To start: Danish Cartoon History

The cartoon "Fyrtøjet":

Problem Times

The first scenes that Marius Holdt recorded on his own newly installed trick table at the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28 were, as previously mentioned, the scenes with the astrologer at Rundetårn and the guard who round a street corner, which Bjørn Frank Jensen had drawn and animated already at the end of 1942 - the beginning of 1943. The situation was, however, that the only kind of color film that was possible to use at that time was Agfa Color, but at home Agfa did not have the special 35mm color developing and copying machines needed to get the negative film developed and copied. This could only happen at Agfa's laboratories in the UFA Stadt in Berlin. The contact for this was established via UFA’s Danish department, which was housed in the same building as Nygade Teatret, Nygade 3 in Copenhagen. Later, when conditions in the summer / autumn of 1944 deteriorated in Denmark as a result of an increasing number of strikes and popular uprisings and unrest, Allan Johnsen personally took on the risky task of transporting the exposed film negative to Berlin and after the development back to Copenhagen. He also brought home the working copy, which was tentatively edited by Henning Ørnbak, while the negative editing had to wait until further notice.

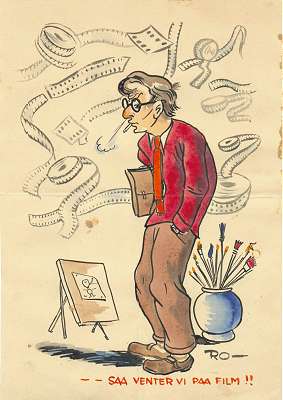

In this self-caricature from 1944-45, Finn Rosenberg has sought to give an impression of the great difficulties involved in obtaining negative and positive raw films for the production of "Fyrtøjet". In addition, the exposed film could only be developed and copied at Agfa in Berlin, because laboratory equipment for the production of color films was not yet available in Denmark. - The drawing was donated in 2003 to © Dansk Tegnefilms Historie by Mrs Gerda Johnsen.

During the same period, the situation had also worsened in Germany itself, with roughly nocturnal, Allied bombings of the big cities. Despite this, Allan Johnsen traveled tirelessly to Berlin - a couple of times accompanied by Finn Rosenberg, who according to his appearance was even of Jewish descent, but who had not been arrested during the Jewish action on October 2, 1943, and did not flee to Sweden or went underground on that occasion! He constantly continued his daily work as if there was peace and no danger. This was probably due to the fact that at that time it was not yet generally known in Denmark what terrible fate had befallen and still befallen Europe's Jewish population and other ethnic groups. But no sensible explanation can be given here as to how it could be done under the sometimes very tense conditions during the occupation that individual people of Jewish descent and clearly Jewish appearance, such as also Finn Rosenberg, untouched could continue their daily work and move around freely.

During one of Johnsen's stays in Berlin in the spring of 1944, when the Allied bombing of German cities had begun, e.g. one of UFA's laboratories was hit by a hit that completely destroyed the building. Allan Johnsen had Finn Rosenberg as a travel companion, and during the bombing they were in the laboratory building's shelter with some of the place's German employees. Neither of the two received as much as a scratch, but several Germans were killed on that occasion and several were seriously injured. The experience, however, meant a shock for Allan Johnsen and Finn Rosenberg, but especially for the latter, it was a traumatic experience that he probably never recovered from. Despite this, he continued his daily drawing work as long as it was required, and it was at least until after the liberation on May 5, 1945, yes, even longer, because Finn Rosenberg remained employed by Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A / S so far.

Later film, stage, radio and TV director Henning Ørnbak, who was employed by Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm in the spring of 1944, can tell about a similar episode when he was once Johnsen's companion on the trip to Berlin:

"In February 1945, Johnsen lured me to take him to Berlin, there in the middle of the war. We had to pick up the negative, which was Agfa color and therefore was developed in Berlin. With two backpacks we left and I remember Johnsen talked a lot with a German officer with a cap on the ferry to Germany.

The trip by train was interrupted by an alarm where everyone had to go out and lie in the ditch. In Berlin in the evening / night we waded through deep water-filled holes and houses with holes through previous windows so we could see the moon and it looked like a Dixner background [Dixner = Henning Dixner, who was the background painter on "Fyrtøjet"]. We stayed near Friederichstrasse and the next day Johnsen went to UFA after the negative. During the day there was an air raid and I was planted in a shelter and the sound of many bombings. That was the day the English wiped out Dresden (shown on 14 February). After the bombing, Johnsen showed up with the negative in two backpacks and we went, hanging on a truck, through a total chaos, with dead horses, power lines hanging down and the smell of gas and people flowing here and there in petticoats, etc.

For me, at first it was an incredible scenery. But when I saw Johnsen's blackened face, I understood the seriousness. Our hotel was also affected and we had to get out of town as soon as possible with only the two backpacks. Everything else was left behind.

On the way home, it turned out that Johnsen had "done the right thing" in entertaining himself with the officer on the trip. He made sure we got the negative without papers to take home. Puh-ha.” [Henning Ørnbak in a letter dated September 2, 2001].

Despite the difficult conditions due to the occupation, the work on "Fyrtøjet" continued quietly in the autumn and winter of 1943 until the spring of 1944. About the daily work and the atmosphere at the design studio in Frederiksberggade 28, Bodil Dargis, born Rønnow , Among other things. tell the following:

“I remember the drawing studio as something uniquely primitive, but nice. There was a good atmosphere between the characters, we did not know about drugs, ecstasy, burgers and diet pills. People cycled to work and wore the clothes they wore.

On festive occasions, it was "Pullimut", a kind of port wine, we enjoyed ourselves with. At those times, Allan Johnsen stayed away, I had the impression. He was a good boss, but at the same time I also experienced being called home to the department 2 summers, due to busyness. I was in the cottage without a phone connection, yet he found me. I think there was a bid from the grocery store.

The next summer I cycled around Funen and stayed at a youth hostel. The company also managed to call me home. I cycled to Middelfart and came with a freight steamer that sailed to Copenhagen at night.

At one point there was a state of emergency in Copenhagen, German soldiers had cordoned off Strøget. They stood with machine guns pointing up at us if we looked out the window.

I came cycling in the morning from Skovshoved, on the corner of Rådhuspladsen stood one of the signs, I think it was Børge Hamberg, he redirected me along Vestergade and showed me a shortcut by which I could get in and through to our own backyard in Frederiksberggade. Here, too, was an escape route for those who might need it.

The first year I was one girl among the cartoonists, I was offered to try animation, but said "no", unfortunately - I was the nice girl - without ambitions.

However, I became the sole intermediary for Preben Dorst, who drew the Princess, she should have the calm sliding movements. " (Bodil Rønnow Dargis in a letter dated 14.06.02 to Harry Rasmussen).

The state of emergency to which Bodil Rønnow alluded took place in both 1943 and 1944, and was in both cases imposed by the German occupation authorities as a result of sabotage, strikes and popular uprising. On August 29, 1943, the Danish co-operation government resigned in protest against the Germans' proposals and handed over the administration of the country to the department heads and directors-general. In 1944, this had serious consequences for the Danish population, namely, firstly, during the "People's Strike" and, secondly, in an increased number of clearing murders and Schalburg days against important Danish companies.

The concept of "Schalburgtage" was connected with the fact that as a direct result of the growing resistance and especially the sabotage against Danish companies, which were known for cooperating with the Germans, a military corps had been formed on 2 February 1943 under the name of the Schalburg Corps. Within the corps, a combat organization was formed at the same time with the aim of fighting "the enemy sabotage and terror in Denmark". From this arose the concept of Schalburgtage, and what it consisted of, the Danes would soon come to feel.

However, it was not only Danish saboteurs who the resistance fighters were derogatory and consistently described in the media, which caused problems for the Danish police, the Danish and German authorities, but also the English. On 27 January 1943, six English bombers unexpectedly stormed Copenhagen, dropping their bombs on Burmeister & Wain between the harbor and Strandgade. The reason for this was that the company cooperated with the Germans, and it was therefore important for the illegal Danish resistance movement that a strong warning signal was issued to the leaders of companies that produced and delivered goods to the Germans.

Unfortunately, the English pilots did not manage to avoid the bombs also hitting civilian properties, as the apartment blocks in Knippelsbrogade 2-6 were destroyed, just as the Sugar Factory at Langebrogade was hit and a violent fire broke out. Bombs also fell in the Island Brygge district, and since they were defectors and time bombs, several thousand people had to be evacuated and temporarily take up residence elsewhere. During the attack, 7 people were killed and many wounded, just as Christian Church was damaged. It was Copenhageners' first serious encounter with the war, which both the English and the Germans and other peoples had long ago felt the serious consequences of.

