He has had his fingers in the jam

jar!" answers one of the writers. "Oh, that poor thing!"

exclaims the old man, "Is his finger broken!" After which everyone laughs.

"Take him out!" commands the king and adds: "He must be beaten

on the stomach!"

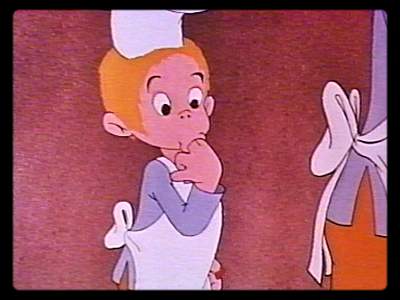

The chef boy has committed a

crime by licking the jam jar, and therefore the chef wants the king to decide

what to do with the apprentice. Here the chef comes pulling with the cook boy

by the ear, on his way to the king's throne. - Photo from the film: © 1946

Palladium A/S.

Half total of the chef boy,

who untouched by the situation continues to lick his fingers. The figure is a

characteristic example of Bjørn Frank's drawing and animation style. - Photo

from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

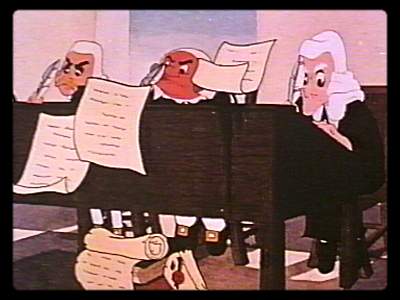

Here are the three writers who

write down everything that is said during the audience. The stage is designed and

animated by Bjørn Frank Jensen and is part of a longer sequence during which

the king is presented with the court's daily problems. - Photo from the film: ©

1946 Palladium A/S.

Here the kingdom's finance

minister arrives with a giant roll of paper under his arm. The character is at

once comical and touching in his movements, which are well drawn and no less

well animated. Again a fine example of Bjørn Frank's abilities as a draftsman

and animator. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

However, the time has apparently also come for the Minister of Finance to

submit accounts for the kingdom's finances. For that purpose, the very small

man has brought with him a long list of accounts, which he reads out in a

drive, without anyone noticing him, the king in the least. Below, the royal

barber arrives to shave His Majesty, and the king asks if there is anything new

in the city, to which the barber replies that it is not there - yes, by the

way, a soldier has arrived in the city, who turns around with money. It

naturally frightens the king to hear that it is a soldier, but before he can

think any more about that matter, he is interrupted by what is happening right

around him.

The royal barber is seen here

in the process of the king's morning shave. When the king asks for news from

the city, the barber can tell that a soldier has come to the city, who is

obviously rich, because he strikes with money. This, of course, frightens the

king, who, however, will have to continue the audience. Both characters are

drawn and animated by Bjørn Frank Jensen. - Photo from the film: © 1946

Palladium A/S.

The three scribes have more

than enough to do with writing down everything that is said during the king's

morning shave and the audience of the court people. The sheets of paper fly

quickly around the ears of the writers, who strive to keep up with the high

pace at which the Minister of Finance in particular speaks. - Photo from the

film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

On the

whole, Bjørn Frank Jensen drew and animated a large number of scenes while he

was still working on the drawing room in Frederiksberggade 28. Among these were

also some scenes with the soldiers, as led by the queen, the court lady and the

three lackeys, going out into the city and takes place the place where the

soldier lodges and where the court lady has put a cross on the gate, in order

to be able to recognize the place again. However, it turns out that virtually

all doors and gates have been ticked, which is why the search for the soldier

is in vain this time around. But again, Bjørn Frank showed his great efficiency

and skill as a draftsman and animator, and equally well and thoroughly for

every single scene he was responsible for. The same applied to his

intermediaries, first and foremost Helge Hau, but e.g. also Bodil Rønnow, who

occasionally got one of Bjørn Frank's scenes for intermediate drawing.

Here is the scene in which the

court lady, after finding the soldier's abode, namely at the inn, very

cunningly strikes a large cross at the gate, so that she will be able to

recognize the place again. This she informs the king and queen, who immediately

orders an entourage consisting of the three lackeys and a company of soldiers,

to accompany him and her to the inn, where the presumptuous soldier is to be

arrested. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

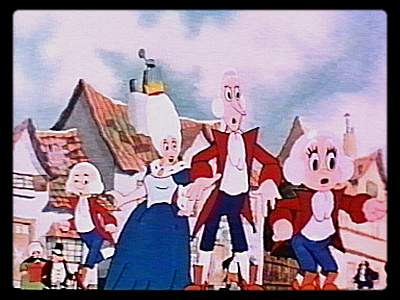

Here the king and queen and

their attendants are seen on their way to the inn, where the soldiers are

supposed to arrest the soldier so that he can be brought before a judge and get

his deserved punishment for having violated the king and queen's order that he

did not have to contact the princess. He has violated this command by using the

magic fire and its one 'spirit', namely the smallest of the three dogs, which

has both fetched the sleeping princess to the soldier and brought her back to

the castle again. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

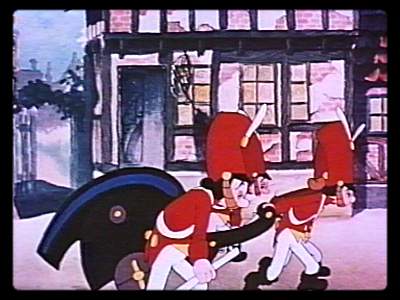

Here, for safety's sake, the

soldiers have driven the cannon into position in front of the inn, to arrest

the soldier and lead him to the courthouse. The characters are drawn and

animated by Bjørn Frank Jensen, just as the backgrounds throughout the sequence

are painted by Finn Rosenberg. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

The little soldier here

prepares the cannon for firing if necessary. Bjørn Frank added a gag with the

soldier dropping the heavy cannonball down over one of his comrades' feet, so

that he jumps around in pain. It was thought that it would seem funny, whatever

it did to the audience, who laughed at the situation. The kind of gags about

letting it go beyond ‘authorities’, the cinema audience also knew from e.g.

some of Disney's cartoons and not least from Chaplin's vagabond movie. - Photo

from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Here, one of the lackeys has

noticed that there are also signs at other gates in the area, and thus the

whole situation has actually changed to the great disappointment of the king,

queen, court lady and the soldiers, who had all hoped that now was it was only

a matter of minutes before the soldier was taken into custody. - Photo from the

film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

The great disappointment and

defeat characterizes everyone's faces, as one is forced to acknowledge that the

action has been in vain and that one must return to the castle with a negative

result. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Here the king lets his anger

and frustration spill over to the little soldier, whom he commands to follow

suit with his comrades. The soldier, of course, immediately obeys the king's

command. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Some of the scenes that Bjørn Frank Jensen drew and animated while he was still working at the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28, were the ones in which the princess is either mentioned or appears. It happens immediately after the astrologer has awkwardly awakened both the king and the queen, which happens in a scene that Bjørn Frank actually first drew and animated later in the production process. But so far he could draw and animate some of these scenes, even if the princess appears in it, but she would be able to draw in later.

At

this point in the film's plot, it happens that in an attempt to prevent the

princess from coming into contact with the soldier, the king orders that she be

led up to a tower room, which must be guarded around the clock by a court lady,

and which only the royal family has access to. Here Bjørn Frank drew and

animated a scene in which the three lackeys, led by the king, carry the bed

with the sleeping princess along the castle corridor on the way to the tower.

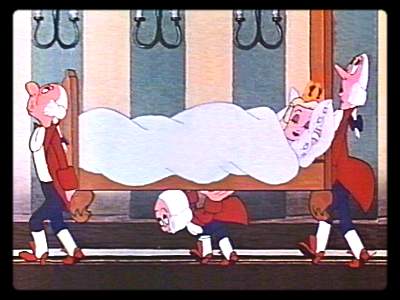

Here the three lackeys carry

the bed with the sleeping princess, whom the king has ordered to be locked

inside a tower room, to prevent the soldier from possibly coming into contact

with her. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Then Bjørn Frank drew and animated a scene in which the three lackeys, still

led by the king, carry the bed with the sleeping princess up the tower stairs.

The very special thing about this scene was and is that due to the light from

the hung torches, it is the shadows on the tower wall that first appear and

like moving in front of the actual persons. It is a surprisingly good effect,

which, incidentally, had been suggested by Mik. With this scene and the

sequence in which it is included, you might get an impression of what Mik's

possible instruction of "Fyrtøjet" could possibly have brought with

it of professional quality for the film. On the other hand, Mik’s - as little

as Myller’s - own animation style would hardly have meant a win.

