”FYRTØJET”

Prehistory

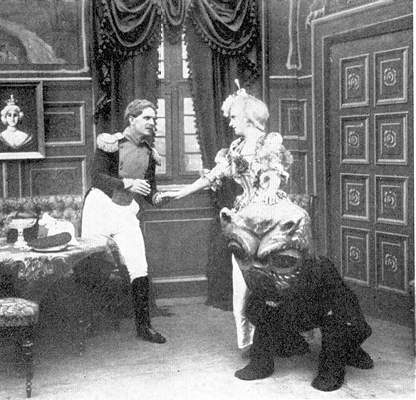

The picture is from a scene in

the long-running cartoon "Fyrtøjet", where the healthy and handsome

soldier marches along the country road, on his way home from military service.

His goal is the big city, where he hopes to find a suitable job. But along the

way, he meets an old witch, who is standing by the roadside in front of his

large, hollow tree - and thus the magical world of adventure begins to open up

to him. The soldier is drawn and animated by Børge Hamberg, and the background

is painted by Finn Rosenberg. - Photo from the film: © 1946 Palladium A/S.

"A soldier came

marching…"

These introductory words to

H.C. Andersen's fairy tale "Fyrtøjet" were to have both good and bad

consequences for the world in several ways, and not least for little Denmark.

The winters of 1939, 1940, 1941 and also the winter of 1942 were the most

severe so far of the century, and during the latter winter the lowest

temperature since 1893 was measured. of scarcity due to the restrictions on

imports that were a consequence of the war situation. Denmark had previously

mainly imported coal from England, but now it was dependent on coal imports

from Germany, where they themselves needed the coal, especially in the war

industry. In addition, the large amounts of snow during the winter caused

serious traffic difficulties, and the capital's milk supply had to take place

in part by means of sleigh transports.

But it was actually the severe winter of

1941/42 that was a major reason why Nazi Germany's attacks and attempts to

conquer Russia were turned into a crippling defeat for the Germans. So in a

sense, the severe winters served a good purpose, although they were hard to get

through for the people, not least in German-occupied Denmark.

Incidentally, the years and

days largely went its calm and accustomed way in little Denmark, occupied as

most were by the small and big joys and sorrows of everyday life. And of course

people enjoyed the sun and heat of the summer months as before. The

entertainment life almost flourished and the cinemas also had reasonably good

conditions in these years and had not yet been hit by such restrictions, which

were soon to be the case. But even shortly before the outbreak of war on

September 3, 1939, noticeable societal restrictions were introduced, including

in the form of export bans for a large number of goods, as well as rationing of

gasoline, gas, water and electricity. In addition, aid workers were called in

to protect the civilian population from the effects of possible airstrikes. A

well-known phenomenon in the big cities was the sandbags that were stacked up

in front of basement windows and many other places, especially by public

buildings, just like public statues, such as. the equestrian statue at

Amalienborg Castle Square, was protected by a stack of sandbags hidden by a

large wooden box.

April 9, 1940 was the day of fate for

Denmark, among others, when German troops outwitted the still sleeping

population early in the morning and invaded and occupied the country, first and

foremost the capital and the larger provincial towns. These places confiscated

the German occupying forces without regard to owners and users the buildings

and other facilities they found necessary. In Copenhagen, the German army

command seized the Hotel d’Angleterre, the Navy Hotel Phønix, and the Waffen-SS

Persil-Kompagniet’s property in Jernbanegade. Part of Dagmarhus was also used,

but the cinema was temporarily allowed to continue showing public performances.

In the ensuing time, the Shell House was seized as the headquarters of the

infamous Geheime Staats Polizei, abbreviated Gestapo. Vægtergården, Vesterport,

Sankt Annæ Palæ is also used for German purposes, and the Palads Teatret was

transformed into the amusement park Deutsches Eck. In 1944, Dagmar Bio was

included in the Armed Forces cinema, which Danes usually did not have access

to. Some of the building's offices were set up for interrogation rooms, where a

number of Danish resistance fighters were subjected to rough interrogation

methods and violent and bloody torture. On the roof of Dagmarhus, the Germans

also had heavy anti-aircraft guns set up, which came into use when English

bombers attacked and bombed the Shell House on March 21, 1945.

But before it had come this far, there had

been fighting in several places between the Danish troops and the occupying

forces at the border crossing in Southern Jutland, and in Copenhagen between

German troops and Danish police, who protected Amalienborg, where the royal

family lived and stayed during the attack. Here, however, the Germans gave up

the fight and withdrew, leaving the place to the Danish police. A few soldiers

on both sides lost their lives, but it soon became clear that the Danish

defense could not provide qualified resistance to the well-organized and strong

German war machine. The supremacy was simply too overwhelming, which the

country's Prime Minister Thorvald Stauning and King Christian X

quickly realized why, allegedly in protest, orders were issued to end all

military resistance. At the same time, a proclamation was made in the form of

posters and readings on the radio, in which the population was urged to

unreservedly observe good peace and order, and otherwise not act outspoken and

provocative towards the occupying power.

Thus began the admittedly forced

co-operation with the Germans, who would later give the government the name of

co-operative government. This co-operation was to last until around the end of

August 1943, when the Germans no longer believed that the Danish government

would be able to prevent the overriding sabotage actions and strikes that

actually bothered the German authorities and interests significantly.

On May 3, 1942, the popular "father

of the country" Thorvald Stauning had passed away, and Minister of Finance

Vilhelm Buhl then took over the leadership of the government until

November 9 of that year. It was a German demand for the government to impose a

state of emergency, with a ban on strikes, curfews, German press censorship,

standard courts, and the introduction of the death penalty for sabotage, which

became the turning point for cooperation with the German authorities. The

demand was rejected by the government on 28 August 1943, which led to the

German Commander-in-Chief in Denmark, General Hermann von Hanneken, on

August 29 proclaiming a state of military emergency throughout Denmark. The

army and navy's crew and officers were interned, but before that they managed

to sink most of the navy's ships, including those that were at anchor or at the

quay in the port of Copenhagen. However, some of the ships escaped to Sweden.

As a countermeasure and to

create fear, the Germans arrested a large number of well-known Danes, some of

whom were probably resistance fighters, while others were quite ordinary

law-abiding citizens. This prompted the government to immediately file its

resignation with the king, after which it ceased to function. The government

was at that time led by the pro-German ex. Foreign Minister Erik Scavenius, as

the Germans on November 9, 1942 had demanded that he replace Vilhelm Buhl. The

latter returned with the Liberation Government on May 5, 1945, of which he

briefly became leader. Scavenius had then become so compromised that he was

finished in Danish politics.

However, the Germans' harsh measures only

increased the Danish resistance and the number of sabotage actions and strikes

increased and culminated in the so-called "People's Strike" in

June-July 1944. Virtually all work was stopped, the factories kept quiet and

the shops closed. And even though the Germans responded again with the

so-called schalburgtage, it did not stop the Danish resistance movement from

continuing the resistance against the Germans, especially not when one

gradually began to glimpse a German defeat on all fronts.

The war, the occupation and

the film industry

However, the year 1943 was to

be the year for Denmark, when the population really began to feel that the war

had moved closer, especially in the form of increased sabotage against

factories and companies that cooperated with the Germans, and in the form of

increased restrictions and lack of basics goods. On January 9, new restrictions

were introduced on electricity consumption in shops and restaurants, and e.g.

shop windows were not to be lit. The ban also affected the S-trains, which were

not allowed to be heated due to a ban on electric heating.

From January 16, the austerity efforts

also had an impact on theaters, cinemas and not least the radio, which in the

winter months all had to end at 22 and in the summer at. 22.30. Restaurants may

not be open longer than until 23, tram ride and the S-trains were to end at. 23.30.

There was still strict rationing of

various daily consumer goods, and in January many butcher shops had to close

temporarily due to shortages of meat. This was mainly due to the fact that the

Germans had "bought up" a large number of pigs and slaughter cattle

and transported them to Germany.

On January 27, an event took

place that shook Copenhageners, but at the same time also gave many new courage

and hope. That day, six English bombers stormed the city, dropping bombs on

Burmeister & Wain's workshops between the harbor and Strandgade. Christians

Church was damaged on this occasion, but even more unfortunate was that the

properties in Knippelsbrogade 2-6 and the sugar factory at Langebrogade were

also hit, and violent fires broke out. Bombs also fell in the neighborhood

around Islands Brygge, so that several thousand people had to be evacuated due

to time bombs and bombs that had not exploded. The bombing claimed 7 lives and

injured many.

On February 2, the extreme frugality with

the use of wrapping paper was imposed. This led to e.g. to that if one got the

bread wrapped at all when one bought it, then it was in the form of a narrow

strip of paper around the middle of the French bread or the rye bread. It was

probably not very hygienic, but experience showed that people quickly got used

to the restrictions, prohibitions and injunctions that were constantly imposed

both before, during and for some time after the occupation. However, the

increasingly serious shortage of raw materials led to the start of a nationwide

cloth collection for the manufacture of new raw materials in March.

As mentioned, the sabotage had already

begun during 1942, and it was further increased in 1943. In an attempt to bring

the sabotage and the saboteurs to life, Captain Lieutenant K.B.Martinsen

(1905-49) formed a military corps on April 1 this year , which consisted of

Danish citizens. The corps was inspired by Himmler's idea of a

joint Germanic SS organization and was originally called the Germanic Corps,

which name, however, was soon changed in favor of the name Schalburg Corps, in

memory of C. F. von Schalburg (1906-42). It was the latter who in the

summer of 1941 established Frikorps Danmark, a military unit of Danish

volunteers under the German Waffen SS. It was Germany's attack on the Soviet

Union that gave rise to the corps' creation, and its purpose was to fight on

the Eastern Front. The corps' first commander was Lieutenant Colonel C.P.Kryssing

(1891-1976), who was later succeeded by i.a. C. F. von Schalburg. The corps was

disbanded in 1943 because at that time it had played its role, and the rest of

the crew was transferred to the SS Panzergrenadier Regiment.

The actual Schalburg Corps was

military, but also housed a civilian unit, called the National Guard. The corps

consisted of a total of 500-600 men, and its main task was to fight the

resistance movement, and the corps members participated extensively in terror,

clearing murders and stabbing.

It was especially the Schalburg Corps'

plainclothes intelligence service, E.T., that was hated by the Danish

population, especially in the big cities. After the dissolution of the

Schalburg Corps in January 1945, E.T. as an independent terrorist group that

carried out a series of so-called Schalburgtager during the rest of the war.

However, the activities of the Schalburg Corps were greatly reduced in the

summer of 1944, when the Freedom Council demanded that the corps be removed

during the people's strike. The majority of the corps' crew was then

transferred to the so-called SS training battalion, which had the barracks in

Ringsted. During the last months of the war, the members of this so-called SS

guard battalion Zealand served as sabotage guards.

The so-called Schalburgtage, the word

formed as an allusion to the word sabotage, set in especially after Hitler's

decree of December 30, 1943, and it was aimed at amusement establishments,

newspaper editors and companies that did not supply war-important goods. In

some cases, they wanted a confusion with the actions of the resistance

movement, i.a. at railway-schalburgtage. The intention was to make sabotage

unpopular with the population, but in reality only the opposite effect was

achieved, as significant sections of the population could relatively easily see

through when it came to sabotage and when about schalburgtage. The illegal

newspapers also helped to inform people about when it was about what.

Even while co-operation policy was at the

forefront, the Danish police did what they could to apprehend, remand in

custody and bring charges against saboteurs and resistance fighters, who were

officially still regarded as harmful to society and criminal elements. On

February 24, 1943, it was officially announced that the city court had handed

down sentences of up to 10 years to 12 people who had helped English

paratroopers. Several of the convicts, along with 12 others, were sentenced to

long prison terms for publishing and distributing the illegal magazine "De

Frie Danske". The term free Danes applied to Danes who, outside the

countries occupied by the Axis powers, made an effort to promote the Allied war

effort. As a single example of a free Dane, mention may be made of J.

Christmas Møller (1894-1948), who had left Denmark illegally on May 14,

1942 and had traveled to London, where he became leader of the Free Danes, and

from where he left the rest. of the war became a fiery speaker in the BBC's Danish-language

broadcasts, which we could hear illegally in Denmark.

The resistance movement's sabotage actions

increased and became more extensive and effective, which led the Riksdag's

co-operation committee until 3 April to make an urgent appeal to the

population, pointing out that the actions were contrary to the king's command

of April 9, 1940, moreover, can have the most serious consequences for the

country and the population.

Speaking of the king, Christian X, on May

15, he again took over the leadership of the government following the illness

resulting from His Majesty's riding accident on October 19, 1942. The king

marked the day by speaking on the radio, recalling his earlier call. to all in

town and on land, to show "a fully correct and dignified conduct,"

implied not to provoke the Germans.

For most smokers, the shortage and

rationing of goods during the war and occupation were a pure plague, especially

when the tobacco factories from the summer of 1943 had to mix the tobacco into

cigars, ceruts and shag Danish tobacco. From the summer of 1944, cigarettes

were also mixed with Danish tobacco, and in the first months of 1945, only

cigarettes made from 100% Danish tobacco were available in the shops. But the

illegal market or "black market", as it was called, which in some

cases was even run from tobacco shops, could still supply foreign tobacco

products and cigarettes, but at sky-high prices, and often against the customer

buying e.g. a pipe in addition. Heavy smokers of cigarettes at that time were

therefore often in possession of a collection of pipes, which was of no use to

them.

One of the more petite moments in 1943 was

the fashion that had at least become widespread in Copenhagen, and it was a

small, crocheted hat or cap in the Royal Air Force colors, i.e. a red ring

surrounded by a white and a blue ring. While I was going to school, I myself

and a few other of my peers wore such a cap on my head almost daily, but where

I had gotten mine from, I do not remember. On July 9, 1943, a ban was imposed

on wearing this skullcap, but it had no practical significance for me, because

I stopped using the skullcap at the end of May this year when I left school and

a short transition became a piccolo in a plumbing company in Frederiksberg.

It was at that time that I myself applied

as a student at Reklamebureauet Sylvester Hvid in Frederiksberggade, and

thereby in reality came a few steps closer to my real goal, namely, to make

cartoons.

On the film front, the war had the

consequence that the Germans immediately after the beginning of the occupation

banned the showing of English feature films in cinemas. These films had

otherwise been popular with many cinema-goers, but could nevertheless not

compete with the American feature films, which were also in large numbers in

the country's cinemas, at least in the big cities. Danish feature films, on the

other hand, were extremely popular in most parts of the country, but the

production could not meet the cinemas' demand and needs.

The German authorities' pressure on the

Danish authorities to increase the import and rental business around German

feature films, which took place via UFA's Danish branch in Nygade 3 in

Copenhagen, did not have much success. The Danish cinema owners made almost all

efforts and twists and turns, to avoid showing German films, among other things

by keeping Danish or American films on the repertoire longer than usual. The

situation was also favorable for Swedish films, and the then fantastically

popular Swedish farce Landevejs-Kroen with Edvard Persson in the lead

role, was held on the poster in Nørreport Bio in Copenhagen from 29 January 29,

1940 to October 7, 1941, i.e. for almost 2 year! This is probably the record

for a feature film in Denmark.

On April 24, 1944, the Germans closed all

cinemas in Greater Copenhagen because some saboteurs, who were called

derogatory by the resistance, had forced the operators in 15 cinemas to show a

slide with a caricature of Hitler and play a gramophone record with anti-Nazi

speech. The cinemas were closed for just over a month and were not reopened

until May 20.

It was in the political and societal

‘climate’ outlined above that the Danes lived their daily lives during the

Occupation, and it was in the same climate that the feature-length film

“Fyrtøjet” was created. Therefore, we must return here to the mention of the

prehistory of the film and the conditions and circumstances that prevailed

around its creation.

Two of the key people in the

production of the feature-length film "Fyrtøjet": On the left the

cartoonist Finn Rosenberg Ammitsted, the inventor of the film, and on

the right director Allan Johnsen, who at the fate or decree became the

film's energetic promoter and producer. - © 1946 Palladium A / S.

The feature film

"Fyrtøjet": Prehistory

As previously mentioned, the

idea to make a long cartoon about H.C. Andersen's fairy tale

"Fyrtøjet", was conceived by the cartoonist Finn Rosenberg Ammitsted.

But whether he may have been aware of and had been inspired by the cartoonist

Richard Møller's plans for a shorter cartoon about the same adventure, is

unknown. However, it cannot be completely ruled out, although I have never

heard Rosenberg mention it. He also did not mention that at first it had been

imagined that the cartoon "Fyrtøjet" would be produced as a short

film. However, the cartoonist, later advertising manager at the pharmaceutical

factory "Ferrosan", Helge Hau, claims that he has heard, but

mag. nature. Henning Pade, who was involved from the beginning of the

cartoon's organization, i.e. from the autumn of 1942, has stated in writing

that he does not think it is probable that Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S

'production of "Fyrtøjet" should originally have been a short film. (Note 1)

In the time after the premiere of

"Fyrtøjet" on May 16, 1946, the film continued to be mentioned in

several newspapers and weeklies, and in it the claim was repeated that it

should originally have been a 10-minute pre-film. This was the case, for

example, in the magazine "BM" (?), Which in an undated issue i.a.

could tell that Allan Johnsen and Co. however, quickly realized that such a

short film would not have opportunities to play its cost home.

After these lines had been

written, the artist and author Lars Jakobsen published the book "Mik

- a biography of the artist Henning Dahl Mikkelsen" on April 20, 2001

", and from this it appears that Jørgen Myller and Dahl Mikkelsen in 1934

made an English language 8-minute cartoon, whose plot is based on Hans

Christian Andersen's fairy tale "Fyrtøjet". But this cartoon, if it

has been made at all, is believed to have been distributed only in England. As

far as is known, it has never been mentioned in Denmark, neither in books, newspapers

nor magazines, except in 1934, when it was mentioned in Drenge Bladet (Boys

Magazine), nor between man and man in the cartoon industry. Only very few

besides Mik and Myller in Denmark have known of the film's existence.

Therefore, it is also unlikely that it may have played any role in Finn

Rosenberg's and Allan Johnsen's choice of the same fairy tale as the basis for

the feature film "Fyrtøjet". (See more about Myller and Mik's

"Fyrtøjet" in the section DANISH CARTOON 1930 - 1942).

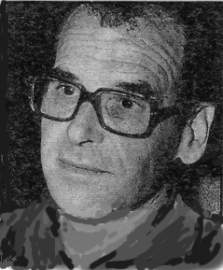

Photo by the artist Richard

Møller approx. 1939-40 at the time, when he was well underway with the

production of his ambitious short, 10-minute cartoon based on H.C. Andersen's

fairy tale "Fyrtøjet”. The then ca. 25-year-old cartoonist, despite his

enthusiasm and diligence, unfortunately did not succeed during this production,

which was primarily due to his lack of experience, especially in the demanding

art of animation. When the later internationally acclaimed animator Børge Ring

several years later had the opportunity to see some of the animated drawings

from Richard Møller's film, he was certainly not impressed. - Photo: © 2007

Knud Møller.

Situation from Richard

Møller's short cartoon version of H.C. Andersen's fairy tale

"Fyrtøjet" (1940). - Image: © 2007 Knud Møller

On the other hand, it can probably not be

completely ruled out that the story of the cartoonist Richard Møller's cartoon

version of "Fyrtøjet" may still have been a joke at the time when the

plans for the feature film of the same title began to emerge. It is a fact at

least that Richard Møller had received his education as a cartoonist from

Jørgen Müller, while he had a cartoon studio in Vesterport in 1932-34. And he

probably got a job again with Myller and Mik, who from April 1939 had become artistic

directors of the Danish, German-owned cartoon company VEPRO.

However, it is documented that Richard

Møller was inspired to make a short film about the fairy tale

"Fyrtøjet", partly by reading the film director Carl Th. Dreyer's

article "Nye veje for dansk Film - og H.C.Andersen" in the

magazine "Avertering" January 2, 1939, and partly by thinking back on

Müller's and Mik’s possibly unrealized project from 1934. Re. Richard Møller

and his career, Børge Ring can tell the following:

"Answers to questions

about Richard Møller (RM):

As a fairly young man, RM was

celluloid markers with Jørgen Müller at the Vesterport studio. When Jørgen went

to England again, RM started a company as a cartoonist. His drawing style was

very similar to Jørgens from the same time ..you know: Columbus, Fyrtøjet and

Carmen. I liked his cartoons… EVERYTHING was interesting then for a boy from

Funen: Disney, Fleischer, Skibstrup, Møller, Myller, Bramming, Engholm.

MIK was probably not "invented"

yet… not with me at least. He first came to Svendborg as a Ferd’nand strip in

Svendborg Avis.

Several years later (1938?), When I was

an apprentice with Jørgen Myller at Gutenberghus, Richard Møller appeared in

B.T. with a still by a cartoon soldier that resembled one of Jørgen's drawings

for Anson Dyer's "Sam, pick up tha 'musket" and the announcement that

NOW H.C. Andersen's fairy tale about the Fyrtøjet was filmed (that you know it)

at Teknisk Film Compagni.

The newspaper received a flush

of letters… among the Protestants were Arne Ungermann and Carl Th. Dreyer and

several Andersen experts. They were all interviewed by phone the next day.

Dreyer called for a renewal in the drawing style. "Why is a cartoon never

made in a warm red chalk tone?"

RM kept a low profile for several years.

Bjørn and I had meanwhile become playmates and daydreamers and one fine day we

were both called out to Teknisk Film Compagni, where RM and the nice director

Hjortø handed us the pencil drawings for a scene of the soldier with a giant

puppet walking on a horizontal pan- background. It was not a cycle [repeat].

There were new drawings for each step, but the soldier became smaller and

smaller without perspective involved (and uglier and uglier and more and more

despairing).

They asked if we would like to take over

the stage, but we apologized. Since then, I have not heard of or from RM. ”

On an autumn holiday in 1936 or 1937, I

saw a lot of cartoons by RM, as Vibe Hastrup's Shoe Cream at an exhibition

about film had set up a cartoon stand, where RM sat at an animation desk and

drew "little men" in Myller-Iwerks-style. In the end, he wrote

"Vibe Hastrup Skocreme" on every magazine. There were four walls

around him full of cartoons in color. A special frieze showed that "it

takes thirty-six drawings to get" Goofy "to take just one step".

”

(Børge Ring in letter of

12.11.01. To Harry Rasmussen).

However, with Børge Ring it must be stated

that Richard Møller's version of "Fyrtøjet" from 1940 allegedly did

not meet the quality expectations, which is why the producer Knud Hjortø

interrupted it to begin with such a promising collaboration. This had thus

taken place sometime before Finn Rosenberg and Allan Johnsen around the summer

of 1942 agreed to try to start the production of a feature-length film project

based on the same fairy tale. However, Richard Møller's plans for a shorter

cartoon version of the fairy tale "Fyrtøjet", with Knud Hjortø,

Teknisk Film Compagni, as the starting producer, were not intended for cinema

use, as it was shot on 16mm film for use in the private home cinema. However,

Richard Møller had already aired his plans to make a short cartoon about

"Fyrtøjet" for B.T. January 3, 1939, reportedly inspired by film

director Carl Th. Dreyer's article in the January issue of the monthly magazine

"Avertering", which had been published the day before. The next day,

January 4, Politiken brought an interview with Richard Møller, who on that

occasion had made a quick drawing for the article. It did not appeal to

intellectual and artistic readers, and at the time it caused a number of

readers to protest strongly against Richard Møller's plans. Among the

protesters were well-known as well as unknown names, as well as several

literary H.C. Andersen experts. (Note 2)

As mentioned, it can be stated

that Richard Møller's cartoon project was at least partly inspired by Carl Th.

Dreyer's article, which as mentioned was read in the magazine

"Avertering" for January 2, 1939. This article may probably also have

inspired Finn Rosenberg, who as an advertising cartoonist must undoubtedly have

read the mentioned magazine. In the article entitled New Roads for Danish Film

- and H.C. Andersen, Dreyer states, among other things:

"There is agreement that Denmark is

closer to shooting an H.C.Andersen film than any other country. There is also

agreement that such an effort must be made in money and work that the film

becomes a worthy expression of our great , national poet and acts as propaganda

for Danish culture and art.

It is a high and justified goal to set,

and it is to be hoped that those who have the courage to put up with this great

task are also aware of both the difficulties and the responsibilities. "

Dreyer then discusses whether the film

should be a biographical depiction of H.C. Andersen's life, and after reviewing

the various possibilities for such a film, he continues:

"How it goes now or not, the

biographical H.C.Andersen film, then there is another H.C.Andersen film that

the world is waiting for and longing for, an H.C.Andersen film, which sooner or

later will be made, and which we should get started with the sooner the better,

all the more so as its economic opportunities are far more favorable than for

the biographical film.

The idea has been put forward that no

better characterization of the poet's personality can be given than by

retelling in pictures one or some of his adventures. This is of course true,

but not if one imagines the adventures filmed, played and photographed like a

regular movie. The photographic lens is excellent at reproducing the tangible

reality, but is only a poor help when it comes to producing an illusion of the

unreal, and in the face of the fairy-tale spider web of fairy tales, it will

quite fail. In order to recreate on the screen the enchanting grace of the

fairy tales, the film must resort to other means. The real H.C. Andersen

adventure film must be made by a Danish painter.

When the first cartoon

appeared many years ago, the more foresighted could predict that one day a

"painted" film would emerge as opposed to the "played"

film, a "living painting" similar to the "living drawing".

The doubters of that time will hardly doubt any more, and if they do, they

should go in and watch the Snow White movie. "(Note 3)

In his article, Dreyer then touches on the

preliminary history of the cartoon genre and mentions names such as Oskar

Fishinger, Willem Bon and Lotte Reiniger, after which he discusses what he

calls "the entertaining cartoon". As a tentative highlight in this

category at the time, Dreyer again mentions the Snow White film, which he does

not consider a significant work of art. He justifies this in the following way:

"Measured by the acre of art, it is

not a significant work, and its many pleasing and endearing qualities can be

unspoken - pointing out imperfections, especially the somewhat glamorous psychology

of the protagonists as well as the often scratchy and grinding, often flat and

fresh color effects. Walt Disney is an entertaining and inventive cartoonist

and well into the craft of cartooning, but he is certainly not a great artist.

"

It is Dreyer's view that, in terms of

stylistic as well as literary content, the cartoon does not have to

"trample on the heels of the somewhat childish comics of the

magazines," but both can and should rise to a truly artistic level. He

believes that it will be possible to do this in Denmark, where there are a

number of significant drawing and painting artists, and this, together with the

fact that with H.C.Andersen’s adventures we own one of the largest literary

assets in the world, could end up with a good result.

In Dreyer's opinion, cartoons

of especially H.C. Andersen's lyrical fairy tales would be of artistic quality

if they were made on the basis of drawings or illustrations of e.g. Vilhelm

Pedersen, Axel Nygaard, Mogens Ziegler, Arne Ungermann, Hans Bendix or Jensenius.

As examples of humorous adventures, Dreyer mentions Little Claus and Big

Claus and the Fyrtøjet, which he assumes that especially artists

like Arne Ungermann, Hans Bendix and Jensenius would be

self-described to design. And for the dramatic fairy tales, he believes that

painters like Niels Larsen Stevns, Hans Scherfig or Fritz Syberg

would be suitable. Dreyer also highlights Larsen Stevns as the obvious

"designer" of a biographical H.C. Andersen film, which he justifies

with the collection of colored illustrations (watercolors), which he had

painted for a then intended image version of "My Life's

Adventure". The watercolors were exhibited at Den Frie in the autumn

of 1938 (?). The picture edition with Larsen Stevns' illustrations was

published in 1943. (Note

4)

In 1914, Dania Biofilm Kompagni shot a

"feature film" about the fairy tale "Little Claus and Big

Claus". The screenplay for this was designed by the author and then

director of Gyldendals Forlag, Peter Nansen (1861-1918), who also sat on

the board of Dania Biofilm Kompagni. He was for a time married to the

famous actress Betty Nansen, b. Müller (1873-1943), who from 1917 until

her death was director of the Betty Nansen Theater in Frederiksberg. As

director of "Little Claus and Big Claus", he chose the actor and

author Elith Reumert (1855-1934), who was considered to have a good

knowledge of H.C. Andersen and his writing. As a boy he had met the great poet

alive, just as he had a personal acquaintance with some of the persons who had

known H.C. Andersen closely. However, it was not until 10-11 years later that

he wrote a few books about the man H.C. Andersen in particular. The first, H.C.

Andersen and Det Melchiorske Hjem, was published in 1924, and the second, H.C.

Andersen as he was, was published in 1925, both at H. Hagerups Forlag,

Copenhagen. (Note 5)

The one main role as Store

Claus was played by the then actor Benjamin Christensen (1879-1959), who

later distinguished himself as one of Danish silent film's artistically best

directors. After many years as a film director in Germany and then in

Hollywood, he returned to Denmark in 1939 and directed the feature film "Divorce

children", for which he had also written the screenplay. In the years

1940-42, he was responsible for four more significant Danish feature films. In

1944 he received a grant for Rio Bio at Roskildevej 301 in Copenhagen.

The second lead role as Little Claus was played by the actor Henrik

Malberg (1873-1958), who had made his film debut in 1910 in Regia

Kunstfilms Co.'s film adaptation of Oscar Wilde's short story "Dorian

Grays Portrait", and who as late as 1955 got a lead role in Carl Th.

Dreyer's film adaptation of Kaj Munk's play "The Word". Robert

Storm Petersen had a minor role as a farmer in "Little Claus and Big

Claus". In a still photo from the film, he is seen with Benjamin

Christensen next to a horse-drawn carriage, on whose belly sits a man in a hat

and behind him a figure bends forward. The latter two persons have not been

identified. The image is one of the few still photos preserved from the film. (Note 6)

Under the title Store Klaus og Lille

Klaus, the fairy tale "Lille Claus og Store Claus" was made in 1930

as a puppet film by the photographer Christian Maagaard Christensen at

the then newly established Nordisk Tonefilm, which, however, had nothing to do

with Nordisk Films Kompagni. The film was dubbed by "Lange Lyd" alias

tone- or sound master Henning O. Petersen (1894-1988), who 1928-46 was

tonemaster at Nordisk Film in Valby and then workshop manager at Nordisk Films

Teknik in Frihavnen. The film, which is about 600 m = approx. 22 minutes, was

shown in Kinografen 24.8.-8.9.1930. (Note 7)

However, hardly everyone was or will agree

with Dreyer's assessment of the Snow White film as well as of Walt Disney, but

his view was largely shared by the fine cultural establishment, both then and

later. The question is, however, whether the assessment can be characterized as

factual, as one must ask oneself what prerequisites the otherwise

well-respected and world-famous feature film director Carl Th. Dreyer had to be

able to assess the cartoon medium and its special history, terms and

possibilities.

Dreyer, who at the time

apparently had great and optimistic confidence in Danish film producers, also

expresses the opinion that the task of producing a Danish H.C. Andersen fairy

tale cartoon must be stumbling close to a Danish film producer, and he

continues:

"[...] Whether the interested producer

would then try to realize the film in this country by summoning foreign

technicians (if we do not already have them good enough, which I am inclined to

believe) - or would prefer to ally with an English or American partner is in

the first place a subordinate question. The important thing is that there is a

need for the "drawn" or "painted" H.C.Andersen adventure

film, and that Danish film should not wait until this rich, national treasure

is taken out of the hands of us, but without delay step to the work. The risk

is small, because you know in advance exactly what you are getting along with and

can follow the realization step by step. movies without major difficulty can be

dubbed in other languages. " (Note 8)

Speaking of cartoons based on one of H.C.

Andersen's adventures, Storm P.'s photographer Karl Wieghorst had already in

1928 and 1930 tried to film some of Andersen's adventures (See note 7). And in

1931, Walt Disney was able to present his cartoon short version of The Ugly

Duckling ("Den grimme Ælling"). It was redrawn several years

later in a new and modernized version, which premiered in 1939 and won an Oscar

for best short cartoon that year. In both cases, however, there was an even

very free reproduction of the action in Andersen's fairy tales, and the moral

or aim of the fairy tale was trivialized beyond recognition. However, this does

not prevent the latter version from being a very beautiful, touching and

technically good cartoon, which both children and adults have been able to

enjoy both then and at the later screenings in cinemas around the world, and

yet later in television and in video editions of the film.

Above are the two most

prominent figures in the Danish cartoon industry in the 1930s-40s. To the left

Henning Dahl Mikkelsen (Mik) and to the right the undisputed nestor of Danish

cartoons, Jørgen Müller (Myller), both photographed around Christmas time 1941.

In 1942-43 both were in question as directing animators on the feature film

"Fyrtøjet". - Photos: Excerpt from a group photo taken at VEPRO's

Christmas party in 1941. - Dansk Billed Central.

When Dreyer thought or assumed that we in

Denmark had people who would technically be able to make such a film, he

probably thought of Jørgen Müller and Henning Dahl Mikkelsen and their

employees, who at the end of 1938 until the spring 1939 worked for Gutenberghus

Reklame Film. In the article, however, Dreyer does not content himself with

presenting airy ideas, but throws himself into a budgetary calculation of what

a so-called all-night cartoon would cost to produce in 1939 awards. He assumes

that "a technically impeccable cartoon in color and with tone is at home

at about 60 kroner per meter. Let us be large and count twice as much for the

adventure film. We will then see that an all-night cartoon of 2000 -2400 meters

will cost less to produce than just the Danish version of the played

H.C.Andersen biography, but while the cartoon can easily be

"translated" into other languages and thus can be shown

all over the world, the Danish version of the feature film can only be

performed at home." (Note

9)

If you count on Dreyer's

indication of the price for a Danish cartoon of 2000-2400 meters, which means a

playing time of 72-86 minutes, we come up with a price of DKK 120 per. meters

to a budget of 240,000-288,000 DKK, well noticeable in 1939 prices. In

comparison, it cost around DKK 1,000,000 to produce the 76-minute-long

"Fyrtøjet" in the years 1942-45, i.e. approx. five to six times as

much as the price estimated by Dreyer! For further comparison, it cost 1.7

mill. dollars in 1937 prices to produce the 80-minute-long Snow White film,

which also took about 3 years to produce, but with a staff of 900-1000 people.

The comparison lags, however, as the work procedure at the Disney studios was

organized and rehearsed through years of experimentation and practical

experience, gained during the production of a large number of short cartoons,

both in the Mickey Mouse series, the Donald Duck series and others, but perhaps

especially in the generally more 'serious' Silly Symphony series.

Danish cartoon production had been

discontinuous until 1939, and the few leading cartoonists who were at that time

actually consisted of only two people, namely the aforementioned Jørgen Müller

and Dahl Mikkelsen, who had both learned the profession in England. However, a

slightly younger generation of Danish cartoonists was gradually on their way

with names like Bjørn Frank Jensen, Børge Hamberg, Erik Rus, Kjeld Simonsen and

Erik Christensen. They had all at the time when "Fyrtøjet" was put

into production, been employed by the cartoon company VEPRO.

But producing a cartoon without a

storyboard was unthinkable at Disney, on the contrary, it was such an obvious

and indispensable part of the production process. In addition, his staff,

including especially instructors and animators, for the reasons listed above

were significantly more well-trained and experienced than was the case with the

animators who worked on "Fyrtøjet". And when it comes to finances and

budgets, Danish cartoon production does not stand comparison with American

cartoon production, which operates with budgets of millions of dollars when it

comes to feature films, where in Denmark you only have to calculate a maximum

of millions of kroner. A direct comparison between the terms and conditions of

Disney's cartoons and the terms and conditions of production of

"Fyrtøjet" is therefore neither possible nor reasonable. One should,

however, apologize to Dreyer for being well-meaning, but objectively

inexperienced and ignorant in cartoon production.

But very much speaking of

Dreyer's above-mentioned and partly quoted article, this was of course read

with particular interest by the cultural and film journalists of the rest of

the press. At least it gave the morning paper "B.T." on the occasion

of an interview with the undisputed first man of Danish cartoons, Jørgen

Müller, who read in the newspaper for Saturday, January 7, 1939. Under the

headline H.C.Andersen-Filmen: A Danish Cartoon is possible, Jørgen Müller is

asked what possibilities there are will be in Denmark to make an all-night

cartoon based on one or possibly more of H.C.Andersen’s adventures. Müller

optimistically estimates that 12-14 people would be able to produce such a film

in the course of a year, and that it would cost approx. DKK 250,000 to produce.

(In comparison, it took about 200 people around 3 years to produce the

"Lighthouse", which, as previously mentioned, came to exceed the

original budget by an amount that was about six times higher than anticipated

and planned). (Note 10)

In the article, Jørgen Müller, as a

professional, speaks objectively about which expense items one can count on. He

states that approx. 7000 meters of raw film, 3000 meters of raw film for sound

and a cut copy of both strips, a total of approx. 4500 meters. In addition,

there are 10 copies of the finished film, which would all cost around DKK

70,000. To this must be added fees for screenwriter (s), composer, musicians

and actors, who for the latter must record the lines of the cartoon characters.

Next came salaries for the artists, which

Müller estimated to include 12-14 people, namely an artistic designer and three

key artists, and some middle artists, as well as three women with the felt-tip

pen to "trace" the pencil drawings on celluloid boards, and three or

four young ladies to color these. Müller further estimates that the total

number of celluloid sheets will cost approx. DKK 7-8,000 (Note 11)

Neither Jørgen Müller nor the journalist

who signs Maurice directly mentions anything about the fact that the intended

feature film could possibly be about a cartoon film adaptation of the fairy

tale "Fyrtøjet", but the possibility appears indirectly from the

article's introduction, which states the following:

"Carl Th. Dreyer's

proposal to create a Danish H.C.Andersen adventure cartoon is now being eagerly

discussed among cartoonists and filmmakers. One of the most important problems

is this: Is it technically possible to produce such a film at home? To get this

question answered, BT has approached Jørgen Müller, who for half a dozen years

has been involved in the production of advertising cartoons both here and in

England, where he originally learned the technique. the other day announced his

private H.C.Andersen-Film, saying: etc. etc."

Apart from the fact that Richard Müller

was named Møller by last name, he had, as previously mentioned, plans to make a

short cartoon about the fairy tale "Fyrtøjet", intended for a then

growing market for 16mm film. The project had shortly before been mentioned in

the press, just as it was later mentioned again in the Copenhagen newspaper

B.T. According to the mentioned newspaper, Møller had entered into an agreement

with Teknisk Film Compagni for the production of an approximately 5-6 minute

long cartoon, based on H.C. Andersen's fairy tale "Fyrtøjet". It was

director Knud Hjortø, the founder of Teknisk Film Compagni, who was the

initiator of the film, and the company's co-founder, the film photographer

Fritz Jensen, who was to photograph the film. However, Richard Møller's "Fyrtøjet"

was discarded by the manufacturer, allegedly because it did not live up to

expectations in terms of quality.

However, Knud Hjortø did not give up the

idea of producing entertainment cartoons for the 16mm home

cinema. The same company therefore produced the following year, in 1940, the

cartoon Peter Pep and Shoemaker Lace Boot, which the cartoonist Erik Rus

(Christensen) (1920-87) was partly the author of, and which he was partly also

the main animator, with Børge Hamberg (1920-70 ) as an assistant and in-betweener.

Fritz Jensen is credited as a photographer on this cartoon. The following year,

the same company and team produced a two titled Peter Pep's Attempt. (Note 12)

Above is Nordisk Film's

version of the fairy tale "Fyrtøjet". The film was produced in 1907

and had a running time of 8 minutes, which was the normal length for

"feature films" at the time. To the left is the director Viggo Larsen

in the role of the soldier, and to the right Oda Alstrup in the role of the

princess. The dog, which in this case has brought the princess from the castle

to the soldier's accommodation, is clearly a black-clad man with a cardboard

making head. - Photo: © 1907 Nordisk Films Kompagni A / S. The photo is

reproduced from Arnold Hending: The film and H.C. Andersen. Kandrup and Wünsch.

Copenhagen 1935.

However, it was far from a new idea to

make a cartoon about H.C. Andersen's fairy tales at all, nor specifically about

the fairy tale "The Lighthouse". In the book Filmen og H.C.Andersen,

the author Arnold Hending says, among other things, that Nordisk Films

Kompagni's first film director, Viggo Larsen, in the year 1907 directed a total

of three H.C.Andersen adventure films, namely "Lykkens Kalosker",

"Fyrtøjet" and "Ole Lukøje", each of 8 minutes of playing

time, which was considered a considerable length for films at the time. But

neither director Ole Olsen, photographer Axel Graatkjær or Viggo Larsen himself

were particularly satisfied with the result when the films were finished. After

first mentioning "The World's First H.C.Andersen-Film!", "Galoshes

of Fortune", 1907, which took two working days to record, and which

did not arouse the expressed joy or enthusiasm of those involved, Arnold

Hending continues to tell specifically about "Fyrtøjet":

"And also not very reverently, they

started with "Fyrtøjet", in affordable surroundings, conjured up by

the painter Robert Krause and donated free of charge on Roskilde Landevej by

Vorherre.

With a minimum of confidence that

"Fyrtøjet" should pay off, Nordisk made a new scratch for the taste.

They took some pictures on the wooden floor and then went, provided with a

hollow tree, to the country road where, curiously enough, the great H.C.

Andersen acquaintance Jean Hersholt had made his debut in front of the camera

for 7 kroner the year before.

The director and first actor Viggo Larsen

says about this recording: When I (it must be in consultation with Ole Olsen)

chose "Fyrtøjet" it was not because Andersen was so famous abroad -

it was not known at all at home. The Danes have always taken a long time to

discover that a countryman was known abroad. No, the cheerful, naive Aladdin

theme appealed to me. But there it was with the dog! Where do I get a

dog with eyes as big as the Round Tower, or just as teacups? My director managed

this point using three sets of black tricot and three mighty cardboard dog

heads. We were at this point bloody amateurs, yes in decorative terms almost

illiterate, but we possessed the courage bred by youth and naivety. We worked

after the release: It must go fast, it must not cost anything, and the film

must not be over 165 meters long. One imagines the whole adventure game in 8

minutes. One cannot even read it from the magazine at that time.

It was difficult to find a

piece of road untouched by civilization, Larsen continues, but he succeeded.

Petrine Sonne played the witch and I myself the soldier. Of the other players,

I remember today only belly talker Lund as the king, the adorable Oda Alstrup

as the princess and Storm P. as one of the servants in the "room",

where the soldier has fun wasting money on unknown people. - Of course, there

had been occasion to show lively street scenes in old costumes between old

houses, but such luxury footage would only prolong and make the film more expensive.

The final scene was taken in Søndermarken, where we had built a throne next to

the tree, where the master had thrown the rope, which was to be placed around

my neck, around a thick branch. It was of course only an extract of the fairy

tale we got made - and why I deliver this memory from 1907 and smile sadly when

I think back ... yes, it is due to the memory of the moments when Oda Alstrup

twice lovingly wrapped her lovely arms around my throat!

But I also remember that Viggo Larsen's

lack of hope for a successful outcome of an adventure film was this, that it

was his opinion (long before cartoons were created) that only in cartoons could

the right result be achieved. The camera was him, and here he probably looked

right, too realistic! "(Note

13)

Above is another scene from

Nordisk Film's version of the fairy tale "Fyrtøjet". On the left,

Gustav Lund is seen in the role of the king, then Oda Alstrup as the princess

and in the middle Clara Nebelong in the role of the queen, while the director

Viggo Larsen is seen in the role of the soldier held back by a pair of lackeys.

- Photo: © 1907 Nordisk Films Kompagni A/S. The photo is reproduced from Arnold

Hending: The film and H.C. Andersen. Kandrup and Wünsch. Copenhagen 1935.

The lyricist and author Arnold Hending,

who had specialized in the history of Danish film since the mid-1930s, also

mentions the feature film "Fyrtøjet" in the book "Filmen og

H.C.Andersen", about which he writes the following:

With improbable courage and willingness to

sacrifice, however, the cartoon "Fyrtøjet" was led to a Danish,

European and American premiere. competition, had almost the sound of fanfare.

That it took a small army of employees

just three years to produce the fairy tale, one hints at the Sisyphus battle.

It had started with a few cartoonists, under the production manager Allan

Johnsen's chambriere, but gradually the staff of cartoonists developed to 200,

and it was learned that these had a total of one and a half million drawings

made under the supervision by Svend Methling. The film became the most

expensive yet produced in Ole Olsen's homeland.

A few figures will be a surprising

projector on the scope of the work: Produced pencil drawings: 543,000 - Drawn

on celluloid: 433,500 - Colored drawings: 433,500.

There were six main

characters. Børge Hamberg created the healthy soldier, whom Poul Reichhardt

voiced, Preben Dorst drew the princess, and Bjørn Frank Jensen struggled with

the work with the humorous characters, but all the efforts did not lead to the

great success. After the premiere in Palladium, it was said: "When you

have chosen to build the film over H.C.Andersen’s adventures, it is probably

because you wanted to create something that was not only known around the

world, but was also specifically Danish. That Andersen's genius did not and can

not be translated into film and therefore only the action that remains is a

matter in itself, but characteristic of the whole enterprise is that one looks

in vain for the Danish in the film. All landscapes and cityscapes - even if

they reproduce the Round Tower - is so obviously made with an alas, far too

squinting eye for the fantasy - or pancake world we know from the Technicolor

movies from across the Atlantic. In other words, the result was as expected -

that is, not so good."

There was, however, a remark that the film

offered glimpses of reconciling moments, such as a funny physiognomy or a

musical passage that rose above the instantaneous forgotten - and then the film

was free of flatness - it was called reconciling.

The audience liked the film and perhaps not

least the music composed for the occasion by Vilfred Kjær and Eric

Christiansen, but when "Dansk Farve og Tegnefilm A/S" next time

dreamed conquering dreams in color, all stars went out.

It was stated in the magazines, in the

spring of 1949, that, after the so successfully completed task with

"Fyrtøjet", it had now been decided to produce an all-night film

about "Klods-Hans", and that the company from the Ministry of

Education had been notified that the state would support the enterprise. It was

no wonder that, after that solar bulletin, one got started. Svend Johansen made

the drawings for the background sketches, and Hans Schreiber was ready to

interview his muse, the screenplay was by Johnsen and Henning Ørnbak, and

negotiations with the actors who were to cast voices for the event had begun.

And while the sore-nosed baby

"Fyrtøjet" is still being built in London, disaster strikes. Allan

Johnsen, who is ostentatiously shy of statements of a solid nature, simply

tells the press that he obviously does not want to hide that he is disappointed

- but, he adds - now he no longer wants cartoons to order. A collaboration that

had begun in the spring of the happiest hopes has broken down. Farewell then to

new advances on domestic soil in Technicolor.

With "Klods-Hans" a Danish effort

with many possibilities collaborated. [...] "!! Arnold Hending: Filmen og

H.C.Andersen, p.30-32. - The quote from one of the reviews of

"Fyrtøjet" is from May 17, 1946 and was under the heading "Den

danske Tegnefilm, der kostede en Million” to read in Berlingske Tidende.

Arnold Hending's brief description of the

creation of the feature film "Fyrtøjet" and its reception in the

press is largely in line with the facts and events. It was as previously

mentioned mag.art. Peter Toubro, who - with literary assistance of mag.art.

Henning Pade - wrote the screenplay for "Fyrtøjet". But it is not

correct when Hending writes that the screenplay for the feature film

"Klods-Hans" was written by Allan Johnsen and Henning Ørnbak. It was

instead written by the playwright Finn Methling and with mag.art. Henning Pade

as a literary consultant. We must return to this cartoon and its ill fate in a

chronological context.

The knowledge of the feature film

"Fyrtøjet"'s prehistory, which is the basis for this portrayal, is

partly due to what I, Harry Rasmussen, have been told personally by especially

Finn Rosenberg, and partly by other parties involved, including not least by

Henning Pade, who was also involved from the very beginning, but who was

arrested by the Gestapo on September 3, 1944, on suspicion of participating in

the resistance struggle. He was remanded in custody until the day of

liberation, May 4, 1945. Finally, additional information about the film's

prehistory and origins is taken from several places, including with some still

living people who were employees of "Fyrtøjet".

In Niels Jørgen Dinnesen and

Edvin Kau's "Filmen i Danmark", Akademisk Forlag 1983,

"Fyrtøjet" is mentioned in connection with the mention of Dansk

Farve- og Tegnefilm A/S 'next feature film production "Klods-Hans".

The mention is accompanied by a single image from "Fyrtøjet", which

comes from the front page of the film program for which Bjørn Frank Jensen has

specially made drawings.

The cartoon "Fyrtøjet" is also

mentioned in a caption in Erik Nørgaard: Live pictures in Denmark, page

179, where under a close-up of the witch it says the following:

"The Witch in the first Danish

animated feature film," Fyrtøjet "from 1946, staged and organized by

Svend Methling. It was a more daring than successful experiment."

But according to what Finn Rosenberg has

personally told me while we were still working on "Fyrtøjet", it was

he who got the idea and took the initiative for the film. Which partly also

appeared from the press coverage of the film, and partly later also has been

confirmed in writing by Henning Pade. How Finn Rosenberg had come up with

exactly that idea, he did not mention anything himself, but the idea of an

H.C. Andersen fairy tale cartoon was, so to speak, in the "air" at

the time, and especially after Carl Th. Dreyer with his article in

"Avertering" had nurtured the idea, and after the expert Jørgen

Müller had commented on the practical possibilities that one in Denmark would

be able to implement such a project. For Finn Rosenberg, it happened in

practice in such a way that when he was employed as an advertising designer at

the advertising agency Monterossi around 1942, he was one day given the task of

illustrating the book "Fra Dyreskind til Celleuld", which was

written by manufacturer and wholesaler Allan Johnsen . On the back of the book

was the following text:

"Here is a book for the

inquisitive reader, not only the young man who seeks information about the day

and the practical questions of the road, but anyone can in this interesting

depiction find something new and expand their knowledge. It is the first time a

Danish author on a popular Maade has described the history of the spinning

fabrics, and it has been made so amusing and easy to read that the book will

find its way to the largest audience." (Note 14)

The book, which according to Henning Pade

was written during the summer of 1942, tells about the raw materials that have

been used throughout the ages to spin textiles with linen, wool, silk,

artificial silk, cell wool and milk wool. The depiction of the various

substances is richly illustrated with cheerful drawings and enlightening,

schematic drawings of the processes behind the technical production of the

substances' creation. Cell wool, commonly referred to simply as "cell

wool", which in the latter part of the war came to play a major role in

the textile industry, was made with spruce cellulose as a raw material, and

after a mechanical and chemical process, the wood mass was transformed into

fine threads, which one could spin and weave textile fabric off.

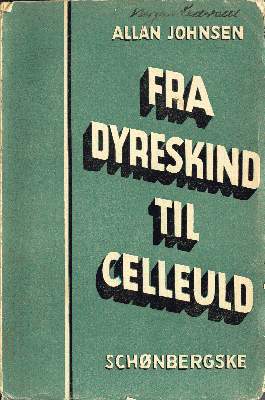

Above is the front page and

table of contents for Allan Johnsen's book "Fra Dyreskind til

Celleuld", Schønbergske Forlag 1942. The book's illustrator was

advertising designer Finn Rosenberg Ammitsted, who at the time was employed by

the advertising agency Monterossi. - Drawings © 1942 Allan Johnsen and

Schønbergske Forlag.

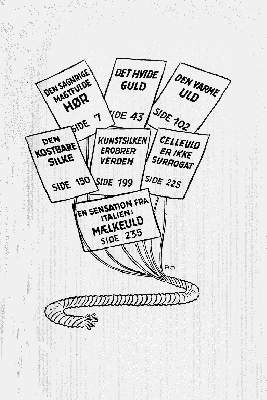

Two examples of Finn

Rosenberg's illustrations, resp. pages 70 and 75, for Allan Johnsen's book

"Fra Dyreskind til Celleuld". As can be seen, the drawings emphasize

the slightly comical and humorous. - Drawings © 1942 Allan Johnsen and

Schønbergske Forlag.

The new product was originally developed

and manufactured at two factories in Germany: Cologne-Rottweil A.G. and Dynamit

AG, and the new product was called "Vistra", a name composed of the

two companies' telegram addresses "Sivispacem", an abbreviation of

"Si vis pacem para bellum" ("If you want to win the peace, then

prepare war"), and "Astra", which means "star". Page

231 Johnsen states, among other things:

"[...] As early as 1922, the garment

factories in Germany began to take an interest in the Celleulden, which also

found its way to several of Europe's countries. Germany created the Celleulden,

and it made rapid progress. the cell wool that was to liberate Germany from

England and America's monopoly. The stranglehold of the English blockade was no

longer to hit Germany's industry. Germany had enough wood, especially after

Austria had come under German territory." (Note 15)

It was allegedly during the collaboration

on the book that Finn Rosenberg presented to Allan Johnsen the idea that one

should make a preferably longer cartoon about H.C. Andersen's fairy tale

"Fyrtøjet". And Johnsen, who as a result of the war and the

occupation at that time, otherwise, like other textile manufacturers, had

problems obtaining textile fabrics for his manufacturing and wholesale

business, was immediately involved in the idea. He, who lived in Gentofte and was

an avid sports rower, had in 1938 been a co-founder of Skovshoved Roklub,

and among its members was spoken mag.art. Peter Toubro and mag.art. Henning

Pade. Johnsen now got these two literary-savvy men interested in the film

project, and together with Finn Rosenberg they wrote the screenplay for the

film in the summer of 1942. According to Henning Pade, however, it was Toubro

who was primarily responsible for preparing the screenplay.

Also according to Henning

Pade, it started around the same time, i.e. the late summer of 1942, some

"consultations" and negotiations, including with director Holger

Brøndum (1899-1970), Nordisk Films Kompagni. The negotiations were about

financing and company formation, but Brøndum was a trained and tough

negotiator, who naturally looked at his own company's interests in the context.

In addition, Brøndum was a member of the board of the cartoon company VEPRO,

and as such he naturally knew who the artistic directors of this company were.

Furthermore, it was he who in 1939 had the cartoonist Kjeld Simonsen placed as

an animator student with Jørgen Müller and Dahl Mikkelsen at VEPRO. But Brøndum

has obviously not had confidence that Allan Johnsen and Co. would be able to

cope with the daring task of producing a long cartoon á la "Snow

White" or "Gulliver" film, so therefore it has probably been his

opinion that VEPRO would be a significantly more responsible producer of such a

cartoon. It can probably therefore be considered to have been Brøndum who made

sure that the relatively more experienced cartoonists Müller and Mik were

involved in the negotiations. But Allan Johnsen, for his part, was at least as

interested in the project not slipping out of his own hands, and it therefore

ended up that he interrupted the negotiations with Nordisk Film and instead

decided to form an independent company. On December 5, 1942, "Dansk Farve-

og Tegnefilm A/S" was founded, with the production of "Fyrtøjet"

as its immediate purpose. If all went well, other similar projects would later

be put into production.

Above is the letterhead that

Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm A / S used from 1942 and at least up to and including

1952. The company's office address was Frederiksberggade 10, 3rd floor, the

telegram address "ALLANJO" and the telephone number Central 16432. -

The letterhead is scanned from a reply letter, dated November 1, 1952, which

Harry Rasmussen received the next day.

As far as is known, it was first and

foremost Allan Johnsen himself who raised money in the limited company, but he

also got several other textile manufacturers and textile wholesalers interested

in joining.

But since cartoon production on a larger

scale was a hitherto untested area in Denmark, at least in terms of

entertainment cartoons that lasted longer than 8-10 minutes, the prospects of

getting the invested money back home were very uncertain. The fact that trade

with foreign countries, with the exception of Nazi Germany, had largely ceased

at that time, has probably played a large part in this, as it led, among other

things, to a form of wealth, especially among wealthy people. In addition,

investors dared to invest their money in such a special film production as a

Danish feature film was at the time, because the German occupying power had

from the very beginning banned cinemas from showing English films, and after

America joined the war in 1941 also made big obstacles to the showing of

American films.

This meant, among other

things, that Walt Disney's long cartoons, both the new and the slightly older

ones, could not or had not been shown in Danish cinemas. On the other hand, the

Germans so far allowed American short cartoons to be shown in cinemas. This

meant that the hugely popular Metropol's Christmas Show could still be shown on

the program at Christmas time, just as short Disney cartoons - and by the way also

Max Fleischer's short cartoons - still had to be shown as pre-movies, as long

as the relatively few remake films were still allowed. However, it was only the

American cartoons that had come to this country before the German occupation of

Denmark on April 9, 1940, that had to - and could - be shown. Therefore, in the

years 1940-44, Metropol's Christmas Show consisted only of cartoons that were

from 1939 and backwards. (Note

16)

But even though Dansk Farve- og Tegnefilm's

shareholders and management could not know how long the German occupation of

Denmark would last, or whether Germany would eventually win the war, which only

a few hoped for, it was expected to be able to finish the film so timely that

it would in any case be able to avoid any competition from the sovereign

American cartoons. European cartoon production was extremely minimal at the

time, but it did exist, not least in France. This also applied to the German

cartoon production, of which in 1944 a couple of short cartoons were shown in

D.S.B.-Kino, which was housed at Copenhagen Central Station, where the

highlight was usually the Popeye (Skipper Skræk) films. But when the planning

of the "Fyrtøjet" film began in 1942, only a few people believed that

the war would soon be over, in favor of the Allies, so they continued

comfortably with the very ambitious cartoon project.

There is no exact and verified

information on how Nordisk Film and Holger Brøndum, and thus VEPRO and Jørgen

Müller and Henning Dahl Mikkelsen, came into the picture in connection with the

cartoon "Fyrtøjet". But according to Henning Pade, it was Allan

Johnsen who approached Brøndum in the hope of having Nordisk Film as a

co-producer of "Fyrtøjet".

As far as is known, it is not documented

that any negotiations have taken place with VEPRO's management at this time,

but as mentioned above, it is highly probable that this has happened. In a

newspaper interview in B.T. for January 7, 1939, Jørgen Müller - he was

probably still employed by Gutenberghus Reklame Film - had indirectly stated

that he believed that a staff of about 17 employees could undertake to carry

out such a large-scale project as a feature film, and it was precisely a staff

of well and good this order of magnitude that was later available at VEPRO.

According to the previously quoted article from Mandens Blad for February 1941,

VEPRO had plans to expand production to also include cartoons, but only after

the war, which at the time was apparently expected by the Germans to win. A possible

production of long cartoons did not materialize, however, because VEPRO closed

as mentioned earlier in the autumn of 1942, possibly in indirect connection

with the deteriorating relationship between the Danish civilian population and

the government on the one hand and the German occupation authorities on the

other. The relationship reached a critical climax in August 1943 with the

resignation of the Danish government. This was a direct result of the German

military state of emergency, which in practice made it impossible for the

Danish government to function. (Note 17)

The precondition for at all

hoping for funding for a film project of such dimensions, as was the case with

the feature film "Fyrtøjet", had to first have a script or a

screenplay. One of these was started as early as the summer of 1942, as Finn

Rosenberg, Peter Toubro and Henning Pade met with Allan Johnsen almost daily,

either at his office, Frederiksberggade 10, or at home in Johnsen's private

home in Klampenborg.

Of the persons mentioned, Finn Rosenberg

acted as artistic consultant and supervisor, in modern parlance called art

director. Peter Toubro was given the task of being primarily responsible for

the design of the screenplay, in the broadest possible accordance with H.C.

Andersen's intentions. Henning Pade participated as a literary consultant, also

with special knowledge of H.C. Andersen's literature and time, while Allan

Johnsen was automatically given the role of financial, financial and

administrative responsible for the project's practical implementation. He was

also the only member of the team who had the personal authority and authority

to act as the day-to-day manager of the project. As recently as 1985, Henning

Pade can tell about this:

"[…] It was a - a little

too - exciting time, back then. No Danish film has a more motley (and spooky)

origin story. There were problems and difficulties on all joints and edges:

with the financing, recruitment of employees, procurement of working materials

(raw films, colors, etc. plus, of course, some useful stuff). I am pleased with

the correction you are giving Stegelmann with regard to the manuscript work,

because a great deal of work was put into it. […] ” (Henning Pade in a letter

dated New Year 1985 to Harry Rasmussen).

In a letter dated January 29,

1985, Henning Pade could, among other things, add the following:

”Thank you for your letter (dated January

10) with such a rich description of incidents and things and cases in

Frederiksberggade 10 (and 28) THEN with the FIREWORKS. It is moving to be

reminded of all that much of which is remembered exactly as you narrate, while

other things are less clear to me now, so many years later. I really hope you

hear from Peter Toubro, he is the main witness. We were closely connected

throughout the period, but have unfortunately not had much contact with each

other in recent decades. […]

It

probably all started with the fact that we were rowing friends, Allan, Peter

Toubro and I, in Skovshoved Roklub, of which Allan was a co-founder and for

many years chairman. In 1941 we rowed around Zealand together. In the summer of

1942, Allan wrote "Fra Dyreskind til Celleuld", which I, among other

things, read proofreading, and in that context I was very often with the

illustrator, Finn Rosenberg Ammitsted. He infected Allan with the cartoon

bacillus (Allan's activities were greatly reduced during the war, and his

enterprise had to be drained in other ways), and thus the plan for

"Fyrtøjet" matured - as the first Danish all-night color cartoon.

Rosenberg, of course, had to create the visuals (he became, as you know,

especially responsible for the background drawings), and the main man on the

script and screenplay was Toubro. A series of tense "hearings" and

negotiations now followed about financing and company formation (I remember

some tough meetings with director Brøndum, Nordisk Film) quite impassable, it

all seemed for a while. But at the beginning of December (still 1942), probably

exactly on the 5th, DANSK FARVE- OG TEGNEFILM A/S was founded - with the

production of "Fyrtøjet" as the immediate purpose. No one at the time

dreamed that the realization would take so many years. […] ”

According to Henning Pade, the screenplay

for "Fyrtøjet" was written during the autumn of 1942, so that one

could partly start negotiations on financing and partly think about hiring a

qualified staff to oversee and perform the artistic and technical side of the

film's production. The most important

thing, of course, was to secure employees who were familiar with the cartoon's

technique in advance.

Above is Peter Toubro on the

left, who was mainly responsible for the design of the screenplay for the

feature film "Fyrtøjet". To the right is the literary consultant

Henning Pade, who was also involved from the very beginning of the planning of

the film until 3 September 1944, when he was suddenly arrested by the Gestapo

and put in Vester Prison until his release in May 1945. Pade was - according to

himself rightly - accused of being a member of the resistance movement, which

the Germans, however, could not prove. - Photos: The portrait of Peter Toubro

belongs to his son Michael Toubro. The photo of Henning Pade has been

reproduced in SE & HØR no. 8, 1988.

In any case, on the basis of Henning

Pade's information, it can be stated with certainty that in the summer of 1942

Allan Johnsen contacted director Holger Brøndum, Nordisk Films Kompagni A/S,

which they hoped to recruit as co-producer and distributor of "Fyrtøjet".

Dealers were Allan Johnsen, Finn Rosenberg, Peter Toubro and Henning Pade on

one side of the table, and at least Holger Brøndum on the other side of this,

and possibly also Olaf Dalsgaard-Olsen, who was director of Nordisk Films Film

distribution.

The negotiations were

primarily about financing company formation, and since the seasoned 'tycoon' in

Danish film production, Holger Brøndum, from the beginning was skeptical of the