However, the occupation period was also more than just sabotage and schalburgtage, stabbing liquidations, clearing murders and the like, as serious consequences of the tense relationship between the German occupation authorities and the Danish population. It is a fact that entertainment life flourished despite various restrictions and prohibitions. This was especially true of the cinemas, which had crowned days, even though you could mainly only play Danish, French, Italian and German films. But the cinema audience, which at the time consisted of both younger, middle-aged and older people, was almost hungry to search into the darkness of the cinemas and to dream away from the not always equally pleasant lives and events for about an hour and a half. The radio newspaper and the newspapers, which in both cases were subject to German press censorship, brought news every day about the acts of war on both the Western and Eastern fronts, and about the pervasive crime, including the ever-increasing black market trade.

For my own part, of course, I followed what was going on with serious events all around, but that did not stop films and cinema repertoire from continuing to be of great interest to me. In July 1943, predominantly French films were played in cinemas, and only a few Swedish and even fewer Danish films, at least at this time. It is particularly interesting that a film like "Erotica" was played in the 11th week in the same cinema, namely Alexandra, which by the way became known for a fairly serious repertoire. However, I have not been able to identify the film, except that it is Hungarian, but the title alone has probably been enough to lure the 'Hussars' in. Since I was only 14 years old at the time and the movie was obviously banned for people under 16, I would not have been able to see it even if I had wanted to.

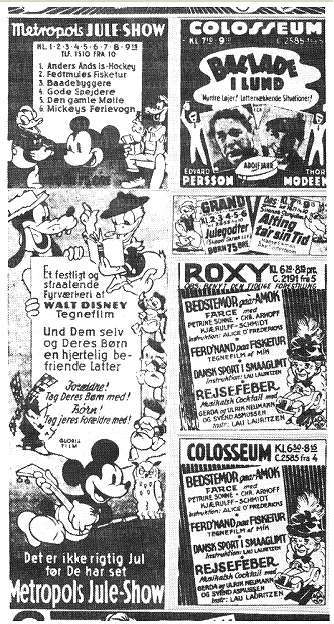

Typical Copenhagen cinema advertisements from 1943-44, but here from the autumn of 1944, where several cinemas play the short film program in which Mik's "Ferd'nand on a fishing trip" was included. In addition, a characteristic advertisement is seen for the annual "Metropol's Christmas Show", in this case with 6 slightly older Disney cartoons. The ads depicted are from Politiken, but could be from several Copenhagen newspapers.

One of the special joys for cartoon fans was that the annual "Metropol Christmas Show" could still be shown, probably because the German censor partly considered the cartoons harmless, and partly because they followed the psychological motto "if people are hungry or dissatisfied, then give them plays! ” The Danes may not have been literally hungry, but it was difficult for many - and especially for the families with workers and children - to get the daily bread on the table. The foods that were available were almost all subject to rationing, so that one had to have rationing labels in order to be able to buy the goods in question at all. The rationing labels, which people in carefully measured numbers received for free from the municipal offices, had therefore also become a commodity on the "black market", and often at such outrageous prices that only affluent people could afford to buy them.

The rations, of course, applied in particular to luxury goods, and especially those of foreign origin, such as coffee, tea, etc., as long or short as these were to be had at all. For people who e.g. were addicted to tobacco smoking in one form or another, times became increasingly difficult, partly because imports of American tobacco had ceased, and partly because the stocks of tobacco factories were gradually running out. To counteract this uncomfortable situation for smokers, they began to mix Danish tobacco into cigars, ceruts and shag, while the cigarettes still consisted exclusively of original tobacco. But on the other hand, there was a shortage of tobacco products in the shops, which for some took advantage of the situation to their own advantage, by partly selling the tobacco products, especially cigarettes, under the counter. It actually meant some form of black market trading and it was strictly forbidden. But I clearly remember how a tobacconist in Larsbjørnsstræde used this approach. The reason I was told was that Børge Hamberg, who, like several others in the design studio, was an avid cigarette smoker, one day asked me to go to the mentioned shop and try if I could buy one. pack cigarettes for him, because he had, so to speak, exhausted the 'quota' which the tobacconist allocated to his regular customers, and Børge belonged to them. In short, he was what in Copenhagen was called 'smøg embarrassed'. But I was not a smoker myself and had only tried to smoke once when my cousin Dennis and I were going to play adults. It tasted ad h. To, and I have pretty much never seriously smoked since, except for a few short periods later in my life. But when Børge gave me the money to buy the cigarettes for, he said: "You will have to buy a pipe too, because otherwise he will not sell you cigarettes!"

Incidentally, it should be added here that it was a rarity to see a woman smoke at that time, but there were a few exceptions, also in the drawing room, where a few of the girls had become addicted to cigarette smoking. This was especially true of the female head of the drawing and coloring department, but where she bought her cigarettes, I do not know, but she seemed to always have for her own consumption.

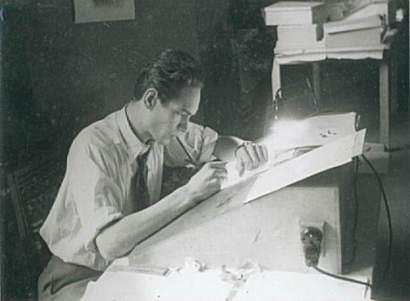

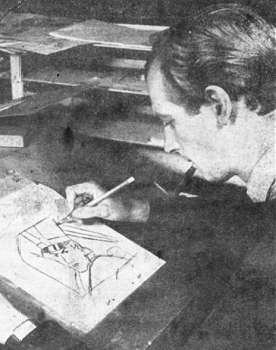

Børge Hamberg, like the other adult cartoonists and animators who worked on "Fyrtøjet", was a passionate cigarette smoker. It has probably calmed his nerves, because he was very excited for as a design studio and personnel manager at the design studio in Frederiksberggade 28, where he was the link between the management and the employees, a job that could often cause problems. Here, however, it is one of the many pipes he reluctantly acquired he has in his mouth. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

At that time I was only about 14 years old, and it was therefore probably not so likely that the tobacco dealer would sell tobacco products to a guy as young as me. The tobacconist, a tall, grumpy and fat guy with day-old stubble, and wearing a dark blue smock, stood behind the counter in the very small and narrow shop, looking inquisitively at me as I entered the shop. There were a few gentlemen in there when I arrived, but soon after it was my turn to be dispatched. "Do you smoke?" asked the man with the black-stained face inquisitorial. "Yeah-eh!" I mumbled as the blood rose to my head. "Reach!" he said and continued, "What are you going to have?" "Just a package North State!" I stammered. "But do you know that it is also necessary to buy a pipe?" he said almost ascertainingly, taking an ordinary but quite neat pipe out of a cupboard. Laying his pipe in front of him on the counter, he bent down at the same time and reached under the counter, from where he picked up a pack of cigarettes. Hot on the ears and a little nervous that he might regret selling the goods to me, I hurried to pay and hurried out of the store. I know that Børge Hamberg had gradually amassed a nice stock of pipes, which he either sold or gave away because he did not smoke a pipe himself. However, there were also several other of the designers in the drawing room who eventually got a collection of unnecessary pipes. But that was one of the conditions for at least some smokers back then.

Well back at the drawing room again, Børge Hamberg was of course more than happy that I had managed to get him a pack of cigarettes, and the same afternoon he came and gave me a piece of whipped cream, which he knew I liked very much. Cream duck tasted heavenly, many thought in the drawing room, and it was therefore a regular event, especially in the summer, that someone, and it was sometimes me, was sent or even chose to go to La Glace in Skoubogade, for to buy a certain number of pieces of whipped cream, which you then soiled yourself with afterwards.

Incidentally, several of the studio's male smokers had switched to pipe smoking because it was easier to get pipe tobacco than cigarettes, and it was Preben Dorst who started a craze with the so-called meerschaum pipes. This type of pipe was relatively expensive to buy, so there was a certain prestige in owning one or more. It was so lucky at that time that there was a distinguished and well-stocked pipe shop on the corner of Kattesundet and Vestergade, and it was here that the male cartoonists bought their pipes and pipe tobacco.

But otherwise, there were a number of small and slightly larger tobacconists, who were either reported or caught red-handed by plainclothes police, not only to sell tobacco products "under the counter", but who also conditioned that customers bought e.g. a pipe or other goods on the same occasion. Such illegalities were taken very seriously, and the persons concerned were not infrequently arrested and, as a rule, fined and, in particularly serious cases, confiscated for illegal gain.

A real Copenhagen event took place on August 15, 1943, as Tivoli could celebrate its 100th birthday on this day, and on that occasion the garden was allowed to stay open until 24. Copenhageners then also flocked to take advantage of another opportunity to have fun and for a while forget about everyday problems and inconveniences.

However, the acts of sabotage against the Armed Forces and the so-called Armed Forces continued and intensified, that is, the people, factories and companies that supplied goods to the Germans. In addition, sabotage against the Danish railways had become increasingly widespread and extensive. This prompted the government and the co-operation committee to issue a 'call' on August 21, which was sanctioned by the king and in which it urged the people in general and the resistance movement in particular "not to indulge or allow themselves to be deceived into unintentional actions…"

However, the call had the exact opposite effect of what one might have thought, for it led to 400 shop stewards from the capital's trade unions and political organizations on August 24 adopting a resolution for the capital's workers. The resolution ignored the Government's and the Cooperation Committee's call to maintain calm and order, which, among other things, was underlined by the fact that the Forum was destroyed the same day by a sabotage operation. And on August 26, street riots and the crowd on City Hall Square led police to arrest about 120 people. I myself experienced up close the riots on the Town Hall Square, where German soldiers on motorcycles with manned sidecars drove around on the sidewalks and drove the pedestrians away. On the Town Hall Square itself, where many people stayed, German tanks patrolled back and forth, just to emphasize the seriousness of the situation, and there were also a few serious shooting episodes. The government's call of August 21 was repeated and printed in all the newspapers on August 28, and the magazine's editorial writers called for calm and sober behavior in the light of the serious situation that had arisen and did not openly express its displeasure. the German authorities and their Danish henchmen.

The tense situation led the German High Command to demand that the Danish government introduce a state of emergency throughout the country, with a ban on strikes, the introduction of a curfew (curfew), German press censorship, standard courts and the death penalty for sabotage. These demands were refused by the Danish government, which at the time was led by the pro-German Erik Scavenius, after which the German commander in Denmark, General Heinrich von Hanneken, on August 29 proclaimed a state of military emergency in Denmark. The army and navy crew were immediately interned, but most of the navy's ships in the port of Copenhagen were sunk by officers and crew, and it was a strange sight to see the sunken warships rising halfway up the water. However, some of the fleet's vessels managed to escape to Sweden. But the situation had also required casualties, as 12 Danish soldiers from the army and navy had fallen for German bullets on August 29.

As a direct consequence of the German military state of emergency, the coalition government immediately chose to resign and leave the control of the country to the ministries, as the rest of the occupation, ie. until May 5, 1945, was headed by the Heads of Department and the Directors-General.

One of the things that meant a great deal of inconvenience for Copenhageners was the Germans' introduction of a so-called curfew, which in practice meant that it was forbidden to travel outside without a special pass during the time at 21 to kl. 5. Because it had the immediate consequence that e.g. restaurants had to close and cinemas and theaters had to end the performances so early that the audience could reach home before 1 p.m. 21. In the case of the theaters, this led to them introducing afternoon performances, and as something very special, this year's Hornbæk revue was performed in the Saga cinema at 7am, even for full house, which would not say so little, for the cinema had 2000 seats!

On September 9, 1943, the German authorities fined Copenhagen a fine of DKK 1 million. Kroner, which should have been paid before September 10 at 17. The reason was that a German caretaker had been shot by a cyclist. On September 21, it was wrong again, as Greater Copenhagen was fined DKK 500,000 because another cyclist had shot and wounded a German soldier. The largest fine was, however, Copenhagen was sentenced on October 28 as a result of sabotage against Café Mokka in Frederiksberggade, during which four Germans and a Dane were killed and 14 Germans and 26 Danes were injured.

This is especially the last episode that Bodil Rønnow alludes to in her previously quoted letter, where she mentions that Strøget was cordoned off by German soldiers, who stood down on the street and pointed at us with their submachine guns if we dared to look out. to the windows. It must have been the day after the attack in the morning that this incident took place, during which German soldiers and emergency vehicles had cordoned off Frederiksberggade at both ends and at the side streets Mikkel Bryggersgade and Kattesundet. In those places, German-armed German guards were posted, partly to prevent people from getting out and partly into the street. While some German soldiers and German police were busy investigating the partially destroyed Café Mokka, others were investigating the various houses and stairwells, presumably in an attempt to possibly find traces of the saboteurs.

At one point, while the action was taking place down the street, I and a couple of others in the drawing room dared to look out of one of the windows, and we saw that several people had sought refuge and were standing together at the slightly secluded double entrance to the jeweler's shop. and baker Reinhardt van Hauen. A middle-aged, well-dressed lady with a hat, bent carelessly forward, to look across the street in the direction of Gl. Torv / Nytorv. Suddenly it sounded like a "pouf", and at the same moment the lady in question fell forward and down the sidewalk, where she lay motionless. Immediately after, a thick pool of blood spread outside the lady's head, and the people standing with her shouted and called for an ambulance. One of the two German guards, who was stationed at the barbed wire barrier next to Mikkel Bryggersgade, approached the shouting and made threatening signs that they should remain calm. Then he turned on his heel and went back to his post, seemingly completely unaffected by the wounded and perhaps dying lady lying on the sidewalk.

Time falls long in such dramatic situations, but in my memory it seems as if it took at least about twenty minutes to half an hour before a Danish ambulance arrived at Mikkel Bryggersgade, where it did stop behind the barbed wire barrier. The two Danish rescuers got ready with the stretcher and wanted to pass the barrier, to go and pick up the wounded lady, but the German guards sent them back behind the barrier, where they had to wait until further notice.

The indignation spread among us cartoonists, for it was clear that the German guards did not intend to help the poor woman, who was still lying motionless on the sidewalk, where the pool of blood in front of her head had meanwhile grown larger. But we could actually do nothing, because the Germans were clearly only willing to take revenge, by letting the woman bleed to death. Only when the action was called off about an hour later were the two ambulance people allowed to pick up the lifeless woman, and since they drove away with her without a siren, it must be assumed that they had found her dead.

Meanwhile, two heavily armed German policemen had also been up in No. 28 and inside our drawing studio, where they were completely silent, scowling and with heavy boot trampling, and especially with the submachine guns in threatening position, the premises went through, probably in the hope of being able to find someone or something that seemed suspicious and that could possibly be linked to the sabotage operation carried out shortly before. The two Germans were eerie to look at in their thick gray-green uniforms and the distinctive German steel helmets that went all the way down over their heads and hid their foreheads, ears and necks, so that the men appeared more like a kind of robot than like humans. In addition, there was the large semi-oval iron plate, which they each had hanging in a chain around the neck and down the front of the chest. In this case, however, they went again, and without remarks of any kind. This behavior in itself seemed eerie and threatening, leaving a depressed mood in the drawing studio.

Incidentally, we never heard anything later about whether the unfortunate woman who was hit by one of the German guards' sharp shots had survived or whether she was dead, but we guessed at the last.

The military state of emergency was not lifted until October 6, 1943, with the exception of the bans on strikes and assemblies, while the curfew continued to be maintained, but was eased to 6 p.m. 23-4 during the Christmas days 24 - 27 December. During the years of occupation, the New Year was celebrated without the firing of fireworks, as this had been banned as early as 1940 and lasted until 1944. And due to the curfew, the New Year parties in private homes stretched to the whole night, which I clearly remember, for one was completely groggy on New Year's morning, even if one had not drunk either beer or spirits. It was unusual to be up for so long. The curfew was not lifted until February 10, 1944.

The action against the Danish Jews

On the night of October 2, 1943, one of the most shameful German actions against the Danish population took place, namely what has been called the "action against the Danish Jews". As is well known, Hitler blamed the Jews for all of Germany's misfortunes from the very beginning, and since he had promised his faithful German people that he would provide "the final solution to the Jewish question," the Jews in Germany and later in the occupied lands were exposed a persecution, arrest, ill-treatment and execution that is unparalleled in world history.

On the night of October 2, 1943, the trip had come to the Danish Jews, who in part were brutally awakened in the middle of the night and declared arrested. They were only allowed to take the most needy things with them before being driven to temporary collection points, from where they were soon transported to the German concentration camp Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia. The transport took place in cattle wagons, where the prisoners were usually crammed so close together that they had to take turns sitting down. To their relief, there was only a single bucket in one corner, and the prisoners received neither food nor water during the often day-long transports to the concentration camp, which for most would mean either gassing or further starvation and forced labor until death.

However, there were brave Danes, including Allan Johnsen - who only very few knew anything about at the time - ready to help as many of the Danish Jews as possible to avoid the German arrests without thinking about the risk to themselves. Initially, the Jews in question were kept hidden in non-Jewish homes until an escape route had been arranged across the Sound to the free Sweden. Fortunately, the vast majority of Danish Jews managed to escape to the Swedish brother land, as if not with a kiss, but nevertheless received the refugees and arranged for their stay during the occupation of Denmark. But unfortunately there were also a number of Jews who failed to avoid German persecution and arrest, not least because there were Danes who saw nothing wrong or criminal in identifying their Danish citizens, or who might have reluctance or resentment or outright hatred against these. Unfortunately, this is how some people are.

Later it could be concluded that the action against the Danish Jews had basically been a failure, as out of 7000 Jews only the Germans managed to arrest 202. The many who escaped went underground and a large part of these remained in the time after helped to flee to Sweden. But some - perhaps the most courageous or foolhardy? - stayed in Denmark, and made it through in the approximately 7 months that were to pass, until Denmark's liberation.

As mentioned earlier, October 2 was also my confirmation day, but at that time I did not yet know anything about the action that the German authorities, at the direct command of Hitler, had launched at night. In addition, ordinary Danes, who had plenty of problems and difficulties in everyday life, closed their eyes to the injustices and atrocities that took place just outside their own front door, and closed themselves inside an almost hermetically sealed private sphere.

"The Show must go on"

But despite all the external restrictions and difficulties, including especially the curfew, the work on "Fyrtøjet" went on quietly, because it was important to get the film finished within a reasonable time. Moreover, the work, perhaps especially for the animators, was not only a matter of making the necessary money, but rather the prestige of and a deep satisfaction by trying to bring to life the drawn and animated characters, who were each responsible for. The animators were therefore first and foremost artists and secondarily employees, and this applied to all - or rather the relatively few - who were key artists on "Fyrtøjet". The few consisted of Børge Hamberg, Bjørn Frank Jensen, Preben Dorst, Otto Jacobsen, Kjeld Simonsen and - from June 1944 - Harry Rasmussen. To this can be added the two animators who only worked for a very short time on "Fyrtøjet": Erik Christensen and Erik Rus.

In the autumn of 1943, the original small staff of animators had been augmented with a truly experienced, professional and highly efficient animator, namely the long-mentioned Kjeld Simonsen, colloquially called Simon. To begin with, he sat occasionally and worked at the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28, where he got a place directly opposite Bjørn Frank Jensen, so the two sat facing each other. However, this did not mean that they used the situation to have neither short nor long conversations, because both were by nature silent and quiet people, who were humble towards their respective work and did not make up for their position as highly regarded and respected cartoonists and animators . They both concentrated heavily on the work itself.

In addition to his work on "Fyrtøjet", Simon also had a number of freelance assignments of various kinds that had to be taken care of. As soon as he therefore felt familiar with the animation tasks on "Fyrtøjet", he had been entrusted with, he sat at home on a daily basis at his own studio in Holte and worked. It is perhaps therefore not so strange that his animation style to some extent came to differ from that of the other animators. Simon drew his characters with rounded lines, which was an advantage in connection with decidedly comic characters, but when he e.g. drawing the soldier and the princess, what he came to in the film's ending sequences, it was a disadvantage because these characters thereby lost their original character. Simon's animation, which used all the basic tools of the subject, such as anticipation, overlapping action, squash and stretch, take etc., was also excessively soft and often a little too slow in the movements, so in some cases it almost looked as if the figures were balloons floating lightly and elegantly across the ground, too even though they really should have had weight. Still, overall, Simon's animation must be considered excellent at the time.

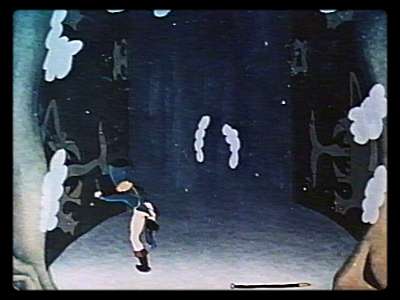

Some of the earliest scenes that Simon drew and animated were the moon where the sleepwalker stands up and the cat that jumps down from the ridge. The animation of the moon works well enough, but the cat moves far too slowly and just 'floats' down from the roof. In principle, the same was the case with some rats seeking shelter in their cave behind a cornerstone of the house in which they live. Simon's drawing and animation style was in itself, so it involuntarily contributed to the slight stylistic confusion and inequality that unfortunately characterizes the feature cartoon "Fyrtøjet".

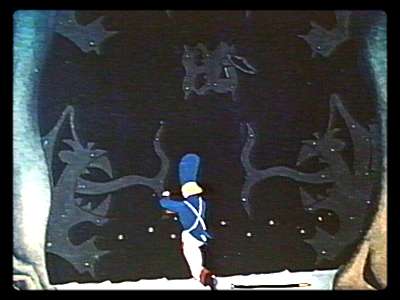

This film image shows the sleepy moon that has just risen over the rooftops. It was one of the first scenes that Simon animated for "Fyrtøjet", and completely in the characteristic drawing and animation style for him, for which he had taken inspiration, partly from Disney and partly from his Danish teachers, Myller and Mik. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A / S.

Here is one of the first scenes that Simon drew and animated for "Fyrtøjet". He designed the figures himself, which thereby came to differ somewhat from the style in which the figures in the film had so far been drawn. The background is painted by Finn Rosenberg: - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Another of the earliest of Simon's scenes for "Fyrtøjet". A pair of rats seek shelter in their cave, which has an entrance behind a high rock at a house corner. Also in this case, Simon's design and animation style differed markedly from the other animators' way of drawing and animating. But Simon's characters were still both well-drawn and comical in their own way. The background painted by Finn Rosenberg. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A / S.

Some cartoonists - and this may be especially true of animators - never really grow up, but 'play' their way through life, which they would rather see more like the cartoon world's fantasy world, than the often harsh reality, which at times seems devoid of bright spots. At the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade, it happened regularly that some of the cartoonists were gripped by madness and made fun of the basically serious work it is to make cartoons.

Here, Preben Dorst is seen in the role of the witch in "Fyrtøjet". He was only dressed up for fun, as it was one of those inventions that could occasionally suddenly catch some of the characters, especially when and if photographer "Jømme" were nearby and could immortalize the situation. After all, there is a bit of an actor in any animator, and should be too. - Photo: © 1943 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Here is another situation in which Preben Dorst was also involved, here, however, dressed as the king with a fur collar around his neck. The overturned chair and the cardboard tube must mimic a cannon that the little soldier - in the form of me, Harry Rasmussen (far left) - is preparing to fire. In the background, some of the characters are pointing, namely towards the cross that the court lady has drawn on the inn's gate. The man on the far right, who kneels down behind Dorst, I unfortunately do not remember the name of. - Photo: © 1943 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Christmas fun - after all

We were now in December 1943 and Christmas and the New Year were approaching, and characteristic of the Danes was that despite rationing and saving times, the vast majority would prefer to celebrate Christmas as in the "good old days". Human memory is usually not long-term, which is probably mainly due to the fact that each generation largely only remembers what has happened within their own lifetime, yes, often not even that. Forgotten for most was World War I and the world economic crisis and the consequent high unemployment in the 1930s. And the Danes would also rather forget the present with its hitherto threatening prospects due to the war and the occupation. Christmas, with its centuries-old traditions, was therefore a welcome opportunity to forget the world around it for a while and hide in the coziness of the immediate family.

The cartoonists and perhaps especially the cartoon girls in the drawing studio were no exception from the rest of the Danish population with regard to Christmas. Therefore, one of the last working days, in this case a Friday, was gathered for a Christmas lunch after the end of working hours. In particular, they drank quite nicely from what was available at that time of beer and wine, and of the latter kind one could only get Danish wine, including port wine, which was quickly dubbed "Pullimut". If you got enough of it, you simply got drunk. This in connection with the fact that due to the curfew had to endure until the next morning, contributed to the fact that some of the characters in a mixture of madness and drunkenness behaved like crazy and made the drawing room look like a battlefield.

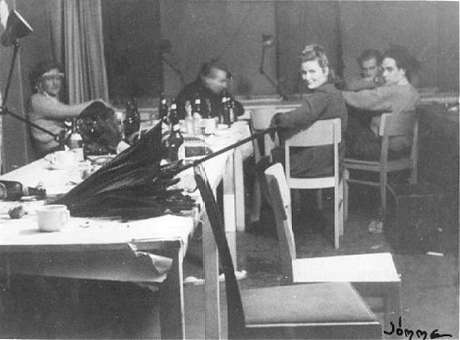

Christmas coziness - or perhaps rather Christmas coziness - at the design studio in Frederiksberggade 28. After a long evening and night, the otherwise nice and tidy room came to look like in the picture here. However, care was taken to ensure that everything was put in order before the start of working hours the next morning, for a sight like this hated neither Allan Johnsen nor Peter Toubro, who never himself took part in such excesses. - Photo: © 1943 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

In this photo, the same situation is seen as above, but here the people in the picture are recognizable. It is from left Torben Strandgaard, Helge Hau, Bodil Rønnow, Børge Hamberg and at the very back Mogens Mogensen. I myself was also present on such occasions, but stayed with several other illustrators somewhere else in the large room where the photographer did not point his camera. - Photo: © 1943 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

It was also on such occasions that competition could arise in particular between some of the men for the favor of the few women present. It was especially Otto Jacobsen, who at the time was single, who lost his temper when he got something to drink, and if he did not feel lucky, he could go crazy and destroy chairs and other furniture. The next day, when he had become sober, he could not fathom that it was he who had made as much havoc as was the case, and full of self-blame he naturally offered to replace the broken things.

It went differently quietly and cozy when some of the studio's employees held a Christmas party on Christmas Eve itself, where one or more of the girls had brought home-baked cookies and replacement coffee or tea was served. In addition, the ‘house orchestra’ or individual members of this played Christmas tunes, but in a modern, slightly jazzified version. Nostalgia was in the spotlight for a short while before finishing and the cartoonists and cartoonists put on their winter clothes and trudged out into the December darkness, heading in different directions towards the homes in the different parts of the city, either by bicycle with dazzling bicycle light or by dimly lit tram, for it was the most common means of transport at that time. The city lay in semi-darkness, which was primarily due to the introduced lighting restrictions and injunctions for blackout curtains both in private homes and in offices and shops. By the way, there were not many private cars, and not at all when the rationing of petrol really took off. And the few taxis that existed at the time could not always get petrol either, but at one point ran exclusively on so-called gas generator, a monster that also became common driving force for trucks. But the fuel used for these generators was also rationed, so therefore one could occasionally see the peculiar view that e.g. taxis were pulled by horses!

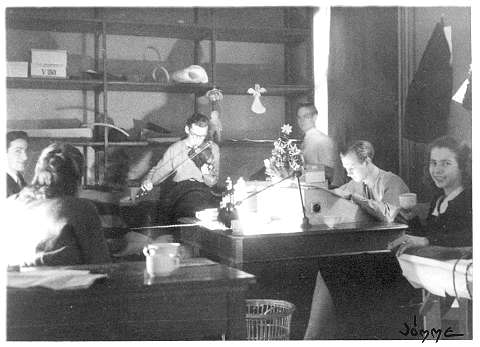

Here, a small part of the studio's staff is seen during a cozy get-together on Christmas Eve itself, shortly before the end of working hours. From the far left you can see Bjørn Frank Jensen's profile, then (with her back to) Bodil Rønnow, Finn Rosenberg with his dear violin, and partly behind the small, decorated Christmas tree, Børge Hamberg, in-between artist Erik Mogensen (at the drawing desk) and Jenny Holmqvist. Notice the shelves in the background. It was here that "Bjørn" or "Largo" had the cardboard boxes standing in which the various scenes were stored. Such a box is seen at the top left. - Photo: © 1943 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Here, the situation is largely the same as above, but where Bodil Rønnow is not in the picture. To the left Karen Margrethe Nyborg, who is looking towards the photographer. Finn Rosenberg still plays the violin, while Børge Hamberg probably plays his banjo. Erik Mogensen is still sitting and drawing, and Jenny Holmqvist is still looking at the photographer. Preben Dorst does the same on the far right. - Photo: © 1943 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

The work goes on… after all

After the New Year, which was celebrated without fireworks due to a ban, the daily work began again, also at Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A / S 'drawing studios around the city. But since it was limited what I myself knew and know about the departments that were out in Nørrebro and Østerbro, and to my knowledge there are not very many photos from there, it must still be the main department in Frederiksberggade 28, which is the central in this report.

This photo must probably come from the drawing and coloring department in either Nørrebro or Østerbro, and it is at least in-betweener artist Helge Hau, who is seen a little in the background to the right, where he flips through a stack of drawings. His presence here was probably related to the fact that he handed over one of the scenes he had in-between drawn for inking and coloring. The pretty young lady in the foreground is unfortunately unknown to me. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

In this photo from the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28, Karen Margrethe Nyborg is seen, who was one of the few female in-between artists who worked on "Fyrtøjet". Such pretty girls occasionally gave rise to amorous conflicts between individual male employees, in this case between Otto Jacobsen and Bjørn Frank Jensen, who both courted in her favor. The girl clearly preferred Bjørn Frank Jensen, which made Otto Jacobsen get jealous for a few days. Then it was forgotten and life went on. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Another situation picture from the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28. Here are the in-between cartoonists Erling Bentsen and Bente Nielsson, who by the way later married each other. Bente Nielsson occasionally also assisted Marius Holdt during recordings on the trick table. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

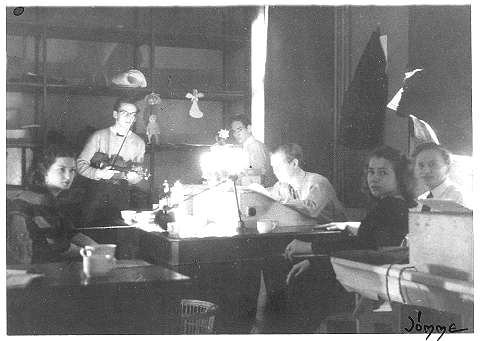

In this press photo, Bente Nielsson is seen on the left, assisting the photographer, Marius Holdt (in the middle and with his back to), while Bodil Rønnow (on the right) watches during the recording on the trick table of a scene for "Fyrtøjet". - Photo: © 1944 Ulf Nielsen / Politiken.

After the New Year, Børge Hamberg went on to draw and animate the smallest of the witch's three dogs, as it is actually this one that plays the biggest role in the film. He started with a close up of the dog's face, where the eyes rotate and that tones the image of a teacup into each eye. Incidentally, this animation was also used in the presentation of the other two dogs, but such that the teacups had been replaced with mill wheels and Round Tower, respectively. As usual, I was his in-between artist also on this animation, which was very simple, because it was only about in-between drawing the rotating pupils.

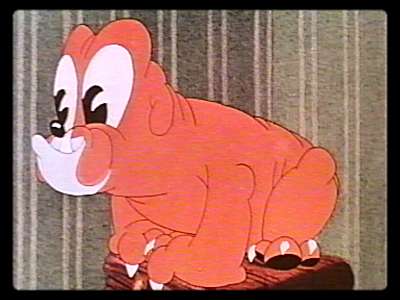

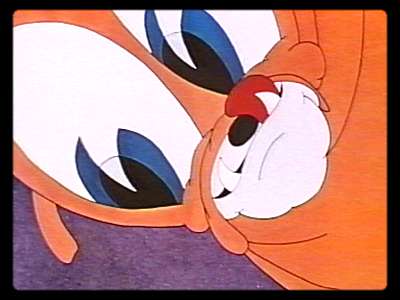

Above is the first scene with the witch's dogs, namely the smallest of these, the one with eyes as big as teacups, which Børge Hamberg began to draw and animate just after New Year 1943/44. For reasons of economy, the same animation was also used in the presentation of the other two dogs, simply by replacing the teacups with resp. mill wheels and Round Tower. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

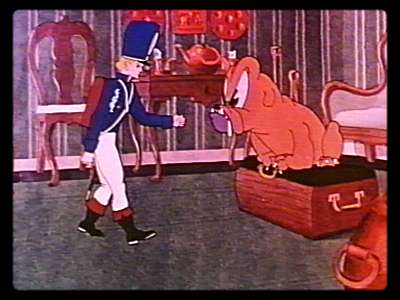

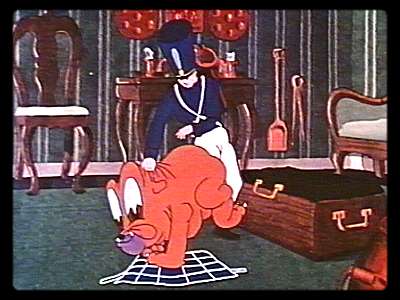

The next scene with the smallest of the dogs, Børge Hamberg chose to draw and animate, was the one where the soldier arrives at the room where the dog is sitting on top of the money box it is to guard. Using the witch's apron, the soldier entices the dog to jump down from the coffin lid, which he can then freely open and supply himself with as much copper money as he wants and can carry with him.

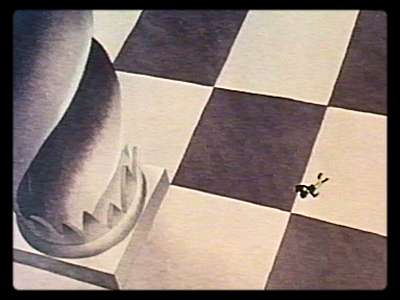

One of the first scenes, Børge Hamberg drew and animated with the smallest of the witch's three dogs, the one guarding the treasure chest with copper money. The soldier, who was of course key-drawn by Hamberg, was intermediate-drawn by Arne "Jømme" Jørgensen, while the dog was intermediate-drawn by Harry Rasmussen. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

One of the reasons why Børge Hamberg chose to continue his animation work by drawing and animating the smallest of the three dogs was that the soldier only plays a minor role in some of these scenes. Hamberg continued to hesitate to draw the soldier until he felt confident enough to seriously move forward with this demanding figure. The second reason was that he and the management now wanted to see how this dog and its character in particular came to stand out in the context. Therefore, Hamberg went with great energy and optimism to draw and animate some of the scenes with this dog, in which the soldier appears only to a lesser extent. In this way he could at the same time practice drawing and animating the main character of the film.

It turned out to the great joy of the management that Hamberg's Animation of the little dog was top notch, as he actually appeared alive and behaved like a dog. When the soldier has just arrived, the dog is at first repulsive and growls at him, but after taking out the witch's scarf, it changes position and waggles its tail.

Here is the little dog, who is so happy at the sight of the witch's apron that it starts wagging its tail and licking its mouth. With this animation, Børge Hamberg showed his great ability and strength as a character animator. The dog is also here in-between drawn by Harry Rasmussen, who in this way was partly trained in the difficult art of animation and partly prepared to later take over the animation of the little dog. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

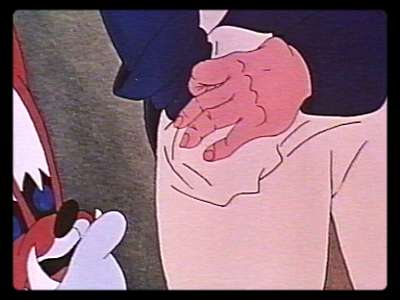

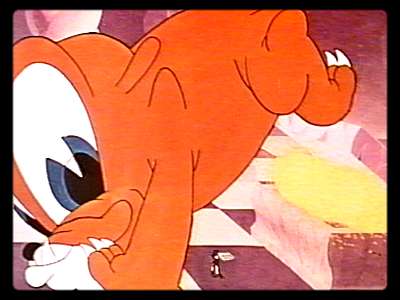

The witch's blue checkered apron is the lure that makes the dog be benevolent and lets the soldier help himself down from the money box so he can open the lid and supply himself with copper coins. However, he is not very satisfied with the ordinary copper pennies and has not yet understood that the dogs in the next two chambers guard silver and gold money, respectively, which have a significantly greater value than the copper money.

Here the soldier hauls the little dog down from the coffin lid, to put it on the witch's blue-checkered apron, whose smell it apparently recognizes and is therefore benevolent towards the soldier. In this scene, both the soldier and the dog are drawn by Harry Rasmussen, who, however, only rarely drew the soldier. In addition, in Børge Hamberg's opinion, the figure was too serious and difficult for a 14-year-old. Later, however, he changed his mind. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

At that time, Børge Hamberg also key-drawn a close up of the money box, where you see the soldier's hand grab down and almost shovel up the copper coins. This scene was also in-between drawn by Harry Rasmussen. The same was true of the following scene, in which one sees a close up of the soldier filling his trouser pocket with the coins, all the while the dog looks interested. - Photos from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S

The next scene with the dog, Børge Hamberg drew and animated, was the one where the soldier entices the little dog to jump up on the coffin lid again and sit down again, as he naturally intends to move on to the next chamber.

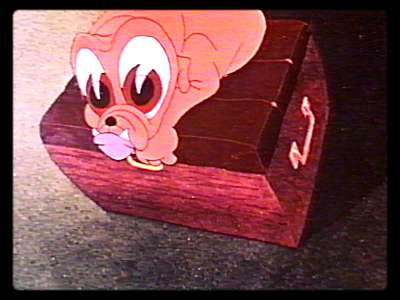

Here the little dog has jumped up on the money box again, where it lies down, not taking care of the soldier leaving its chamber, to go to the next room, where it is the dog with eyes as big as mill wheels, who guards the coffin with silver money. Again, the dog is in-between drawn by Harry Rasmussen. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

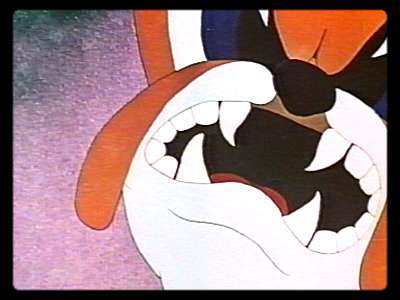

However, Børge Hamberg gradually got so good at drawing and animating the smallest of the three dogs that he wanted to continue drawing a few more scenes with this one before he had to resume the animation of the most difficult scenes with the soldier. It became the scene where the soldier for the first time estimated the magic fire because he wanted to light a wax candle in his lousy attic room at the inn. After all, he has been banished to the attic because he has thoughtlessly squandered all his money. To his great astonishment, the smallest of the three dogs arrives flux at the second, and of course without it happening through the door. To his even greater surprise, it also turns out that the dog can also speak, initially saying: "What does my master command !?"

The little dog, as to the great surprise of the soldier it turns out to be able to speak and says: "What does my lord command !?" Although Børge Hamberg had no soundtrack to animate, in this and the following scenes he managed to achieve a synchronicity between sound and image, which unfortunately belonged to the rarity of "Fyrtøjet". - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S .

With the animation for this and the following scenes, I was able to really study how Hamberg coped with character animation and drawing mouth movements. During the in-between drawing, I sensed that this was an animation of a quality and a standard that was top class. It was therefore a great pleasure and satisfaction to be allowed to draw scenes like this one, where you got close to the essence of the animation, which is the play.

Here the dog tells the soldier how to use the lighter alias Fyrtøjet when he wants to call for the help of the three dogs. If he hits the lighter once, the little dog comes himself, twice, then comes his big brother, and three times, then the dog comes with eyes as big as the Round Tower. "Then get me some money!" says the soldier, and flux the dog is gone, for immediately after returning with a bag of money. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

The little dog immediately returns to the soldier's room with a whole bag of money, which he has picked up in his treasure chest out in the witch's hollow tree. It is well enough breathless after the trip, but is visibly happy to be able to do the soldier a favor. This scene is also in-between drawn by Harry Rasmussen. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

During the first months of 1944, Børge Hamberg also drew and animated some scenes with the soldier, as he is confronted with the largest of the three dogs, the one guarding the treasure chest with the gold coins. But still, the sequences and scenes of the film were not made in action order, and therefore these were not yet available in continuous order. E.g. the soldier's difficulty in opening the giant door into the above - mentioned dog's chamber was not made until the autumn of 1944, while the immediately following scenes in the sequence were made first, namely, around February-March 1944.

Here is a close up of the soldier, as he at the sight of the giant dog, terrified, holds his one arm shielding up in front of his face. The soldier is drawn and animated by Børge Hamberg and the in-betweens by Mogens Mogensen. The background is painted by Finn Rosenberg. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

A subsequent scene in the same sequence as above: As the soldier enters the large dog's chamber, the dog's eyes emit like two searchlights following the soldier, hesitantly approaching the giant dog's seat on top of the treasure chest with the gold coins. Animation: Børge Hamberg. In-between drawing: Harry Rasmussen. Background: Finn Rosenberg. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A / S.

This is followed by a series of images from "Fyrtøjet", each of which represents a scene in the running sequence. The soldier is drawn and animated by Børge Hamberg and in-between drawn by Mogens Mogensen, the dog is also drawn and animated by Børge Hamberg, but in-between drawn by Harry Rasmussen. The backgrounds are painted by Finn Rosenberg:

The images in the sequence shown above are, with permission from Palladium A/S, reproduced directly from the excellent VHS version of "Fyrtøjet", which was sent to the market several years ago. - © 1946 Palladium A / S.

The sequence is longer and includes more scenes than those shown above, but these can serve to show a course of action with the soldier and one of the three dogs. The animation of the soldier in the scenes in the sequence in which he appears shows with all the desired clarity that Børge Hamberg had now gained control of the soldier's movements and character. And the movements were solely drawn and animated based on the animator's ability for motion analysis, timing and key drawing. There was thus no question of using rotoscopy, ie. of live action footage as a basis for the animation.

In between his interdisciplinary work for Børge Hamberg, Mogens Mogensen also had the opportunity to draw and animate some scenes with the soldier, which he proved good at. However, his drawing style differed to some extent from Børge Hamberg's drawing and animation style, as the scenes for which Mogens Mogensen was responsible seem more naturalistic with a tendency towards a certain ‘stiffness’. A clear sign that Mogensen was still untrained as a cartoonist and especially as an animator.

The images in the sequence shown above are, with permission from Palladium A/S, reproduced directly from the excellent VHS version of "Fyrtøjet", which was sent to the market several years ago. - © 1946 Palladium A/S.

The sequence is longer and includes more scenes than those shown above, but these can serve to show a course of action with the soldier and one of the three dogs. The animation of the soldier in the scenes in the sequence in which he appears shows with all the desired clarity that Børge Hamberg had now gained control of the soldier's movements and character. And the movements were solely drawn and animated based on the animator's ability for motion analysis, timing and key drawing. There was thus no question of using rotoscopy, ie. of live action footage as a basis for the animation.

In between his interdisciplinary work for Børge Hamberg, Mogens Mogensen also had the opportunity to draw and animate some scenes with the soldier, which he proved good at. However, his drawing style differed to some extent from Børge Hamberg's drawing and animation style, as the scenes for which Mogens Mogensen was responsible seem more naturalistic with a tendency towards a certain ‘stiffness’. A clear sign that Mogensen was still untrained as a cartoonist and especially as an animator.

Here, Mogens Mogensen is seen in the middle drawing the scene in "Fyrtøjet", in which the soldier has raised his saber, to chop off the witch's head. But Mogensen also soon got independent scenes with the soldier to draw and animate, and he actually got away with it quite well, even though his drawing and animation style seemed more naturalistic than the one the soldier's main cartoonist, Børge Hamberg, used. - Photo: © 1944 Ulf Nielsen / Politiken.

Here the soldier has fun with the Master Jakel dolls during his and his friends' visit to Dyrehavsbakken. The animation of the soldier clapping his hands was partly reused in the scene in the Royal Theater, where the soldier is at an opera performance, which by the way bores him. The soldier is also here drawn and animated by Mogens Mogensen and the middle character by Torben Strandgaard. The other characters in the picture are drawn and animated by Preben Dorst. The background is also in this case painted by Finn Rosenberg. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

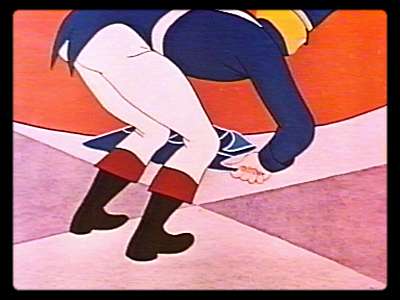

Another cartoonist who, as also mentioned earlier, drew and animated a few scenes with the soldier was Preben Dorst. It happened, long before he went on to animate the princess. But Dorst drew and animated e.g. the scene in which the soldier on his march along the country road is inadvertently stepping on a small worm, which, however, manages to escape.

Here is one of the few scenes that Preben Dorst drew and animated with the soldier. In the sequence to which the scene belongs, the soldier is on his way along the country road, and here it is that he is inadvertently stepping on a small worm, which, however, manages to avoid being trampled to death. The scene is in-between drawn by Arne "Jømme" Jørgensen. The background is painted by Finn Rosenberg. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Another of the scenes with the soldier that Preben Dorst drew and animated was the one in which the soldier is fired down into the witch's hollow tree. The soldier is drawn by Bodil Rønnow. The crow, which sits at the top of the edge of the hole and watches the soldier descend, is drawn and animated by Harry Rasmussen. The background is painted by Finn Rosenberg. Incidentally, the scene was reused when the soldier ascended, but in reverse order. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

On April 5, 1944, we heard in the drawing room that some saboteurs had broken into UFA's departments at the top of Nygade 3, where the offices had been emptied of papers and the fireproof boxes for a large quantity of German feature films, all of which were thrown down. the street where it was burned. Both papers and films were flammable and combustible, the films especially because they were explosive nitrate films that not only burned, but even exploded. But fortunately for Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S, they had neither exposed nor developed negative or positive films lying at UFA at that time. However, the saboteurs apparently did not have the time or the task of razing UFA’s Danish department further, and this was fortunate for the Danish staff who worked on site on a daily basis. But it was, of course, a great shock to all the staff, who were hardly more German-friendly than so many others in the population, that the conditions of the war suddenly came as surprisingly close as was the case in general. During the period when it was possible to see 'our' line tests in UFA's cinema at the laboratory in Nygade, it was the well-known and held Mrs. Edith Schlüssel in the film industry who cut the film strips together into a loop so that they could be run uninterrupted, until we had each made sure that the animation of the figure or figures was in order. The immediate consequence that the assassination attempt on UFA's Danish department had for us animators was that we could no longer see our line tests in their showroom for the time being. This circumstance meant that the control run of line tests was relocated to Nordisk Films Teknik in Frihavnen, which was much further away than Nygade 3. Therefore, only the management and the chief draftsmen were allowed to see line tests, and who could then report to the animators about the results of their efforts.

An interesting detail is attached to Gerda Holck Hansen's meeting with Allan Johnsen. The then 21-year-old Gerda had applied as a student at UFA FILM in Nygade in Copenhagen, and it was here that she and Johnsen met, as he had his regular run in the company. The latter was due, as already mentioned, that during the German occupation of Denmark it was only possible to buy 35mm raw film, especially color raw film, from the German company AGFA, and that the film material could only be developed and copied at this company's laboratories at UFA in Berlin. UFA Film in Nygade was therefore a communication link to the UFA laboratories in Germany.

Towards the spring of 1944, there were gradually a large number of larger and smaller sequences and scenes in working copy, and although these were not in all cases continuous according to the film's action, Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S 'management believed that time had to be in to acquaint the employees with the preliminary result of the many employees' work efforts and efforts. In the long run, it was unsatisfactory for most people to see only drawings, celluloids and backgrounds on a daily basis, without knowing what the purpose of it all was. The management would therefore now remedy this.

The first screening of "Fyrtøjet"

On May 20, 1944, something happened that was at least an event for all the employees at "Fyrtøjet". At that time, about a year after the actual production of the film had begun, Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S was in the happy situation that a special screening of the staff of about half of the film could be arranged, admittedly in dumb working copy. However, as they did not have their own film screening equipment, a screening was arranged at the nearby Grand Theater in Mikkel Bryggersgade. The theater was then run by the famous silent film director Urban Gad (1879-1947), and he was also present as host and welcomed the morning when the screening of the silent working copy of the recordings of "Fyrtøjet", which until then had been completed, took place. It was the first time any of the staff - apart from Johnsen, Finn Rosenberg, Peter Toubro, Henning Ørnbak and the chief draftsmen - had had the opportunity to see the result of the great work that many of them had been doing for about a year now. Even then, I had only seen line tests of some of the scenes I was an animator on. So I was at least as excited as everyone else to see the preliminary result in the form of the half-finished film, and even in color. Color films were a rarity at the time, when virtually all feature films, Danish as well as foreign, were in black and white.

At the time, I did not know exactly who and what Urban Gad was for a personality, but later I understood that he and his in a way fantastic pioneer efforts in Danish and German silent film, was something close to unique. As a personality, he, who in 1943 was 64 years old, seemed immensely quiet and modest in his appearance. But he could hardly have always been as dry and withered as he seemed in 1943, because in 1925-26 he wrote the script for and directed the film "The Wheel of Fortune" with the Danish comedian couple, Fy and Bi.

After the demonstration, which only took about three quarters of an hour, there was general agreement among the employees that the result of the great efforts, despite obvious shortcomings and errors, was largely acceptable.

On the same occasion, Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm had invited the entire staff to a dinner event in the Officers' Association's function rooms behind the Industrial Building on Rådhuspladsen, and afterwards a tour of Tivoli was offered. It was an enjoyable day with various rides for the more childish souls among the staff, and a very wet and humid trip for pretty much the entire creative part of the staff, from the oldest, Otto Jacobsen, to the youngest, Harry Rasmussen.

This photo is a snapshot from Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S ’dinner event in the Officers' Association's function rooms on 20 May 1944. The people are a little difficult to recognize in the somewhat blurry picture, but from the left Ms. Zotsi, Erik Christensen (Chris) and Mogens Mogensen. To the right, calculated from the back end, is seen just exactly the head of photographer Marius Holdt, then a non-identifiable person, then N.O.Jensen, Karen Bech and a man whose name I do not remember. I myself am seen at the very back on the right, as I am obviously on my way around the table. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Another situation from the dinner in the Officers' Association's premises. From left are Sven von Linstow, Torben Strandgaard, Henning Dixner, (probably) Preben Dorst, Mogens Mogensen, (probably) Alice Bitten Andersen, N.O.Jensen and Marius Holdt. On the other side of the table is seen (probably) Ms. Zotsi, an unidentified, Mona Irlind and Harry Rasmussen. At the far right is Allan Johnsen. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Here you can see from the left and around the table Preben Dorst, Alice Bitten Andersen, Allan Johnsen, Mogens Mogensen, Erling Bentsen and (probably) Bente Bentsen, Peter Toubro and Line Kofoed. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Here is the same dinner party seen from the opposite end of the table, where only a few in the picture are recognizable. From left is Mogens Mogensen, and on the other side of the table are seen from right Alice Bitten Andersen, Preben Dorst, Otto Jacobsen, unidentified lady, and also two unidentifiable: a lady and a man, the latter possibly Bjørn Frank Jensen, and at the very back Børge Hamberg. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Above you have reached the drinks. Sitting in the foreground is seen from the left (with her back to possibly) Line Kofoed, behind her an unidentifiable lady, Ms. Zotsi, and standing with his back to possibly Bente Bentsen. Standing from left unidentified lady, Allan Johnsen, unidentified gentleman, Otto Jacobsen and Sven von Linstow. At the very back in the middle of the picture is a small group of standing people, of which Børge Hamberg is seen with his back to and Mogens Mogensen in three-quarter profile. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

In this snapshot from the party in the Officers' Association's Banquet Rooms, Otto Jacobsen, Harry Rasmussen and Børge Hamberg can be seen from the left. It is clear that not only was there a big difference in size, but also in age between the two adult cartoonists and the then barely 15-year-old me. It is clear that at least I have had a little more to drink than was good. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Here, part of the 'house orchestra' from the design studio in Frederiksberggade has started to entertain those of their colleagues who were guests at the dinner in the Officers' Association's premises on the festive day in May 1944, where about the first half of "Fyrtøjet" earlier in the day was has been shown in the Grand Theater. From left, Torben Strandgaard is seen as janitshar, Erling Bentsen with guitar, Finn Rosenberg with violin and (probably) Henning Ørnbak at the piano. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Above, some of the party participants are about to leave the Officers' Association's Banquet Rooms after a good dinner, and possibly on their way into the nearby Tivoli. In the front row are Line Kofoed, Karen Bech, Henning Dixner, and behind these (with raised hat) Sven von Linstow, Behind this group is another group, consisting of from the left the little person, who is probably me, then Chris and the archivist "Bjørn", also called "Largo". In the background is a couple of unidentifiable people. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

In this photo, which was taken in Tivoli's Ferris wheel high above the garden trees, the two game makers, Chris and Harry Rasmussen, are seen, both of whom have obviously looked a little too deep in the glasses during the gala dinner in the Officers' Association's function rooms. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

To the left another situation from Tivoli's Ferris wheel. The picture is unfortunately a bit blurry, but it is Børge Hamberg who turns around and looks up at the photographer, who was sitting in the same gondola as Chris and Harry Rasmussen. To the right, a clearly influenced Børge Hamberg comes running out of the toilets at Tivoli's Main Entrance, waving his hands dry on the way out into the open. - Photos: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Let us end the discussion of the gala dinner and the Tivoli tour afterwards with this photo of two obviously intoxicated animators, the 23-year-old Chris and the only approx. 15-year-old Harry Rasmussen, who here is literally supported by Børge Hamberg, whose arm it is that you see protruding into the picture. - Photo: © 1944 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

In the following time the daily work on "Fyrtøjet" continued with renewed energy and a certain enthusiasm, which stemmed from the fact that the presentation in the Grand of the preliminary result was a little more than acceptable, despite the obvious shortcomings and errors, which in all fall the animators could see at the movie. Everyone as one hoped for and tensed up to do the animation etc. still better and more lively. By ability and experience of course. Incidentally, the biggest problem was that due to the production pressure, there was not much room to actually remake scenes completely. In some cases, therefore, one had to settle for a not entirely satisfactory result.

Plans for new cartoon projects

However, the presentation of "Fyrtøjet" had left a certain optimism, both among the management and the creative staff. And even though one could not immediately determine the time, one still began to think about what was going to happen after the film was finished. Allan Johnsen and Finn Rosenberg in particular, as well as the key cartoonists, were interested in the fact that the production of cartoons should preferably continue continuously, if it would be at all possible to finance such production. The idea of some state aid via the Ministries' Film Committee (MFU) was probably in mind, but to find out if it were a possibility, one first had to prepare one or possibly several suggestions for cartoons that could be considered to produce.

To this end, the management especially encouraged the animators to come up with such suggestions, and preferably with a synopsis, a design and some character drawings. It was agreed in advance that the topic or topics for Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S 'possible continued production should again be based on one or more of H.C. Andersen's adventures. It was especially the idea of several short H.C. Andersen fairy-tale cartoons that won attention, probably because immediately after "Fyrtøjet" they did not dare to venture into such an extensive and expensive project.

But in any case, there were six of the cartoonists who each made their own proposal for a short H.C. Andersen fairy tale cartoon. To now take Finn Rosenberg first, since he was the initiator of the feature film "Fyrtøjet", his proposal, as far as I remember, was a cartoon film adaptation of the fairy tale “The Swineherd” ("Svinedrengen"). Børge Hamberg suggested "Klods-Hans", Bjørn Frank Jensen wanted to make "Elverhøj". Preben Dorst characteristically had "The Princess on the Pea" in mind. Simon came up with a synopsis and glorious drafts of figures for "What the father does is always right", while I, Harry Rasmussen, suggested "The Emperor's new clothes". For the latter, I made some figure sketches, and Kaj Johnsen, who was a draftsman and colorist, painted an excellent background with motifs from the city to which the two deceitful tailors arrive, and where they make the king, the court and all 'sensible' citizens laugh.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to bring pictures from all of the above-mentioned and planned adventure cartoons, as such are either not available or have probably been lost in some cases. At least they are for my own party. However, it is possible to bring individual drafts from two of the planned cartoons, namely "Klods-Hans" (“Clumsy Hans” and "Elverhøj" (“ The Elf Hill).

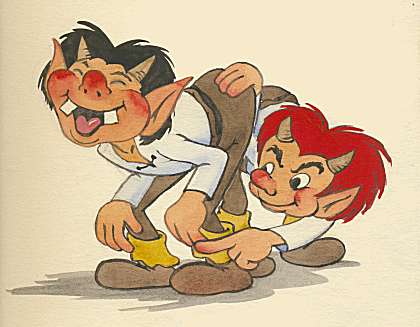

Here is a cheerful draft of the planned short cartoon about the fairy tale “Clumsy Hans” ("Klods-Hans"), which Børge Hamberg had proposed in 1944, when Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S had plans to continue the production of H.C.Andersen-adventure cartoon after "Fyrtøjet”. In 1948, the idea was taken up again, but now in the form of a new feature film, which Børge Hamberg once again became chief illustrator, without it being his character draft that was used in the pilot film that was made before the project was shelved. - Drawing by Børge Hamberg 1944. Donated in 2003 by Mrs. Gerda Johnsen to © Dansk Tegnefilms Historie.

Børge Hamberg's sketch draft for repeat animation of Klods-Hans’ goat. The sketch is from 1944 and was part of Hamberg's proposal for a short cartoon about H.C. Andersen's glorious fairy tale "Klods-Hans". - Donated in 2003 by Mrs. Gerda Johnsen to © Dansk Tegnefilms Historie.

Fortunately, I am in the situation of being able to bring a little more drafts, a total of four, of Bjørn Frank Jensen in connection with his proposal from 1944 to make Andersen's fairy tale "Elverhøj" as a shorter cartoon.

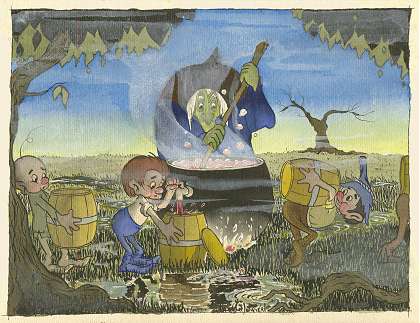

One of Bjørn Frank Jensen's drafts from 1944 for the adventure cartoon “The Elf Hill” ("Elverhøj"). Here it is Mosekonen (The Moor Wife) who brews, while the little troll children in turn each fill their barrel with her enchanting drink. - The drawing was donated in 2003 by Mrs. Gerda Johnsen to © Dansk Tegnefilms Historie.

Here is Bjørn Frank Jensen's draft from 1944 of what he thought Elverkongen (The King of the Elves) should look like, at least in the cartoon he had intended to make for Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S if the company's cartoon production was given the opportunity to continue after "Fyrtøjet". - The drawing was donated in 2003 by Mrs. Gerda Johnsen to © Dansk Tegnefilms Historie.

Bjørn Frank Jensen's character draft from 1944 for the two Norwegian troll boys in the cartoon "Elverhøj". The characters are obviously drawn in 'classic' - some might say traditional - cartoon style, but if you think of these animated in Bjørn Frank's solid and safe animation style, a quite good and enjoyable result could have come out of it. - The drawing was donated in 2003 by Mrs. Gerda Johnsen to © Dansk Tegnefilms Historie.

Bjørn Frank Jensen's draft character from 1944 of "The Drummers" for the cartoon "Elverhøj". The draft gives a small impression of how Bjørn Frank probably also intended the film's backgrounds to be performed. - The drawing was donated in 2003 by Mrs. Gerda Johnsen to © Dansk Tegnefilms Historie.

As you will be able to read about in the section "The cartoon "Klods-Hans", Allan Johnsen and Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S succeeded in 1948 in being granted money from MFU for a pilot film, which was to form the basis for a committee under Dansk Kultur Film could decide whether the cartoon project was of a quality and standard for which it was worth providing financial state support.

Speaking of Bjørn Frank Jensen, around this time an event took place, which came to touch him deeply unpleasant. At the design studio, as previously mentioned, there was a bidder named Erik Nielsen, who due to his appearance went by the name "Pluto" on a daily basis. He was a friendly and sociable person and at the same time very conscientious, although he was not one of the smartest. One day, when he had to transport one of the cardboard boxes with animated drawings and finished cells home to Frederiksberggade from the department on Nørrebrogade by tram, things went horribly wrong. It was very common at that time that the trams were so crowded that in order to get in at all, several passengers had to stand on the step boards and cling to the handles intended for that purpose. On that particular day, "Pluto" could only fit on the step board on a line 16, where he clung to the handle with one hand, while with the other he made sure to hold the relatively large cardboard box in to the body. The accident further meant that it was both rainy and windy weather that day, and as the tram swung from Vester Voldgade into Rådhuspladsen, "Pluto" lost its grip on the cardboard box, which fell to the ground, where the lid went up and all the animation drawings and celluloids fell out and was blown around and was scattered all over most of the square. And even though brave people tried to help him reassemble the now wet and damaged drawings and celluloids, he failed to get hold of the part that was blowing down Vester Boulevard (now H.C. Andersen's Boulevard).