Here is one of the most

graphically effective scenes in "The Lighthouse", namely the one where

the three lackeys led by the king carry the bed with the sleeping princess up

the tower stairs on the way to the room where the princess is to be locked in

and kept under constant observation by a reliable court lady. The special

effect consists in the fact that the persons cast shadows on the tower wall.

The stage was laid out, drawn and animated by Bjørn Frank Jensen on the basis

of Mik's sketch proposal. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A / S.

More about the animation of the soldier

It has been mentioned and mentioned several times that it was originally intended to engage Jørgen Müller and Henning Dahl-Mikkelsen (Mik) as so-called directing animators, i.e. as supervisors of the animation work, but as previously described, the parties apparently could not agree on the working conditions. As mentioned, Müller and Mik thought that a so-called storyboard should be made, in which the course of the film was depicted more or less outlined, scene by scene and sequence by sequence. This working method, which helps to provide a visual overview of the film's action sequence, sequence by sequence and scene by scene, was used with great efficiency by e.g. Disney, where the method of storyboarding had also been invented and developed. It can be said that a storyboard in principle actually resembles the well-known continuous cartoon, but despite the obviousness of this method, it still took several years before it was used in connection with cartoons in Denmark. Nowadays, the preparation of a storyboard is considered standard procedure that no responsible producer or cartoonist would dream of doing without. In the last couple of decades, it is not uncommon for American film directors in particular to even have storyboards made for their live action feature films.

However, Allan Johnsen was of the - probably erroneous - view that the method would prolong and increase the cost of production, and since Müller and Mik did not want to do without a storyboard to manage the project, nothing came of the intended collaboration. There is also an unconfirmed report that Müller and Mik demanded wages that exceeded what Johnsen and his board had intended to pay. Incidentally, it is a big question whether the film would have been better directed and animated if the two experienced cartoon directors and ditto animators had been given the opportunity to direct the "Fyrtøjet" and supervise the animation for the film. The answer, in my personal opinion, must be that it would probably have meant in more ways a more professional 'cartoon instruction' and a much more 'fluent' and flawless animation, but at the same time I think that the originality that despite the approaches to the Disney animation is still in the film, would have been lost in Müller and Mik's instruction and favorite "rubbery" animation style. This assumption and assessment is based on the fact that Mik was called in for a while during the production process to make a test animation of a single scene. It was about the scene in which the soldier is introduced, that is, where you see the main character for the very first time in the film, as he appears behind a hill that the country road runs across, and moves towards the foreground, where a single butterfly and some small birds fluttering around.

When Mik

came up to the drawing studio a few days later and handed in his sketch

animation, both the management and the animators all largely agreed that Mik's

version of the soldier was too soft and 'rubbery' in the movements, so the

character totally lost his character of credible 'hero figure'. But Mik's

animation would not have been a problem if the soldier had been a slightly more

grotesque and comical character, as was the case, for example, in Müller and

Mik's own cartoon version of "Fyrtøjet" from 1934, and to partly also

in the cartoonist Richard Møller's cartoon version of the fairy tale

"Fyrtøjet". But the soldier in the feature film "Fyrtøjet"

was conceived and designed à la the prince in "Snow White" or Prince

David in "Gulliver's Journey", which you can partly be convinced of

by looking at Børge Hamberg's earliest draft of the soldier.

Here is the scene to which Mik

made a discarded test animation of the soldier. Here is Børge Hamberg's

character version of the soldier, which you can see on the way up the hill. The

Butterfly and the Little Birds are designed and animated by Preben Dorst. The

background is here, as in the previously shown photos from "Fyrtøjet"

all painted by Finn Rosenberg. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

The short of the long is therefore that the management and the animators agreed that Børge Hamberg's character and animation of this would be more 'real' for a feature film like "Fyrtøjet", than e.g. Mik’s design and animation of the same character. It was therefore decided that Børge Hamberg should continue to draw and animate the soldier in the rest of the scenes in which he appeared, or at least supervise the animation, if another or possibly more animators were assigned some of these scenes for time reasons. This quickly turned out to be the case, to which I shall return. Incidentally, Børge Hamberg himself thought that he would probably succeed in making the soldier more 'alive' and 'human-like', as he got to draw and animate himself into the figure. Several of the following scenes with the soldier, which Hamberg drew and animated, showed that he was right in this assumption. In the film, there are several scenes with the soldier, where the character drawing and animation are on a par with some of the best that has ever been made of serious animation freehand in cartoons, and thus without the use of rotoscopy. And the soldier in "Fyrtøjet" is in my opinion significantly better animated in these scenes, to which we must return, than e.g. the prince is in "Snow White" and Prince David in "Gulliver's Journey".

As previously mentioned, Bjørn Frank Jensen has stated that at the above-mentioned time, when he did an animation test on the soldier, he was also asked to look at the script because he felt a little insecure at the beginning. The script followed Andersen's adventures quite closely and therefore began with the soldier marching along the country road. Mik suggested that the film should instead start with the astrologer at Rundetårn, who sees in the stars that the princess should marry a simple soldier. This upset the astrologer that immediately informs the royal couple at night, and the further action therefore leads to the king ordering that the sleeping princess be immediately led up into one of the castle’s towers and there be guarded by a court lady. Only the next day do we see for the first time the soldier, who on his way into the capital meets the witch and what follows. According to Bjørn Frank, Mik even made layouts for the opening scenes, for which Bjørn then made the animation. But strangely, Mik got no credit on the subtitles of "Fyrtøjet" for this significant contribution to making the film better.

But

here it must be repeated that, despite Allan Johnsen's well-meaning motives, it

must probably be regarded as a fatal mistake and shortcoming that

"Fyrtøjet" was not made on the basis of a visualized course of

action, i.e. on the basis of a storyboard, not to mention a so-called

story-reel. The latter has always been the standard procedure at Disney, and in

recent times it has also become so in virtually all international cartoon

production. In recent times, however, the procedure was only used as a standard

procedure in Danish cartoon production from and including Jannik Hastrup's

feature film "Samson & Sally" (1984), whereas a

"story reel" was first made the standard procedure from Swan

Production's production of the feature film "Valhalla" (1986).

But as mentioned, it was not possible for either Finn Rosenberg, Børge Hamberg

or Bjørn Frank Jensen to convince Johnsen that at least a storyboard was in

fact an almost indispensable tool, a bit in the direction of what a detailed

budget and planning overview is for the financing and production of a similarly

large project of any kind.

This photo shows three of the

leading key cartoonists on "Fyrtøjet": From left Børge Hamberg,

Preben Dorst and Bjørn Frank Jensen, who here confer with each other on the

organization of a scene. The three cartoonists and animators acted

simultaneously as sequence instructors, partly on their own sequences and

partly on sequences that involved all three parties. - Photo from the Film Program:

© 1946 Palladium A/S.

A misjudgment - and untrue allegations

The only ones who from the beginning had a fairly comprehensive overview of the film "Fyrtøjet"'s plot were Peter Toubro, who had the main responsibility for the script, and then Finn Rosenberg and Allan Johnsen, who all enthusiastically supported the case. However, Johnsen was hampered by his total lack of experience with films in general and cartoons in particular, and by the fact that he constantly had to keep the economy and budget compliance in mind. But it was in practice Peter Toubro who, in a sense, became the film's actual director. However, he collaborated or conferred in the daily practice with Finn Rosenberg, Børge Hamberg and Bjørn Frank Jensen, as he probably must have acknowledged that especially the latter two were experienced animators who essentially knew how to make cartoons. Toubro himself, like Johnsen, lacked virtually any prerequisite for making cartoons, let alone being a director of such, and even a long cartoon.

In Tegnefilmens historie, Forlaget Stavnsager 1984, pages 103-04, the author, editor and cartoon enthusiast Jakob Stegelmann is unfortunately guilty of passing on some incorrect information during the mention of "Fyrtøjet". He writes about this, among other things:

"Not a single of the cartoonists knew anything about animation beyond what they had been able to study in the cinemas. Not a single one of the cartoonists and colorists had tried it before, and none of the leading artists and administrators knew what a great project they had thrown. out in.

The production therefore did not escape chaos, as a multitude of people during the four years were employed at all levels of film production. The drawings and coloring were done around Copenhagen, and there were no fixed rules for who made what and when. In other words, there was no higher goal. There was not even a manuscript to go after."

There can be little doubt that Jakob Stegelmann has taken his impression of and his "knowledge" about the production of "Fyrtøjet" from i.a. interviewed by Børge Ring in Carl Barks & Co. No. 17, 1982, and from the interview with Kaj Pindal in Carl Barks & Co. no. 18, 1983. Børge Ring was not an employee of "Fyrtøjet", and can therefore, for good reasons, have no first-hand impression or any exact knowledge of the film's making. Although Kaj Pindal for a time worked as an in-betweener on the film, his impression of the production conditions and conditions under which he was created is unfortunately not entirely in accordance with the actual conditions. Which there is nothing to say, because he sat with Ib Steinaa out in the drawing studio, which the company in 1944 had arranged above Nørrebro's Messe on the corner of Nørrebrogade and Blågårdsgade. Here they worked as in-betweening cartoonists mainly for Bjørn Frank Jensen, who was also the head of the drawing studio on site, and who was usually a silent and enclosed man, who also probably thought that the film's screenplay etc. did not apply to the ‘slaves’.

But first, it is incorrect that "not a single one of the cartoonists knew anything about animation beyond what they had been able to study in the cinemas." Børge Hamberg as well as Bjørn Frank Jensen, Kjeld Simonsen, Erik Christensen and Erik Rus, had learned what animation is all about, partly from Müller and Mik at VEPRO, and for Hamberg’s, Erik Rus' and Erik Christensen and a few other artists also at Hans Held in Germany. In addition, Erik Rus and Børge Hamberg had experience from their production of the short entertainment cartoon about "Peter Pep and shoemaker Lace-up boot" (1940). Secondly, there were no definite interest draftsmen on "Fyrtøjet", but on the other hand inkers and colorists, and quite a few of these had previously been employed partly by Jørgen Müller at Gutenberghus and partly at VEPRO. Thirdly, the "leading artists" knew very well what a huge task they had undertaken, but it is probably true that the "administrators", who probably here primarily say Johnsen and Toubro, for good reasons had not been aware of it in advance .

Fourth, there was at no time any "chaos, as a multitude of people during the four years were employed at all levels of film production." Except that you can probably not call approx. 200 people for "a multitude of people", and that the majority of these people were 'only' employed on "Fyrtøjet" for about two years, on the contrary, it was determined from the very beginning of the production which people did what and when.

As for Jakob Stegelmann's claim that there was no "higher goal" for the project, it must be rejected that all the involved and deeply committed animators, cartoonists and administrators were involved in making such a good cartoon as it was at all could be done under the given conditions and conditions. And everyone hoped and reckoned that "Fyrtøjet" would be such a big success that the production could be continued with new long as well as short H.C. Andersen fairy tale cartoons. In the spring of 1944, there were also advanced plans to continue production after "Fyrtøjet" with a series of short H.C. Andersen fairy-tale cartoons, i.a. based on fairy tales such as "Klods-Hans", "What Father does ...", Elverhøj "," The Princess on the Pea "and "The Emperor's New Clothes", but due to the fact that the production of "Fyrtøjet" dragged out and cost significantly more than expected, and that one also had to involve a co-producer, namely Palladium A/S, nothing came of the plans. It did not do so until 1948, when Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S again became involved in a feature film project, this time based on H.C. Andersen's fairy tale "Klods-Hans".

But completely erroneous is Jakob Stegelmann's claim that "there was not even a manuscript to go by." The fact is that even before the actual production started, there was an even very detailed script, which was prepared by mag.art. Peter Toubro with expert assistance of mag.art. Henning Pade, and with Finn Rosenberg and Allan Johnsen as "sparring partners". And if nothing else, I can personally witness the existence of such a screenplay, because I have both seen and had it in my hands during my close collaboration with Børge Hamberg during the two years I was employed by Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S. But what has become of the copies of the screenplay for "Fyrtøjet", which existed at the time, I have no knowledge of, but probably a copy of the screenplay for "Fyrtøjet" is kept at Palladium A/S and possibly also one at the Film Museum.

However,

with the present and relatively detailed first-hand description of the

circumstances, conditions, and conditions under which the feature-length film

"Fyrtøjet" came to be, I hope to have helped to conjure up at least

some of the pending incorrect perceptions, claims, and myths surrounding the

film.

"I feel like the bird in the cage…"

But we will now return to the description of how the daily work took place on "Fyrtøjet", and wait with the further mention of Børge Hamberg's animation of the soldier and two of the three dogs. The situation is that dog no. 2, the one who guards the coffin with silver money, does not play a big role until the end of the film, where it especially helps the largest of the dogs to punish the authorities who have wanted to hang the soldier. And in the final scenes, all three dogs for a change were actually drawn and animated by Kjeld Simonsen (Simon), which I will return to in chronological order.

In the meantime, as I said, we must return to the film's heroine ', the beautiful princess, who so far only existed on a character draft by Børge Hamberg. But as previously mentioned, the management and the chief cartoonists had problems finding a suitable cartoonist and animator who would and could take on the demanding task of drawing and especially animating the princess. However, it had been realized that it would not be possible to get a cartoonist and animator 'from outside' who would take on or be able to handle the decidedly demanding task. Therefore, one had to look around in one's own ranks for a cartoonist and animator who one thought would be best suited to design and key draw the princess. At first glance, one would think that a female cartoonist and animator would have been the natural choice for the task. But at the time, it was quite unusual for female key cartoonists, as animation by tradition and automaticity was considered a distinctly male job. However, there was the possibility that e.g. could have chosen Bodil Rønnow, who was a good illustrator, but who primarily worked as an in-betweener illustrator, and otherwise had no experience with animation, which she could possibly have learned. But when asked if the job would possibly be something for her to take on, she answered evasively due to her own great personal insecurity, referring precisely to the fact that she had no experience as an animator at all. Thus, in a way, this obvious possibility was ruled out.

Back there were not so many people to choose from, because the few leading key cartoonists had long ago been assigned the character or characters that it was immediately thought that the person or characters in question would be suitable for drawing and animating. The choice therefore soon fell on Preben Dorst as the most obvious subject, as at that time he had only animated scenes in scattered fencing and had not yet been assigned an independent task with a main character. In addition, he had a slightly neat but sensitive drawing style, which in principle would be suitable for just a figure of a character like the princess.

However, faced with the question of drawing and animating the princess, Dorst understandably had great concerns about possibly having to take on the task, which he rightly found difficult, especially because he was not yet fully experienced as an animator. However, there was no way around it, and under a mixture of decoys and a certain amount of pressure, he therefore had to embark on the very demanding and difficult project, first by designing the princess figure, which he set as a condition, and then gradually by try to animate and breathe life into her. The latter was the most difficult, because Dorst - by the way, like the other animators - did not even have a recorded audio tape to refer to. Such a thing would probably otherwise have been able to help Dorst draw the right key positions and movements and time them so that they fit as well as possible to the actor's voice that was to imitate the princess.

But

Dorst then - somewhat hesitantly - began to sketch out how he himself thought

the princess figure should look like. During this work, there were also some of

the studio's other artists, such as the middle characters Erling Bentsen and

Bodil Rønnow, who each gave their take on the princess' figure and appearance.

To the left is Erling

Bentsen's proposal for what the princess in "Fyrtøjet" should look

like. However, the proposal was not adopted. - Drawing: © 1943-44 Erling

Bentsen v / Aase Ekstein. To the right is Bodil Rønnow's bid for the princess'

figure and appearance, which, however, was to some extent inspired by Preben

Dorst's own draft of the film's female protagonist. - Drawing: © 1943-44 Bodil

Rønnow Dargis.

To the left is one of Preben Dorst's

own sketches of how he drew himself to the princess' figure and appearance. It

was this character that the management and the cartoonists accepted and

approved as a full expression of the film's quite young female protagonist, who

in her best moments could faintly resemble the famous Disney's Snow White

(1937), or perhaps rather of Princess Glory in Brd. Fleischer's feature

"Gulliver's Journey" (1939). - The sketch has belonged to Helge Hau,

who in 2001 donated it to Dansk Tegnefilms Historie. - The film image on the

right is a close up from the scene where the princess stands out on her balcony

and sings the touchingly beautiful text and melody "I feel like the bird

in the cage". - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S

Partly because of Dorst's concerns about having to animate the singing princess

in particular - he may have especially Disney's successful singing "Snow

White" in mind - the chief animators managed to convince Johnsen that it

would be a good idea, which could save many inconveniences at the same time.

and working hours, if one made some live action recordings in advance with the

girl who was to sing in the princess' voice. The idea was not to rotate, that

is, to draw, the live action recordings, but only to use these as a model for

the princess' movements and not least mouth positions during the song.

This photo shows the two

composers, Vilfred Kjær and Eric Christiansen, who during 1944-45

composed catchy music and some beautiful melodies for the feature film

"Fyrtøjet". The music was recorded by a 60-man orchestra under the

direction of Vilfred Kjær, and probably took place around the autumn of 1945,

and probably at Palladiums Studier in Hellerup. - Photo from the Film Program:

© 1946 Palladium A/S.

Therefore,

Johnsen accelerated the writing of an appropriate lyrics and music composed for

it. The text was written by Victor Skaarup and the melody composed by

the composer couple Vilfred Kjær and Eric Christiansen. It became

the beautiful song "I feel like the bird in the cage". To sing the

princess 'voice, after several rehearsals, the then member of the Radio Girls'

Choir, the only 14-year-old Kirsten Hermansen, had been summoned to

appear on a Saturday afternoon after the end of working hours at the studio in

Frederiksberggade 28. Here the photographer Marius Holdt was to film her in

half-total while she sang the said song. It was the leader of the Radio's

Girls' Choir, Lis Jakobsen, who together with Finn Rosenberg, Allan

Johnsen and Peter Toubro had chosen the beautifully singing Kirsten Hermansen

as a suitable voice for "Fyrtøjet"'s princess.

This photo, which is probably

from around the autumn of 1945, shows an example of how the recording of

dialogue and song took place in a sound studio, which here is probably at

Palladiums Studier in Hellerup. From left are (sitting on the bench) theater

and film director Svend Methling, the only 14-year-old Kirsten Hermansen, who

spoke and sang the princess' voice, and the actor Poul Reichhardt, who sang and

sang the soldier's voice. Kirsten Hermansen looked pretty much like this in the

picture when she sang "I feel like the bird in the cage" in 1944 at

the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28. The man in the background is a

sound engineer, but his name is not stated. - Photo from the Film Program: ©

1946 Palladium A/ S.

The

acoustic conditions in the drawing room were certainly not suitable for sound

recording, but it turned out that the song had already been recorded on steel

tape beforehand. It was therefore an arrangement whose sole purpose was to

produce a film recording, which the artist - in addition to the score - could

rely on when he had to time and animate the princess' movements and mouth

movements. A few meters in front of the film camera, a music desk had been set

up with the sheet music for Victor Skaarup's beautiful lyrics to Wilfred Kjærs

and Eric Christiansen's touching melody. The somewhat shy young singer took up

position behind the music stand and captivated everyone present with her

beautiful, singing interpretation of the princess' longing. Incidentally, it

was clear to everyone that the inspiration for the song and the melody was

taken from the "Snow White" film's song "Some Day My Prince Will

Come".

Here is the final version of

the princess in the feature film "Fyrtøjet", as Preben Dorst drew and

animated the character. In the best scenes with the princess, there is a hint

of 'life' in her, but often the animation of her seems completely out of step

with the film's soundtrack, which can be partly explained by the fact that song

and music were only recorded during 1945, where the vast majority of scenes

were long ago drawn and animated. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A /

S.

Unfortunately, it proved impossible for Preben Dorst to benefit from the filming of the singing Kirsten Hermansen, primarily because Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm did not have equipment for the purpose. And you could not even think that the artist would have to go back and forth between Frederiksberggade and e.g. Nordisk Films Teknik in Frihavnen, where he would have been able to study audio tapes and test films at the same time. Here the general lack of experience of management and animators came into the picture, because strangely no one at the time thought that the song could have been measured up and word for word and sentence by sentence had been marked on the photo list. It would undoubtedly have meant a better synchronization between sound and image than the case unfortunately became, while at the same time it would have been a great relief for the animator's work. Unfortunately, the result was not very successful, as the princess' movements in several scenes are not at all in harmony with the rhythm and content of her song, and the mouth movements were not drawn markedly enough to create the illusion of synchrony between image and sound. Dorst still had a lot to learn about animation and synchronism.

Some interjections

In light of what later happened in Danish cartoons, one can wonder today that none of the involved, relatively experienced animators at Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A / S at the time found it necessary with a definite teaching in animation and cartoon technique next to the actual production. At best, it was a kind of master teaching for the students who were then employed by the company. I, Harry Rasmussen, was actually the only employee at "Fyrtøjet" who can be considered a real student, namely primarily by Børge Hamberg. Neither Kaj Pindal nor Ib Steinaa had the status of students, but rather as intermediate artists, and according to their own statements, none of them learned to make cartoons in their time at "Fyrtøjet", where they otherwise worked under the guidance of such an experienced and knowledgeable artist and animator as Bjørn Frank Jensen. This situation may possibly be due to the fact that there was so little cartoon work to be had in Denmark at the time that practically none of the relatively few animators that existed in the country at the time dared to give e.g. the animation's 'secrets' and thus possibly weaken its own employment opportunities in the future.

It was also unseen in Denmark at the time with female animators, and female cartoonists were also a rarity, but gradually appeared at Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm. This was the case, for example, with Bodil Rønnow, who for some time was the only female intermediary among mere male ditto. During 1944, more and more female intermediaries were added, e.g. Karen Margrethe Nyborg and the probably Italian - or possibly Jewish - Miss. Zotsi, but more than a 4-5 pieces it was about as far as I do not remember. On the other hand, the number of male middlemen increased quite considerably, so that in 1945 there were probably around 100 middlemen and a similar number of leading ladies and "colorists".

The

increased number of employees of course required more space, and as it was not

possible to squeeze more people into the design studios in Frederiksberggade

and on Nørrebrogade, they rented a large room on the second floor of

Skræddernes Hus in Stengade in Nørrebro. The room was huge and was used as a

sewing room, where a large number of seamstresses sat all day bent over the

electric sewing machines and sewed uniforms for the Germans. To begin with, the

number of interpreters who were to work there on the spot did not revolve

around more than about a dozen pieces, and these had to clump together at the

far end of the sewing, behind a giant curtain, which was hung up between some

square pills. This was done partly to dim the daylight and partly to - if

possible - dampen the infernal noise from the many noisy sewing machines.

Mogens Mogensen was elected head of this department, who proved to be a

friendly, mature and knowledgeable department head. Unfortunately, it has not

been possible to find available photos from this department, which otherwise

could have been quite interesting, and which we will hear more about later.

In this photo from Dansk

Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S ’department at Nordisk Kollegium in Østerbro, the many

young ladies are seen concentrating on the drawing and coloring work on“

Fyrtøjet ”. Department manager Else Emmertsen is seen in the foreground on the

left. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to identify quite a few of the

talented and diligent girls, but in the front row it is probably Karen Hjerrild

and Jytte Claudi. - Photo source unknown. - In the inserted photo to the right,

Else Emmertsen is seen in 1941, at the time when she was department manager at

VEPRO. - Photo: Excerpt from Dansk Billed Central's group photo from VEPRO's

Christmas party 1941.

In the case of the inking ladies and the "colorists", those who had previously worked in the Nørrebrogade department were moved to some premises in Østerbro. Miss Bech alias Karen Bech alias Karen Egesholm can tell the following about this:

“At one point, we then moved up to premises at Nordisk Kollegium on Strandboulevarden. It was small with foreign students, so there was an entire floor on the 4th floor that the company rented. Here even more ladies came and we were divided into groups. Irmelin and I, who were now old rats, each got a group. We distributed the work and checked the result. It helped that we got some nice recommendations when we finished. We remember some of the names of the girls, but they were not there that long, so it's probably not that important [with the names of them]. ” (Karen Egeslund in a letter of October 20, 2001 to Harry Rasmussen).

The physical working conditions, equipment and work tools at Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S were generally extremely primitive, and would hardly have been approved by today's work supervision. Despite this, the enthusiasm of the staff was at the top, and the work discipline was generally good, just as sickness absence remained within acceptable limits. It was greatest among the ladies, probably for natural reasons, but absence was only rare for the key and in-between collaborators.

However, for most employees, these were quite young people who might have found it easier to accept the pay and working conditions than the older and more experienced ones. Moreover, unemployment was high at the time, and for young men who dreamed of becoming cartoonists, the number of possible jobs was limited. In short, it was important to take care of your work so that you could keep it as long as possible.

In the autumn and winter of

1943/44, the animation of "Fyrtøjet"'s many sequences and scenes progressed

quietly, but she was still filming a few meters of black and white line test

and finished color film. The first line tests were recorded on the old and

primitive trick table at Nordisk Films Teknik out in Frihavnen, where the

negative was also developed. The few meters of color film that had been

recorded up to this point had, as previously mentioned, been recorded partly on

Marius Holdt's trick table and partly on the primitive trick table at Nordisk

Films Teknik. Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S did not have any display equipment

itself, but initially rented it from the American rental company Warner Bros.,

which had offices and a display room in the large property that was and still

is on the corner of Rådhuspladsen and Jernbanegade. However, during 1942-43,

the situation forced Warner Bros. and other large American film rental

companies to close their Danish branches. Instead, Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm

entered into an agreement to show e.g. line tests at UFA in Nygade 3, which was

partly located relatively close to the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28,

and partly was the link to Agfa's film laboratories in Berlin.

To start: Danish Cartoon History

Next section: