“FYRTØJET”:

Palladium A/S steps in

As previously mentioned, in the autumn of 1944 there were probably around 40-45 people gathered in a room of the relatively small size, as was the case with the design studio at Frederiksberggade 28, which should only have constituted a workplace for a maximum of 20 people. At the same time, it was clear that even more employees would be needed if the already extended production time were to be met. Due to the gradually occurring and very noticeable lack of space, a large part of the middlemen and the entire drawing and coloring staff moved during 1944 to some rented premises in Nørrebro, partly above Nørrebro's Messe on the corner of Nørrebrogade and Blågårdsgade and partly to rented space. on the second floor of a factory property, called "Skræddernes Hus", in Stengade, which for several floors was arranged for sewing rooms. It was in connection with one of these, which was located on the second floor, that a lot of interpreters, as previously mentioned, got a permanent job for the rest of the production time.

The coloring department on Nørrebrogade soon became too cramped for the many new young and younger ladies. Other and larger premises were therefore rented at Nordisk Kollegium on the corner of Strandboulevarden and Willemoesgade, and the inking and coloring department was moved to this location. The latter department was continued to be headed by Else Emmertsen.

Even later, probably around February 1945, the department was moved to the property on Vesterbrogade, where the clothing company Westerby had a business on the ground floor. The drawing studio were on the top floor. About this workplace, Karen Bech alias Karen Egesholm can e.g. tell the following:

“Vesterbro. Then we moved again to premises at the top of Vesterbrogade, where the clothing company "Westerby" was in the living room. Here were studio windows and some ladies came and others went. We had ladies who we understood lived hidden. I think there were Jews and women who were part of the resistance movement. Mysterious telephone conversations took place. There were also people who were not affiliated with the company. For a period, Jenny Holmqvist replaced Else Emmertsen, who apparently was ill. Jenny Holmqvist was heavily pregnant at the time. We still had the ladies divided into groups and problems with the colors. […]” (Note 1)

As stated in Karen Egesholm's note, the drawing room on Vesterbrogade also became a daily hiding place for Jewish women, who had managed to avoid arrest on October 2, 1943 and in the time thereafter. In addition, it was allegedly also a hiding place for female members of the resistance movement, who apparently also used the design studio as a contact point with presumably illegal persons who had no direct connection to Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S. It was again Allan Johnsen's humanity and daring that was expressed here in the fact that he partly helped people to hide from the Germans, and partly worked in favor of the resistance movement. As previously mentioned, the same was also the case at the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28.

After the inking and coloring department had moved out to the Nordic College, a number of in-betweeners under the leadership of Bjørn Frank Jensen moved into the drawing studio on Nørrebrogade, while Mogens Mogensen became head of the in-between department in Stengade. Especially for the latter and quite special place, many new employees soon came because there was the best space in this drawing studio.

Although it was standard procedure during the production of "Fyrtøjet" that line tests of the animation were recorded, it occasionally seemed that line tests were found unnecessary and a waste of time. But in any case, I experienced for myself that some of the scenes I animated in the film were recorded on 35mm black and white negative film, so that one could judge whether the animation worked satisfactorily. However, the line test was not recorded on Holdt's trick table, but as far as can be remembered on the trick table out at Nordisk Films Teknik in Frihavnen. However, they did not have an editing board or display device at Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S at that time, and they therefore had to resort to places nearby where it was possible to watch the test film.

To begin with, line tests were run as previously mentioned by the American rental company Warner Bros. or MGM on City Hall Square, but after the Germans in the fall of 1943 effectively banned the showing of American feature films in cinemas, the offices of the American rental companies were eventually forced to close. As the film "Fyrtøjet" had to be included in the German color film system Agfa Color as a result of the war, and this 35mm film type could only be developed in Germany, more precisely at UFA's laboratories in Berlin, it was inevitable that the connection was linked to the film company UFA. This company had offices, cutting rooms and showrooms in Nygade 3, where by the way the cinema Nygade Teatret was located on the ground floor, and here a couple of us animators came occasionally, bringing the blunt line test film that had recently returned from black and white development in The Freeport. The film strip was now left to one of UFA's Danish film editing ladies, who glued its ends together into a loop, after which it was handed over to the operator and shown to us in the place's small cinema hall. The film loop was run as long as we found it necessary for us to determine if the animation was okay or if there was something to correct or add.

However, it soon came to an abrupt end to see footage of line tests. It happened, as previously mentioned, more precisely on April 5, 1944, as UFA's offices and premises on that date were razed by some saboteurs, who threw the company's papers and about 200 feature films down the street, where it was all ignited and more or less burned. The feature films were then still recorded and copied on the highly flammable nitrate material, which almost exploded upon ignition and developed a strong smoke in the few minutes it all burned. As a result, UFA's offices were temporarily closed until the premises had been renovated and made ready for use again. But after the sabotage, UFA's rental office in Copenhagen so far only had the feature films in stock that were out in Danish cinemas at the time of the attack, and which therefore did not suffer the same fate as the approximately 200 feature films that had been in stock but had become destroyed. (Note 2)

One might wonder why the animators were not given the opportunity to see their line tests at Nordisk Films Teknik in the Freeport, when it was even there that the line test was recorded and developed. I actually have no knowledge of or explanation for this, just as I cannot explain why Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm did not itself acquire either an editing board or a 35mm display device, a so-called Moviola, for the purpose. My guess is that during the whole production process the company was in a hard pressed financial situation, which was partly due to the fact that the budget was calculated too low, and partly that the production of the film actually went too slow to be able to comply with the production plan. One, which primarily means Allan Johnsen, probably considered it a waste of time that the animators should occasionally interrupt their work and spend time going forth and back to the Freeport, to see line tests. At that time, none of the staff, nor the director or the instructor, had cars available, and expenses for e.g. taxis were considered an unnecessary waste of money. Passenger transport therefore had to take place either on foot, by bicycle or by tram, and for some by S-train or regional train. The latter was also the case for Allan Johnsen, who commuted every day between his home in Gentofte and Nørreport Station. From there he strolled forth and back to his office in Frederiksberggade 10.

The director's dilemma

Director Allan Johnsen was generally respected by the staff, but with his somewhat private and reserved nature, he was not a boss who wanted to get his employees close to life. He belonged to the somewhat old-fashioned type of leader who always knew how to keep a certain distance, even to his most trusted employees, but his manner was mostly friendly and accommodating. Personally, however, I got the impression that he maintained a facade of unapproachability, in order to better manage and lead the many different kinds of people that circumstances had made him the leader of. Johnsen's reservations were probably also due in part to the fact that in his double situation as responsible for the operation of Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S and his illegal position as a resistance fighter, he had to whip himself into silence. This double situation probably posed a dilemma for him.

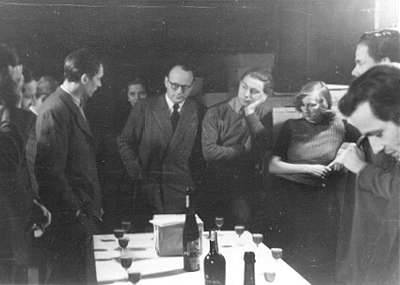

But that Allan Johnsen was, after all, held by most of his employees, one got the impression when the staff on the occasion of his wedding on January 19, 1945 with his secretary Gerda "Tesse" Johnsen, born Holck Hansen, the day after congratulated and celebrated him at the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28. That situation was maintained in some photos, which as usual had been taken by the house photographer Arne "Jømme" Jørgensen.

In this photo, which was taken on January 20, 1945 at the drawing studio in Frederiksberggade 28, is seen from the left Børge Hamberg, who is speaking for the newlywed Allan Johnsen, who is standing in the middle of the picture and listening. Far to the right in the foreground is the head of Bjørn Frank Jensen. Partly hidden behind Børge Hamberg, the neck of me, Harry Rasmussen, can be seen. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to identify the other people in the picture. - Photo: © 1945 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Photo from the same situation as above. To the left in the foreground is one of the police officers who had gone underground. His name was probably Lerche. Allan Johnsen is seen right behind the latter and in conversation with Bjørn Frank Jensen. Far left with his back to Peter Toubro is seen, and the lady at the top left in the picture is Ms. Zotsy. The slightly older gentleman in the background is the trick photographer Marius Holdt, who is standing by the wall into the trick room. Lady No. 2 from the right is Henny Hynne. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to identify the other people in the picture. - Photo: © 1945 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

Photo from the same situation as above. In the foreground are Bente Nielsson, Erling Bentsen and Harry Rasmussen from the left. The name of the gentleman on the far right is unknown, but he was also one of the policemen who had 'gone underground'. In the background are seen from left Henny Hynne, then two unidentified ladies, police officer Lerche, Else Emmertsen, unidentified lady, Mona Irlind (with glasses) and probably Ea Johnsen. - Photo: © 1945 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

But the days were of course especially marked by the work from kl. 8 a.m. to 11 p.m. On Saturday, however, work was only done until kl. 14, after which Bentsen-Band usually held a jam session to the great pleasure of the part of the staff who had the time and desire to stay and listen. It was usually only quite a few, and to these I belonged myself, as I especially liked the swing-like music that was played. It was soothing and relaxing in a time that was both literally and figuratively dark.

A few days after we at the drawing studio had congratulated and celebrated Allan Johnsen, we learned, more precisely on January 23, that many Danes' dear weekly magazine "Familje-Journalen"'s domicile out in Valby had been Schalburgtaged and almost completely destroyed. This meant that the magazine could not be published for the time being. In 1942, as a school student, I had been with my class on a company visit to the busy magazine factory in Valby, and it was impressive to see how my mother's dear weekly magazine was made from A to Z.

But otherwise the general situation in Denmark was not pleasant, because in the middle of the winter cold and darkness, the fuel situation became very serious, so austerity measures had to be introduced wherever possible, and for that matter also where it was not possible. From February 6, the temperature in residential and commercial buildings was not allowed to exceed 16 degrees Celsius, while cinemas, churches and meeting rooms were only allowed to be heated to 10 degrees Celsius. This meant that people had to wear warm outerwear, even when going to the cinema, to church or attending meetings. Tram traffic was reduced from February 1, and the same applied to the State Railways, partly in the form of fewer train departures and the cancellation of trains late in the evening. The rationing of the gas and electricity supply was tightened, as the previously barely allocated rations were further reduced by approximately 50%. Amusement establishments were to close at 20.30 and restaurants at 20.45, just as earlier store closures were introduced than usual. The radio broadcasts were to end at 21, supposedly to save power. But people could of course choose to listen to the foreign radio stations, if otherwise it was not made impossible by the German noise transmitters. But strangely, it was still possible for more advanced radio receivers to tune in to the BBC in London and listen to the Danish broadcasts from there. However, these only lasted from kl. 20 to about 20.30.

In fact, it got so far in Denmark that rationing of coffee substitutes, such as Rich’s and Denmark’s, which many Danes had otherwise become accustomed to as early as the 1930s, partly to save on the expensive coffee beans and partly to make the coffee more ‘full-bodied’. Probably as bad was the fact that there was a potato shortage, because potatoes actually belonged per. tradition for the Danes' daily dinner. The situation was not improved by the fact that in February the Germans started sending refugees to Denmark in increasing numbers, so that Copenhagen eventually housed around 90,000 and the whole country together close to a quarter of a million. Numerous buildings were seized to house the refugees, including schools, which meant students had to be lumped together and taught at other schools.

The large influx of refugees, which mostly consisted of women, children and old men, was due to the fact that the German cities had been almost bombed out, so that people had nowhere to live, just as the infrastructure had been destroyed and the lack of everything was appalling. Therefore, it was easy for the Nazis to send German refugees up to the 'dining room' Denmark. But the German refugees were a great burden to the country, and were therefore also laid for hatred, and after the capitulation, the refugees were therefore immediately removed from the seized schools and the like. and placed them instead of in refugee camps set up for that purpose. From here, the first teams of refugees were sent home to Germany from November 1, 1946, and the last team did not leave Denmark until February 1949.

But just as important was the fact that the sabotage actions of the resistance movement continued with undiminished frequency, despite the fact that many resistance fighters had been arrested, tortured and in several cases executed by firing squad. But it was mainly thanks to the efforts of the resistance movement that Denmark was at last perceived as a country that directly fought Nazism, and which the Allies could therefore consider with sympathy and a certain admiration. It also gained great importance after the end of the war and in the years that followed.

The production of "Fyrtøjet" ensured

It is clear that with the overtime on "Fyrtøjet" in general, more animation drawings and more celluloids would be made per working hours than if no overtime had been introduced. But since the working days became extraordinarily long due to the overtime, this in the long run also seemed tiring and exhausting to the employees. Gradually, therefore, this did not become as effective as the management must have expected or at least hoped for.

At the same time, it almost goes without saying that with the overtime introduced and the resulting overtime pay, the already tight budget was further burdened. It therefore soon became imperative for Allan Johnsen to make sure that new capital was added to the completion of "Fyrtøjet". But with the prospect of the film being completed within reach, one should also have an established distribution company to rent out "Fyrtøjet" to the cinemas. For good reasons, it was not Nordisk Film that Johnsen turned to, because he did not have good experiences with the management of this company. And ASA Film, or the few other Danish film companies of the time, were hardly strong enough to take on the task. Negotiations were - as far as I know in the autumn of 1944 - therefore instead started with the film company Palladium, which was both a production and film rental company, and which had a considerable film production behind it. Palladium was represented by the two experienced filmmakers, the brothers Svend and Tage Nielsen, and the negotiations led to this company becoming a co-producer and distributor of the film.

This ensured Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S as well as the continued production of the feature film "Fyrtøjet". The public became aware of this via an interview with film director Svend Methling in Berlingske Tidende. Unfortunately, the interview is known only from an undated clip, but the date must have been in the beginning of 1945:

"Fyrtøjet" as Cartoon

The first Danish all-night cartoon "Fyrtøjet" has now been completed. Then there is the editing and synchronization, which the film company "Palladium" after agreement with the producer, the newly formed company "Danish Color and Cartoon", has taken over these days.

After the Takeover, Palladium has turned to Stage Instructor Sv. Methling and asked this to undertake the final work.

I am convinced that the cartoon like Fyrtøjet has a chance as an export product, says Svend Methling to "Berlingske Tidende".

It will technically be made in such a way that it can be easily synchronized with foreign song and speech, so I think that it will be really cut over large parts of the globe.

It is, on the whole, my conviction that cartooning is the only area in which Danish film will be able to assert itself internationally after the war.

Apart from the fact that Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S was not a newly formed company, Svend Methling signaled with his quoted statement an extremely open-minded and positive attitude to the cartoon media in general and to the feature film "Fyrtøjet" in particular. However, synchronizing speech and song with the image side of the film was not quite as easy as Methling had apparently imagined and hoped. And although "Fyrtøjet" was versioned in several languages, it did not become the successful "Export Product", as Methling had allegedly thought. Nor did his conviction that cartoons were the only medium or area that Danish film would be able to assert itself in the international competition after the war hold true. At least not directly, and not unless you include Børge Ring's Dutch-produced and Oscar-winning cartoon "Anna & Bella" (1984). From a commercial point of view, Danish cartoons have not been able to assert themselves internationally in the years after the war and up to the present (2006). Nor, even if one includes both nationally and internationally probably the most successful commercial cartoon company in the history of Danish cartoons: A.Film. This company's first real and completely professional feature film "Help, I'm a fish!" was, as far as is known, not the foreign success one had expected and at least hoped for.

As far as the more artistic Danish feature film production is concerned, this has been dominated by Jannik Hastrup's gradually long and so far unique series of feature films. It is entirely professional cartoons that have performed well, both in the domestic market and to some extent also in the foreign market, mainly the European one.

But it was not true, as the newspaper wrote, that "Helaftens-Tegnefilmen" - Danish press consistently referred to cartoons of a playing time as "Fyrtøjet", i.e. 78 minutes, like an all-night movie - that the movie was "finished" at the time in question. "Fyrtøjet" was not completed until the late summer of 1945. The term "all-night film" was used several years later and with greater right on feature films of approx. 3 hours playing time.

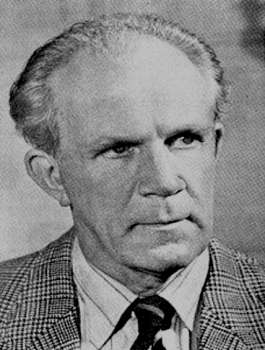

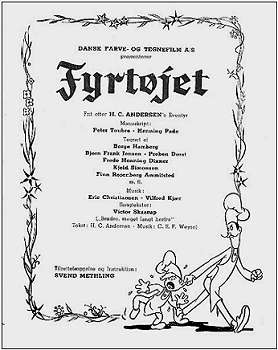

Theater and film director Svend Methling was hired by Film Company Palladium A/S to complete the feature-length film "Fyrtøjet", a work he began in early 1945 and which was not completed until the end of the year. - Photo from the film program for "Fyrtøjet": © 1946 Palladium A/S.

One can perhaps afford to ask the question what professional and artistic prerequisites, an admittedly experienced and skilled stage, short film and feature film director like Svend Methling had to take on such a special task as it was truly to "cut" and dubbing a cartoon like "Fyrtøjet". If you look at Methling's Filmography for the years 1938-44, it is not exactly cheerful films that dominate the list of films he directed. It was, on the contrary, grave films with historical and cultural themes as plots. However, a few comedy films had also been made, namely "Erik Ejegod's pilgrimage" (1943), "Dear Copenhagen" (1943-44) and "The Gelinde Family" (1944). The latter feature film was based on the author Mogens Lorentzen's novel of the same name, and it had premiered on September 26, 1944. The film had the special feature that there is a longer cartoon feature in it. This was produced by one of Danish cartoon's two nestors, Mik alias Henning Dahl Mikkelsen, who a month later was able to present his first independent short entertainment cartoon: "Ferd’nand on a fishing trip", which was produced by ASA FILM. (Note 3)

But in any case it was clearly a large, brave and risky investment on the part of Svend and Tage Nielsen, as there was no guarantee in advance that "Fyrtøjet" would at all be able to play its high production costs home by the economic standards of the time. However, in order to ensure that the film had at least entertainment qualities that could attract the audience, Svend and Tage Nielsen conditioned themselves first of all, that as already mentioned, a professional film director should be hired to lead the artistic side of "Fyrtøjet”'s completion, and secondly, that the soundtrack of the film became of at least as professional a standard. At that time, Palladium had a contract with the above-mentioned experienced theater and film director Svend Methling, whose previous feature films had had both artistic quality and audience attention. Therefore, the then 54-year-old instructor was hired as the main instructor on "Fyrtøjet". After all, something backwards, one has to say, as the majority of the film was produced at the time. But Methling was given the task, partly to edit the available film material, and partly to add scenes that he found necessary, so that a hopefully fairly solid and professional result could come out of the enormous work that had been put into the project since the beginning of 1943. In addition, Methling was to oversee the instruction of the actors who were engaged to record the dialogue, just as he was to combine this and the music. But it was of course not least from financial considerations that, at the instigation of the management of Palladium A/S, an experienced and knowledgeable film director was hired, as the film would like to play its costs home again, and preferably a little more than that. (Note 4)

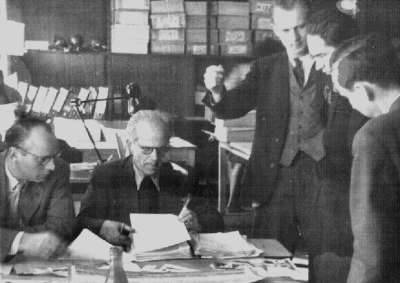

Above are seen from left Allan Johnsen, Svend Methling, Mogens Mogensen (with stopwatch), Børge Hamberg and Peter Toubro. The execution of a scene, which Børge Hamberg and Mogens Mogensen will probably draw, is obviously being planned. In the background to the left are the letter orders, which mainly contained delivery notes, and which 'archivist' Bjørn Jensen used to keep track of how far the individual scenes had come in production. At the top in the background are some of the many cardboard boxes, in which animation drawings, cells and backgrounds were partly stored, and partly transported back and forth between Frederiksberggade and the company's various drawing studios out in the city. - Photo: © 1945 Arne ”Jømme” Jørgensen.

The otherwise inexperienced Svend Methling, who took up his position as organizer / director early in the year 1945, began his work on "Fyrtøjet" by reviewing the large part of the film that had been made before he came to. He then quickly proved to be a committed and professionally competent director of the relatively few scenes he felt were lacking in order for the many, many scenes that had already been made to be coherent and promote the film's action plot in the best possible way. These scenes were drawn and animated during the spring of 1945. In connection with the editing work, it also became necessary to omit or shorten a scene here and there, as is usually always the case when editing films. But, of course, Methling had to make certain compromises, because for time and financial reasons he was not allowed to change much in "Fyrtøjet"'s long-planned action, sequence and stage sequences, which largely followed the script very closely, except for the valuable changes that Mik had proposed and which had long ago been made.

Among the few scenes that Svend Methling would like to add to the film were i.e. a couple of scenes with Bakken's Pierrot. He wanted an animation of Pierrot, where he eats burning tow and then blows smoke rings out of his mouth. These smoke rings would Methling use as a visual transition to a spinning lottery wheel in a subsequent scene. Pierrot was already designed and animated by Preben Dorst in 1943, but he had enough to draw and animate the many scenes with the princess. To my great surprise, it was therefore me who was appointed to draw and animate the additional scenes with Pierrot, and I probably got away with it quite well, considering my age and relatively little experience. Svend Methling was also a very friendly and pleasant person to work with, and full of humor and spirits.

At that time, it was just about to ebb out with animation tasks on "Fyrtøjet" for me, as all scenes with the witch, the crow and the smallest of the dogs were fully animated. But during his review of the very large part of the film, which was already in working copy, Methling thought that some scenes were missing in the sequence out on Dyrehavsbakken. "It must be something for you to do!", He came and said to me one morning, shortly after he had been hired as director and organizer of the film. That he addressed me with "you" was quite unusual at the time, but since he could easily have been my grandfather, it actually seemed very natural to me that he did, and moreover it felt safe and confidential. "I would like," he continued, "that you draw Pierrot, his hand in a close-up taking the burning tow from a bowl, and a semi-total picture of where he puts the tow in his mouth and eats it, to finally blow some smoke rings straight out in front of the audience so that these rings can make the transition to the spinning lottery wheel! ”

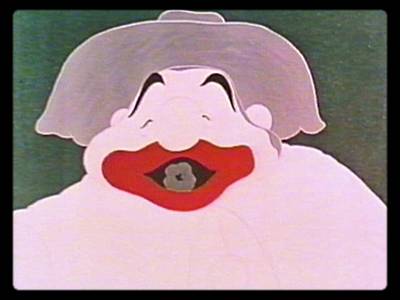

The first picture shows Bakken's Pierrot in a scene drawn and animated by Preben Dorst. Then a close up of Pierrot’s hand is seen taking the burning tow, in the third picture he puts the tow in his mouth and 'eats' it, after which in the fourth picture he blows smoke rings out towards the audience. The smoke rings were used as a visual transition to a scene with a spinning lottery wheel. The last three scenes are the layout, animated and in-between drawn by Harry Rasmussen. Backgrounds: Finn Rosenberg. - Photos from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

It was an interesting task to draw and animate Bakken's Pierrot, but I do not remember how long it took me to animate the mentioned scenes. However, it has hardly taken more than a week.

Another deposit scene, which Methling wanted made, occurs in the inn, where the soldier comes home late after spending all his money on the 'friends', and the innkeeper therefore refers him to the attic chamber. Methling wanted to show the time, and it was to take place using a cuckoo, which showed at. 2. Also this scene was left to me to draw and animate and Methling said he would give me completely free hands. Normally, the cuckoo would come out on the blow and in this case cuckoo twice, and then disappear in behind his gate again. However, the idea came to me, first to let the cuckoo come out after the long pointer was on full and the small pointer on 2, but without any cockroach being heard. It was because the cuckoo bird had slept over it. It rubs its eyes and looks at the clock, after which it, a little confused, hurries to hand over its delayed cuckoo, cuckoo. Then I let the double door into the cuckoo's hide close before the bird had reached inside, so that it was almost pushed back in through the double door. I and several others, including Allan Johnsen, thought it was funny, but Methling found that the latter 'gag' disturbed the action unnecessarily. Therefore, he cut off this part of the scene, which I thought was perfectly fine, as I well understood that Methling's task was to keep the whole film in mind.

Above are four situations from a scene that occurs in the sequence in which the soldier has arrived at the inn. The cuckoo shows at 2 night, and a little late and asleep, the cuckoo bird comes forward, rubs his eyes, looks at the dial and then hurries to cuckoo the specified two cuckoos. - The scene is designed, drawn and animated by Harry Rasmussen. The background is painted by Finn Rosenberg. - Photos from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

“FYRTØJET”: Recording dialogue and music

Svend Methling's greatest effort in connection with "Fyrtøjet"'s production, however, was undoubtedly the selection and instruction of the actors who were to record the film's dialogues. Unfortunately, this demanding process, which in this case had the character of post-synchronization, was only fairly successful, as the actors had difficulty recording the dialogue, so it became optimally synchronous with the animators 'unfortunately not too successful timing of the characters' mouth movements. This must not be said to be the fault of the director, actors or animators, but was due to the fact that the management from the beginning had intended to save both time and money by waiting to record the sound until long after the animation was made. With the Snow White film in particular, experience had been gained that the dialogue could very well be re-synchronized, even with a very good result as a result. However, it was overlooked that the original American dialogue of the Snow White film had been recorded before the animation began, and that this was a major reason why it was so relatively easy to make a Danish dialogue version.

The reason why one e.g. at Disney from the very beginning has always followed the procedure of recording the dialogue in advance, is primarily that this can subsequently be measured up and marked in vowel and consonant sounds, converted to x number of images on the photo list. On that basis, the animators can therefore draw and time the characters' mouth positions and other movements, so that both parts fit perfectly with each other at best. Moreover, the way in which an actor characterizes a character through the utterance of his remarks can greatly help to inspire the animator during the work of drawing the so-called key-poses. This is usually done in recent times by the lines of a scene being re-recorded on an audio tape, which the animator can regularly listen to during his animation of the character in question. But apart from that, this approach was and is the standard procedure in all professional cartoon production, and has been for many, many years, also here in Denmark.

But with regard to the sound recording for the feature film "Fyrtøjet", the audience was regularly kept informed via larger or smaller notes in the daily press about how far the production of "Fyrtøjet" had reached, and during 1945 especially about which actors should put voices to the various characters of the film. At one point, the press thought that Mogens Wieth should voice the soldier's voice, but that was not to be. An undated and unspecified newspaper clipping can, among other things. tell the following:

[…] Incidentally, there has now been talk for a couple of years about the large Danish H.C. Andersen cartoon, which is built over the fairy tale "Fyrtøjet", but so far it has been impossible to get information about when it will ever be finished. Now, however, it seems to be getting serious, as Karen Poulsen and Poul Reichhardt on Saturday were engaged to record the lyrics on "Palladium" in the roles of the witch and the soldier, respectively.

This photo shows the composers Vilfred Kjær and Eric Christiansen, who partly composed the beautiful background music and partly the beautiful melodies for the lyricist Victor Skaarup's beautiful lyrics. - Photo from the film program for "Fyrtøjet": © 1946 Palladium A/S.

In this unfortunately somewhat blurry photo from the recording of dialogue and song for the cartoon "Fyrtøjet", seen sitting on the left Svend Methling, and standing in front: Kirsten Hermansen and Poul Reichhardt. The sound engineer in the background is probably Palladium's sound master Erik Rasmussen. - Photo from the film program for "Fyrtøjet": © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Towards the year 1945, a rather small and unfortunately undated newspaper note could report:

PALLADIUMs editorial collaborator Miss Edith Schlüssel, has traveled to Paris to put the finishing touches on the editing of the great Danish cartoon "Fyrtøjet", which is now - at long last - being completely finished.

Shortly afterwards, Berlingske Aftenavis in the section "… i Forbifarten" By Per Haps, could report the following:

After an almost insurmountable series of difficulties have been cleared aside, the first Danish full-length cartoon will soon be premiered. It is a man relatively unknown to the public who is the producer, namely Allan Johnsen, who has worked tirelessly for a couple of years to get this film out. And at least he is not afraid, as it will be the most expensive film ever brought to market. According to what one of the initiates tells me, when the film is first rolled out, the producer will be worth ¾ million Danish kroner, a considerable amount, considering that it usually costs around DKK 200,000. to make a Danish film.

I myself have not seen the Danish cartoon, which is a re-creation of H.C.Andersen’s "Fyrtøjet", but a very experienced filmmaker who has had the film shown, says that it is an excellent film and that he is fully and firmly convinced of, that despite the large sums of money put into it, it will still come into play. He is so sure that he has entered into a very large bet with the producer, who now only hopes that he will lose the bet.

It is intended that the Danish cartoon, which is currently in Paris to get the final technical refinement, will have its premiere in the month of March in Palladium. It will be interesting.

As can be seen from the small note stated above, it was as we already know the experienced film editor Edith Schlüssel, who was in charge of the practical work of negatively editing "The Lighthouse", but of course under Svend Methling's expert guidance. As his assistant got Ms. Schlüssel the previously mentioned and then only 20-year-old Henning Ørnbak (1925-2007), among friends and work colleagues called "Pilatus". He had just become a student in the spring of 1944, and when his uncle, Robert Møller, was a shareholder in Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A / S, the young cartoonist Henning Ørnbak was employed by the company. Here he began as a colorist and draftsman, and later became an intermediate draftsman. After all, this job was not just for him, so instead he soon became a production assistant for Allan Johnsen. Years later, Henning Ørnbak made a career in theater and film, and you will be able to read more about this in the biographical section of this dissertation, and also in Krak’s Blå Bog, as well as in Filmens who - is - who 1957 and Filmens Hvem Hvad Hvor - Danish titles and biographies 1929 - 1967. (Note 5)

As previously mentioned, it has been claimed by the ignorant side that there was no script for the feature film "Fyrtøjet", a claim which now deceased Henning Pade on his own and Peter Toubro's behalf in his time was most surprised to hear. It looked so much more like it was Peter Toubro and himself who, assisted by Finn Rosenberg and Allan Johnsen, had written an even more detailed screenplay for the film.

But as far as I knew, there were only a few copies of the screenplay for "Fyrtøjet". Johnsen, Toubro, Rosenberg, Hamberg and Bjørn Frank each had a copy, and I do not think there were more. That is, there was an extra copy, which a short time later in the production process was left to the company's "archivist", the very young Bjørn Jensen, whom the colorists called "Largo". He was, as previously mentioned, through most of the production for the extremely important job of registering how far the individual scenes and sequences had come in the production process. With the help of his two bidders, he also arranged for the expedition of the animation drawings for intermediate drawing, drawing, coloring and later photography, and even later for archiving. Toubro usually went with his own copy of the screenplay under his arm when he stayed in the drawing room and conferred with one or more of the above about who should draw what and when. So also it was planned and determined in advance.

The fatal consequences of the war…

Karen Egesholm alias "Miss Bech", who was an employee at "Fyrtøjet" during the entire production period, was in February 1945 followed by the inking and coloring department's move to some premises at the top of the property on Vesterbrogade, where the clothing company Westerby had business on the ground floor. She tells about this:

[…] Here we experienced the bombing of the Shell House. It was violent up there under the roof. There were apparently some windows and everyone fled down to the yard, where there was a shelter. There was a lock off and no one had a key. We stood down in the shaft and heard the bangs, now probably from the French School and Maglekildevej. A girl fainted. When it was over we went home. Irmelin, who lived in Brønshøj, and I, who lived in Frederiksberg, followed Vesterbrogade and Frederiksberg Allé. Here we saw what had happened. We walked along the cemetery on the opposite side. My later husband, who at the time was a young firefighter with the Frederiksberg Fire Brigade, has later told about the horrific experiences they had with rescuing and driving away live and dead nuns and children on the spot. These are experiences you never forget and which are also connected to our time at "Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm". In my recommendation, I see that I have been employed until November 16, 1945, so we have probably continued in Vesterbro until the time when the work is finished. (Karen Egesholm in a letter dated October 20, 2001 to Harry Rasmussen).

March 21, 1945, was until about noon one morning, more precisely until about noon. 11, like most other preceding days. We were, as usual, met at work at 8 in the morning and was sitting in the middle of the work, when suddenly there was an infernal and hollow roaring sound, which was amplified by the relatively narrow courtyard shaft between the buildings in Frederiksberggade 28. Then we heard a series of thumping sounds a little further away, which we soon found out came from the Germans' anti-aircraft firing position on the roof of Dagmarhus. Some of us immediately rushed to the large window facing the courtyard, but by then the cause of the sound had long since passed. It came from one of the fighter jets from Royal Airforce, which accompanied the bombers, as they strode across the city on their way to the goal, which was to drop their bomb load towards Shellhuset by Kampmannsgade.

The Shell House, which was - and after later reconstruction still is - located on the corner of Vester Farimagsgade and Kampmannsgade, had been seized by the Germans at the end of February 1944 and arranged as the headquarters of the Gestapo. Here, third-degree interrogation and gross torture of arrested Danish resistance fighters took place, and as a kind of 'protection measure' against possible airstrikes, the Germans had very cleverly arranged the roof of the five-storey building with a number of prison cells, where particularly significant prisoners were placed. Therefore, it was fortunate that the English had trained the pilots to fly in from low altitude and throw the bombs towards the side of the house at about the second to third floor altitude. This part of the operation proceeded fairly according to plan, as several of the prisoners, who were prominent members of the Danish resistance movement, managed to escape.

The shell house burned out almost completely, leaving a smoking ruin, the smoke of which mixed with the smoke from the neighboring properties, to which the violent fire had spread. A number of prisoners as well as about 100 Gestapo people died as a direct result of the airstrike, but prominent prisoners such as Professor Mogens Fog and editor Aage Schoch, survived thanks to a brave police assistant who found his way out through the burning building, while others managed to escape to the undamaged part of the facade and from there venture the risky jump down the sidewalk. Fortunately, the rescuers were quickly brought away from the scene and to safety, presumably by newcomers from the resistance movement. Later, the survivors were able to tell that shortly after the attack they had succeeded in persuading a stunned German prison guard to unlock the cell doors so that the prisoners could escape and try to find opportunities to save themselves and their fellow prisoners in relative safety.

While the attack on Shellhuset itself had to be described as a successful precision work, the action had some very unfortunate and unfortunate consequences, partly because one of the English planes crashed into Fælledparken, and partly - and of course especially - because another of the planes during the approach over State Railway’s terrain hit one of the light masts at Enghavevej and was so damaged that it was not possible for the pilot to fix the plane again. It crashed right next to the French School, also known as the Jeanne d’Arc Institute, on Frederiksberg Allé, where the plane’s bomb load exploded, sending flames and smoke high into the air. The pilots of the accompanying planes perceived for a split second that this was the bomb target, which is why they dutifully emptied their bomb loads over the site - with catastrophic consequences for both people and buildings. Partly for the children and nuns in the French School, where 86 children and 13 adults died, but also for several people in the surrounding residential area: Sønder Boulevard, Henrik Ibsen’s Vej, Amicisvej and Maglekildevej, which were also hit by bombs. Some were killed while others became temporarily homeless.

The actual air strike came so surprising to the Germans and the Danish civil defense that they did not even manage to start the sirens, which should have warned the population. And also for the Copenhageners, the action came as a huge surprise, because one could hardly believe that such an attack would be possible. But the joy of the annihilation of the hated Gestapo headquarters was undeniably mixed with the unintended consequences of the attack.

A few minutes after we had heard the loud bangs after the bomb explosions over in the Shell House, "Largo" and I ventured down the street and onto the Town Hall Square, where everything was strangely abandoned and quiet. There were almost no people or traffic in the large square, which, on the other hand, was filled with shards of glass and office papers that had apparently been sucked out as a result of the bomb blasts about 5-600 meters away. Largo and I continued past Dagmarhus and along Studiestræde and over to railway track by Hammerichsgade, from where there was a clear view of the burning Shell House. However, this was not to be seen for the violent, black smoke that surrounded and rose from the burning building. There were also almost no people to be seen at the site, except that one could glimpse the firefighters, who were in the process of trying to extinguish the flames that were still blowing high into the sky.

It was an eerie and sad sight, even though we knew that the Shell House was the headquarters of the most hated and infamous part of the German occupation of Denmark, namely the Gestapo. None of us had anything left for these sadistic beasts, on the contrary, we wanted them to where some of them had now surely ended up, namely in a burning flame hell. But of course we also knew that there were civilian Danes employed in the house, i.a. office ladies who involuntarily presumably followed their employers to death.

The same evening that the bombing of the Shell House had taken place, one of my comrades and I drove the tram out to Frederiksberg Runddel, where we got off. Here we took cutlery from the situation, but dared to venture down Frederiksberg Allé and towards the French School, where the fire was still smoldering and firefighters were still guarding the place. However, the avenue was cordoned off some distance from the burnt out and collapsed school so we could not get close to the site. We then decided to walk behind one of the side roads and down to Frederiksberg Allé, approximately directly opposite the French School. Here there was a barrier at the end of the road so we could not get out on the alley itself. But apart from the smokescreen which had enveloped the place itself and the surrounding roads, and which still rested everywhere, there was a relatively unobstructed view of the sad ruins of the school. There we saw firefighters walking around keeping an eye out that the embers after the violent fire should not flare up again. Here and there they poked with iron rods to places in the ruin heap where the smoke smoldered. But fortunately the weather was calm, and this was further emphasized by the total silence that rested over the place, almost like in a cemetery, which in a sense it was, considering the many children and adults who died.

The unfortunate bombing of the French School, which was exclusively for girls, became one of the most tragic events of the Occupation Period, and the deceased pupils and teachers, all of women and teachers nuns, have been commemorated at a ceremony every year since the anniversary ever since. The school was not rebuilt, but a monument has been erected in memory of the deceased. The Royal Airforce pilots who took part in the fatal attack that fateful day and who have survived have been guests during the memorial service several times, as they as individuals were at least as affected by the unfortunate events as relatives of the deceased.

But in the midst of all the grief and sorrow, one should not forget that there were also many of the students and several of the adults who survived the eerie day of the year of liberation 1945. Several of the girls as adults have been able to tell about what they experienced and how they despite confinement in the burning buildings were rescued. Among these was one of my sisters-in-law, at the time mentioned 5 years old, who occasionally, when the talk fell on the time, could recount her own tragic experiences of mutilated and dead comrades. But here is not the place to go into detail with such accounts. In addition, life should, as always, go on, and here too we must go on with the somewhat more encouraging and enjoyable account of events in the history of Danish cartoons.

But it is understandable that in the days after the sad events, there was a somewhat depressed atmosphere among the Copenhageners, and not least with us at the design studio. A mood which, moreover, was amplified by the fact that in the following days we could see from the drawing-room windows the strange sight of horse-drawn carriages with open cargo, covered with tarpaulins, which, however, did not quite manage to hide the carriages' eerie cargo of a pile of charred human . A coal-black arm protruded here, an equally black leg there, so there could be no doubt that it was about the unfortunate dead after the bombing of the Shell House, especially not when the cars came from there and via Axeltorv, Jernbanegade, Rådhuspladsen and Frederiksberggade continued along Strøget over Kgs. Nytorv and Bredgade to Kastellet.

It looked peculiar with these needily covered horse-drawn carriages, pulled by a single horse and with a lone German soldier as rider, who sat motionlessly sunk in his seat with the reins in one hand and a long whip in the other. It was like a picture on death's postal carriage, which had picked up its 'harvest' of the recently deceased, and was now on its way through a heavily trafficked and crowded Strøget, to get the unrecognizable dead bodies out of the way.

Incidentally, the resistance movement perceived the air attack on the Shell House rightly or wrongly as a signal, partly that the Danish Freedom Council in London had influence, and partly that the British now regarded Denmark as an ally. The events of the next month and a half should prove to be of crucial importance to Denmark and the Danes. No one or only a few were any longer in doubt that the days of the occupying power were really numbered, but as you know, there is often a strong cold before the weather turns into spring. March is the month when cold and heat really take hold of each other, and best as it seems the coldest in the air, snowdrops and winter aconites peek out of the soil and herald the coming of spring.

“FYRTØJET”: The end

After about 2½ years of intense work, including several months of overtime with a working day of 15 hours, the management and employees in the spring of 1945 could begin to see that the end was slowly coming within sight.

There was a tense and at the same time somewhat dull atmosphere in the design studios, and not least in the design studio in Frederiksberggade, where all key animators at "Fyrtøjet" worked, except Bjørn Frank Jensen, who was head of the department on Nørrebrogade, and Simon, who was 'gone underground'. The depressed mood was partly due to the after-effects of several months of overtime, and partly to the fact that the intense work over time had become routine. The animators - and probably other employees as well - looked forward to the end of the demanding and somewhat one-sided drawing work at the light desk, and either to an upcoming summer holiday or to completely stop and team up with something completely different. But not least, the management, led by Allan Johnsen, with a certain nervousness and excitement looked forward to whether they could comply with the agreements with Palladium.

During this time, Allan Johnsen was seen less and less often at the design studio in Frederiksberggade. He presumably stayed away because he could hardly help but notice that some of the characters were actually behaving hostilely towards him when he appeared. However, it has hardly touched him particularly deeply personally, but he has probably realized that the situation was so sensitive and tense that he did his best not to show up too often. For him, it was first and foremost about promoting production as much as possible, so therefore he had largely left the 'control' of the design studio to Peter Toubro. Incidentally, it was my very clear impression that animators and other staff pretty much all did their utmost and best and worked as fast and efficiently as it was possible under the given conditions for each one to do. Most of them had realized and understood that they were participants in a very special and unique project, namely Denmark's very first long cartoon, which was also based on one of the world-famous H.C. Andersen's most famous and popular fairy tales.

The various animators and their assistants now worked on the very last scenes for the film, while an animator like Bjørn Frank Jensen, who had already finished the scenes he had been responsible for, went on to produce drawings with characters and situations from "Fyrtøjet" the film, partly those that were to be used in advertisements for various products, and partly those that were to be printed in the upcoming film program for "Fyrtøjet".

In addition to the front and back of the film program for "Fyrtøjet", Bjørn Frank Jensen also drew a number of character drawings as vignettes in the program. Above, it is the film's royal baker who pulls away with his naughty student, the baker boy, by the ear. - Page 2 from the film program for "Fyrtøjet": © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Here you can see the middle pages of the film program with various scene images and Bjørn Frank Jensen's vignettes with well-known characters from the film. - Middle pages from the film program for "Fyrtøjet": © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Another example of Bjørn Frank Jensen's character drawings in the film program for "Fyrtøjet". Here it is the king and the innkeeper who toast with each other. - Drawing from the film program for "Fyrtøjet": © 1946 Palladium A/S.

Above are two examples of some of the drawings with figures from the feature film "Fyrtøjet", which Bjørn Frank Jensen was master of. In this case, it's ads for ILKA Razor Blade that are no longer on sale. - Advertising drawings 1946: © Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S.

That time inevitably also came when Svend Methling also had no more deposit scenes for me to make, so therefore I actually became more or less unemployed. But at the time, it was so lucky that Otto Jacobsen would like to have a relatively experienced artist draw the scenes with the horses strapped in front of the bridal carriage. His choice fell on me, which I kind of felt honored about, especially since I thought he drew horses almost as well as my father had done in my childhood. My father was originally a farm worker and knew everything about the animals he dealt with on a daily basis, and he often drove a horse-drawn carriage with a two-bucket. In addition, as a trained and experienced rider, he had been a corporal in the Garderhusar regiment. So I felt like 'at home' with Jacob's horses. However, there was only work for a small week's time, so I gradually began to get impatient after something crucial had to happen in my situation. I mentioned this to Børge Hamberg, who, however, advised me to look at the time so far.

It was undeniably a somewhat strange situation to be in, not knowing what to do after two years of intense full-time work, including about half a year of overtime at "Fyrtøjet". Børge Hamberg suggested to me that I could continue to paint cells when there was no more drawing work for me. He reasoned that I, like himself and several of the other animators, could stay in the company and wait for a new production to be launched. He did not mention anything about which cartoon could be in question, but later I understood that there were already plans to translate Børge Hamberg's previous proposal for a cartoon about H.C.Andersen’s fairy tale “Clumsy Hans” ("Klods-Hans") for a longer cartoon similar to "Fyrtøjet". But even if I had known, I do not think it would have tempted me to stay, for the thought of having to sit all day and paint cels did not get me very well. In addition, I had other plans for my own future.

The fall of the tyrant

April 30, 1945 was one of the turning points of the war, for on this day, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler committed suicide in the Driver's Bunker in Berlin. He had gradually had to realize that the battle had been lost for das grose Vaterland, and in his cowardice he chose, in common understanding with his girlfriend Eva Braun, whom he, however, allowed himself to be married shortly before, to first let her commit suicide by swallowing a cyanide potassium pill, and then he shot himself through the mouth. It was the soldiers of the Red Army who, as the liberators of Berlin, reached the bunker, only to find that the formerly powerful German "Commander" was no longer alive. They found only a few charred corpses, which were thought to be Hitler and Eva Braun. Before his death, Hitler had ordered his adjutants that his and Eva Braun's bodies be sprinkled with a flammable liquid and cremated. As a result, the corpses became severely charred and unrecognizable, which soon gave rise to imaginative guesses that it was probably not Hitler who had been burned, and that he was therefore escaped and still alive.

On the basis of later documented information, however, it must probably be considered a fact that both Eva Braun and Hitler committed suicide and that both bodies were immediately burned outside the Driver's Bunker. But it is a fact that the newspapers' leaflets announced the same afternoon that Adolf Hitler was dead, and the details and details could be read in the newspapers.

Prior to Hitler's suicide, among other things, American troops had invaded Germany from the south, the British from the west, while the Red Army continued its invasion from the east, and as early as April 20, Berlin had been besieged and besieged. Moreover, both the Americans, the English, and the Russians had reached and had 'liberated' the concentration camps, where they were met with an eerie sight of starving and in many cases dying prisoners who had only been waiting to be killed in the gas chambers, and dead prisoners if corpses were piled up in heaps, to be burned in the crematorium furnaces. As early as February 19, Hitler had issued an order that all prisoners be killed and burned before Allied troops approached. Fortunately, this was not achieved, in part due to the fact that the otherwise so cruel and cynical Heinrich Himmler, who saw himself as Hitler's deputy, chose not to follow Hitler's order, not for human reasons, but only to appear if possible. in a better light than the Driver. At that time, Himmler had begun negotiations with the Swedish Count Bernadotte, in the hope of achieving separate peace with the Western powers. One of Himmler's means of pressure was, as previously mentioned, i.a. the captured members of the Danish police force in the Neuengamme Concentration Camp.

When the Allied soldiers opened the doors to the crematoriums, they saw to their dismay completely or only partially cremated corpses, and the piles of ashes spoke their own silent language about the fate that had befallen many, many completely innocent people who had simply become scapegoats for Hitler's insane racial theories and hatred of all the peoples whom he considered "subhumans".

It was under the impression of these events that Hitler had inevitably had to acknowledge that the power and time of his and his regime were irrevocably over. His great visions of a Nazi millennial empire had been put to shame in the ruins of German cities, which were the result of intense and month-long Allied bombing raids. The humiliation of the formerly proud Germany and German people on May 4, 1945, was as great as it had been twenty-seven years earlier, when Germany of that time had to acknowledge its military defeat and sign a peace treaty, which meant great deprivation for the coming Germany. On that date, German officers in Field Marshal Montgomery's headquarters at Lüneburg Heath signed the capitulation declaration for the German troops in the Netherlands, Northwest Germany and Denmark.

The hour of liberation

On the evening of May 4 at 20 had many Danes, as usual, set the radio's wavelength in London, from which the well-known voice of the Danish speaker, Johannes G. Sørensen, was heard saying: "One moment!" and shortly after: "It is at this very moment that it is announced from General Montgomery's headquarters that the German troops in Holland, Northwest Germany and Denmark have surrendered! I repeat, it is being announced at this very moment, etc. ” - With lightning speed, the incredible news spread in Denmark. In the streets of Copenhagen, people immediately opened their windows and turned on the BBC, so that the message of freedom sounded in the streets, where people immediately gathered, jubilantly happy and euphoric about what they heard from the radio and hardly dared to believe. Copenhagen was almost in revolt with joy over what had happened, and scenes unfolded that were not part of everyday life. The otherwise so cool and reserved Danes embraced and kissed each other, regardless of whether it was someone they knew or not. And the streets were full of people, just as people crawled up on top of the trams, which of course was not usually allowed. Everyone cheered and shouted loudly and sang with joy, and for many, the celebration of the message of freedom continued well into the wee hours.

However, the message of freedom was not equally welcome everywhere, and of course especially not with the occupying power, which suddenly had to see itself put out of the game. This probably also applied to a large extent to the Hippos and other peoples who had been more than willing to cooperate with the Germans, including the so-called defenders. Immediately after the message of liberation sounded, the streets almost swarmed with armed freedom fighters who were recognizable on their black steel helmets and a special armband. These so-called “4. May freedom fighters”, who to the surprise of many had open-loaded trucks at their disposal, immediately set about tracking down and arresting people who were known to or simply suspected of being collaborators or “field mattresses”, i.e. women who were thought to know that they had had sexual intercourse with the enemy. The detainees were taken under sharp guard to central collection points, such as schools where they were temporarily detained until they could be questioned and brought before a judge.

During the search and arrest, the freedom fighters often received help from civilian Danes, and when a man or woman was finally found who was suspected of having been in the service of the Germans, they were often directly exposed to the spectators' angry shouts and saliva. During this, the detainees were more or less brutally chased up on the barn by a truck, where they had been ordered to stand upright and with their hands folded behind their necks. Of course, it was tricky for those concerned to stay upright when the more or less loaded truck suddenly set off and drove away. Below, people came on the streets with loud shame-shouts and clenched and shook their fists at the suspected traitors. In some cases, one could even hear people's anger against these manifested in shouts, such as. "Cluster him up in a lamppost!" It also happened that a short trial was carried out against some suspected collaborators, as they were executed on the spot, allegedly because they had set themselves up as strong opponents or had tried to flee.

But all the more unpleasant and dark sides of the liberation days drowned in the absolutely fantastic and almost euphoric atmosphere that had spread among quite ordinary Danes, who usually did not dream of doing a fly harm. In the long run, peace would mean a return to so-called normal times of peace and order in society, and abundant food in the shops again, even if the rationing continued for some more years. In addition, it meant the resumption of imports of the many luxury goods that we Danes had been used to before the war, but had had to do without in the five damned years. It was goods such as textiles, petrol, coal and coke, etc., and coffee, tea, chocolate, bananas, oranges, lemons and much more and more, which, however, were still rationed in the first post-war years.

But an equally important international event was the creation of the United Nations (UN), in the form of a pact between the then 50 countries, whose governments signed the pact on June 26, 1945. Norway's first Secretary-General was elected Norwegian Trygve Lie. But even then it turned out that there was great disagreement between the various countries, and especially between the great powers, who had difficulty living up to and adhering to the ideals that the UN was supposed to guarantee and realize. It had failed for the League of Nations, but some believed that ‘the world’ had become wiser since. At best, one might consider the UN a utopian pilot project, which over time has had less and less chance of success, namely in view of the international political and religious tensions and conflicts that perhaps more than ever characterize the world here in the new millennium.

But just as important for many Danes was that the cinemas could once again play especially American and English films, and such were surprisingly put on the program the very next day, at least in Copenhagen. From June 6, the Aleksandra Theater on Nørregade was able to show the unusually realistic American war film "Airforce" from 1943, in which one of American film's prominent names at the time, John Garfield, had a prominent role. But if the new situation was pleasing to the cinemas and the audience, then it actually came inconveniently for a long cartoon like "Fyrtøjet", because the new situation meant that the film would have sharp competition from especially Disney's long cartoons, regardless of whether it was a new film or a rerun film, which usually used to have a Danish premiere or rerun premiere on Christmas Day 2 at the Metropol Theater on Strøget.

The situation was that "Fyrtøjet" was unfortunately still a long way from being fully finished, so you would be able to program its world premiere. In part, the drawing work, which mainly meant drawing and coloring, and therefore also recording on the trick table, was still far from complete. In addition, the sound work in the form of recording dialogue and music, as well as mixing was not finished. In addition, there were technical delays due to the destruction of the Agfa laboratories in Berlin during the bombing of the city, and it took time to establish a connection with the French laboratory Eclair in Paris, which was responsible for the production of the film copies of "Fyrtøjet", who was to go out and be shown in the Danish cinemas.

A few days after the euphoric and confusing release days, I made the final decision that I would resign my position at Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S, so that I could finish work one week into the month of June. Towards the end of May, I told Børge Hamberg about my decision to stop and try something else. He actually thought it was a bad idea, and he must obviously have passed it on to Johnsen immediately after, because the next morning he came over to the drawing studio, where he, as so often before, stood on the side of my chair and spoke softly to me: "I hear you want to leave us! But why do you not want to think it over once more, because there is a lot of work left to do, also for you. And besides, we would like to move on with new cartoon projects and would therefore be reluctant to do without you! ”

These words I naturally felt honored by, but my decision to stop was irrevocable. The two years of concentrated and intense work behind the light desk day in and day out, and not least the half year of overtime with an approximately 15 hour workday, had made me ripe for a change, almost no matter which one. The mood of upheaval that had spread in the population after the liberation also spread to me, and I therefore felt a great urge to feel 'liberated' myself.

As far as my memory goes, I was the first and so far only one of the staff at Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S who wanted to quit and who therefore quit the job, with effect from one week into the month of June. Noticing without knowing what to do next, apart from trying to finish my own little cartoon "How the elephant got its trunk". But that is another story that one will be able to read about in my biography.

How the work on "Fyrtøjet" continued, I have no personal knowledge of, because after finishing a week in June 1945, I actually lost contact with Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S and the staff for a while. The only one I had close contact with was "Pluto" alias Erik Nielsen, who soon after also resigned his job at the company. But through Karen Egesholm and Mona Ipsen, among others, I have learned that the inking and coloring work continued for a good while into the autumn of 1945. Bodil Dargis has said that there were still some employees in 1946 in the departments in Nørrebro, respectively in the premises at Nørrebrogade / Blågårdsgade and in Stengade. And Mrs. Gerda ”Tesse” Johnsen and Henning Ørnbak have each been able to tell something about what happened next for and with Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S in the next few years. We will hear more about this in the next sections.

Next section: